|

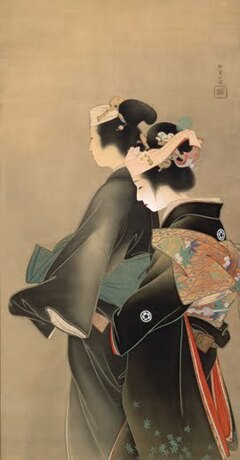

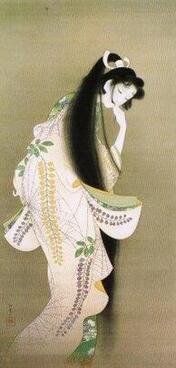

Uemura Shōen (上村 松園, April 23, 1875 – August 27, 1949) was the pseudonym of an important artist in Meiji, Taishō and early Shōwa period Japanese painting. Her real name was Uemura Tsune. Shōen was known primarily for her bijin-ga paintings of beautiful women in the nihonga style, although she produced numerous works on historical themes and traditional subjects. Shōen was born in Shimogyō-ku, Kyoto, as the second daughter of a tea merchant. She was born two months after the death of her father and, thus, grew up with her mother and aunts in an all-female household. Her mother's tea shop attracted a refined, cultured clientele for the art of Japanese tea ceremony. As a child at age 12 (1887), Shōen drew pictures and exhibited considerable skill at drawing human figures. By the age of 15 (1890) she was exhibiting her work and winning awards in official art contests as well as commissioning work for private patrons. Shōen became obsessed with the ukiyo-e, Japanese woodblock print, works of Hokusai. Her mother supported her decision to pursue an artistic career. This was quite unusual for the time, and although Shōen did have successful contemporaries who were female, such as Ito Shoba (1877-1968) and Kajiwara Hisako (1896-1988), women were largely still not part of the Japanese public art scene outside of Tokyo. Shōen is considered a major innovator in the bijin-ga genre despite the fact she often still used it to depict the traditional beauty standards of women. Bijin-ga gained criticism during the Taisho era while Shōen worked due to its lack of evolution to reflect the more modern statuses of women in Japan. During bijin-ga's conception in the Tokugawa, or Edo, period, women were regarded as lower class citizens and the genre often reflected this implication onto its female subjects. Within the Taisho era, women had made several advancements into the Japanese workforce, and artistry specifically was becoming more popular, which opened way for Shōen's success. Shōen received many awards and forms of recognition during her lifetime within Japan, being the first female recipient of the Order of Culture award, as well as being hired as the Imperial Household's official artist, which had previously only employed one other official woman in the position. In 1949 Uemura Shōen died of cancer just a year after receiving the Order of Culture Award.

0 Comments

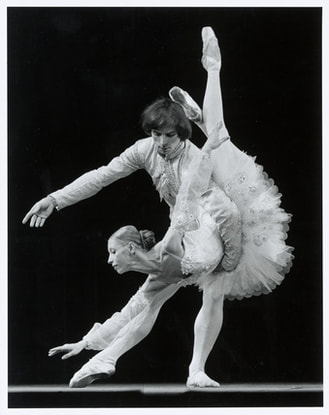

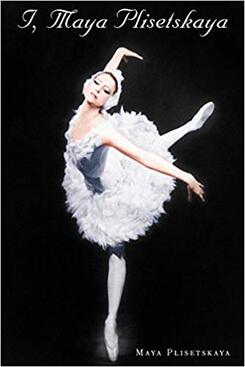

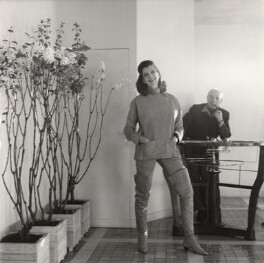

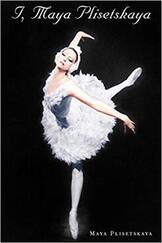

Maya Mikhailovna Plisetskaya (20 November 1925 – 2 May 2015) was a Soviet ballet dancer, choreographer, ballet director, and actress. In post-Soviet times, she held both Lithuanian and Spanish citizenship. She danced during the Soviet era at the Bolshoi Theatre under the directorships of Leonid Lavrovsky, then of Yury Grigorovich; later she moved into direct confrontation with him. In 1960 when Galina Ulanova, another famed Russian ballerina retired, Plisetskaya became prima ballerina assoluta of the company. Her early years were marked by political repression and loss. Her father Mikhail Plisetski, a Soviet official, was arrested in 1937 and executed in 1938, during the Great Purge. Her mother actress Rachel Messerer was arrested in 1938 and was imprisoned for a few years, then held in a concentration camp together with her infant son. Maya was adopted by their aunt Sulamith Messerer, principal dancers of the Bolshoi. Plisetskaya studied ballet at The Bolshoi Ballet School from age nine, and she first performed at the Bolshoi Theatre when she was eleven. She studied ballet under the direction of Elizaveta Gerdt and also her aunt, Sulamith Messerer. Graduating in 1943 at the age of eighteen, she joined the Bolshoi Ballet company, quickly rising to become their leading soloist. As a soloist, Plisetskaya created a number of leading roles, including Juliet in Lavrovsky’s Romeo and Juliet; Phrygia in Yakobson’s Spartacus (1958); in Grigorovich’s ballets: Mistress of the Copper Mountain in The Stone Flower (1959); Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty (1963); Mahmene Banu in The Legend of Love (1965); Alberto Alonso’s Carmen Suite (1967), written especially for her; and Maurice Bejart’s Isadora (1976). As an artist she had an inexhaustible interest in new roles and dance styles, and she liked to experiment on stage. Among her most acclaimed roles were Kitri in Don Quixote, Odette-Odile in Swan Lake and The Dying Swan. Her interpretation of The Dying Swan, a short showcase piece made famous by Anna Pavlova, became her calling card. Plisetskaya was known for the height of her jumps, her extremely flexible back, the technical strength of her dancing, and her charisma. She excelled both in adagio and allegro, which is very unusual in dancers. Despite her acclaim, Plisetskaya was not treated well by the Bolshoi management and she was not allowed to tour outside the country for sixteen years, concerning about her defection due to her family history. Then in 1959, Plisetskaya wrote to the Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev “a long and forthright expression of her patriotism and her indignation that it should be doubted.” and he finally decided to lift her travel ban. Since then, for the next 3 decades, with the international exposure she long deserved, Maya Plisetskaya changed the world of ballet. She set a higher standard for ballerinas, both in terms of technical brilliance and dramatic presence. After performing in Spartacus during her 1959 U.S. debut tour, Maya Plisetskaya was rated second only to Galina Ulanova by Life magazine in its issue featuring the Bolshoi. And Spartacus became a significant ballet for the Bolshoi, with one critic describing their "rage to perform", personified by Plisetskaya as ballerina, "that defined the Bolshoi." With just a few years of travelling outside Russia, Maya Plisetskaya became “an international superstar” and a continuous “box office hit throughout the world,” and she was treated by the Soviet Union as a favoured cultural emissary. Although she toured extensively during the same years that other prominent dancers defected, including Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova, and Mikhail Baryshnikov, Plisetskaya always return to Russia. Fashion designers Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Cardin considered Plisetskaya one of their inspirations, with Cardin alone having traveled to Moscow over 30 times just to see Plisetskaya perform, and she credits Cardin's costume designs for the success and recognition she received for her ballets of Anna Karenina(1974), The Seagull (1980), and Lady with the Lapdog(1985). Plisetskaya recalls Cardin's reaction when she initially suggested he design one of her costumes: "Cardin's eyes lit up like batteries. As if an electrical current passed through them." Within a week Cardin had created a design for Anna Karenina, and over the course of her career he created ten different costumes for just Karenina. Maya Plisetskaya married composer Rodion Shchedrin in 1958, who later wrote many music scores for her ballets, such as Carmen Suite created by Cuban choreographer Alberto Alonso in 1966, and later Anna Karenina(1974), The Seagull (1980), and Lady with the Lapdog(1985) seperately. In the 1980s, Plisetskaya and her husband Shchedrin spent time abroad extensively, where she worked for some of the world's most important ballet companies. In 1983–84, She was ballet director of the Rome Opera, and from 1987 to 1990, she was artistic director of Ballet del Teatro Lirico Nacional in Madrid. In 1990, Maya Plisetskaya retired as a soloist for the Bolshoi at age 65 and the next year she published her autobiography, I, Maya Plisetskaya. Beginning in 1994, she presided over the annual international ballet competition in Saint Petersburg, called Maya. In 1996 she was named the President of the Imperial Russian Ballet, Moscow private dance company and danced the Dying Swan, her signature role, at a gala in her honour in St. Petersburg. During her long and successful career, Maya Plisetskaya had won the highest awards in Soviet Union, such as the Lenin Prize and three orders of Lenin. She was also awarded many times internationally: In France, she was decorated Chevalier of the Legion of Honour and a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters, and made an honorary doctor of the Sorbonne University; In Spain, she was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts in 2005 together with the Spanish ballerina Tamara Rojo, and then awarded the Spanish Gold Medal of Fine Art. And she was also awarded in other European countries like Lithuania and Poland. In 2006, Emperor Akihito of Japan presented her with the Praemium Imperiale, informally considered a Nobel Prize for Art. Maya Plisetskaya died in Munich, Germany, on 2 May 2015 from a heart attack. Plisetskaya was survived by her husband Rodion Shchedrin, and a brother, former dancer Azari Plisetsky, a teacher of choreography at the Béjart Ballet in Lausanne, Switzerland. According to her last will and testament, she was to be cremated, and after the death of her husband, who is also to be cremated, their ashes are to be combined and spread over Russia. Further reading Books  Maya Plisetskaya, one of the world’s foremost dancers, rose to become a prima ballerina of Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet after an early life filled with tragedy and loss. In this spirited memoir, Plisetskaya reflects on her personal and professional odyssey, presenting a unique view of the life of a Soviet artist during the troubled period from the late 1930s to the 1990s. Plisetskaya recounts the execution of her father in the Great Terror and her mother’s exile to the Gulag. She describes her admission to the Bolshoi in 1943, the roles she performed there, and the endless petty harassments she endured, from both envious colleagues and Party officials. Refused permission for six years to tour with the company, Plisetskaya eventually performed all over the world, working with such noted choreographers as Roland Petit and Maurice Béjart. She recounts the tumultuous events she lived through and the fascinating people she met—among them the legendary ballet teacher Agrippina Vaganova, George Balanchine, Frank Sinatra, Rudolf Nureyev, and Dmitri Shostakovich. And she provides fascinating details about testy cocktail-party encounters with Khrushchev, tours abroad when her meager per diem allowance brought her close to starvation, and KGB plots to capitalize on her friendship with Robert Kennedy. Gifted, courageous, and brutally honest, Plisetskaya brilliantly illuminates the world of Soviet ballet during an era that encompasses both repression and cultural détente. Tim Scholl(co-author) is professor of Russian language and literature at Oberlin College. Antonina W. Bouis(translator) is the prize-winning translator of more than fifty books, including fiction, nonfiction, and memoirs by such figures as Andrei Sakharov, Elena Bonner, and Dmitri Shostakovich. "The great danger for an American woman married to a Frenchman is to become too French. To assimilate too much of another nationality weakens you. Though on the surface I might not seem to be 100 percent American, I have tried to remain as shaggy inside as possible." Biography of Pauline de Rothschild

She was born Pauline Potter at 10 rue Octave Feuillet in the Paris neighborhood of Passy, to wealthy expatriate American parents of Protestant background. Her mother was Gwendolen Cary, a great-grand-niece of Thomas Jefferson, Potter was a member of several families that were prominent in the American South since the 17th century.

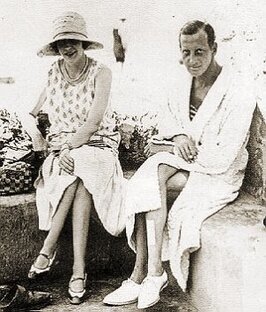

In 1930, in Baltimore, Maryland, Pauline Potter married Charles Carroll Fulton Leser (1900–1949), a grandson of one of the city's leading newspaper publishers. He was also an alcoholic and a homosexual. Soon after their marriage they moved to Majorca, Spain, but they separated in 1934, and divorced in 1939.

After she and Leser separated, Pauline Potter was romantically involved with a number of prominent men, including Paul-Henri Spaak (a Prime Minister of Belgium), American diplomat Elim O'Shaughnessy (1907-1966), French horticultural heir André Levesque de Vilmorin (1907-1987), Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovitch Romanov of Russia, and producer-director Jed Harris. For a period of years she also was the lover of Isabelle Kemp, an heiress to a New York drug-store and real-estate fortune.

In the early 1930s, Pauline Potter worked as a personal shopper in New York City, acting as a fashion advisor to wealthy socialites too busy to shop or too unsure of their personal style. Later, after moving to Spain with her first husband, Pauline operated dress shops on Majorca. She also worked for the couturier Elsa Schiaparelli in London and Paris and often was seen in society columns dressed in the firm's latest creations.

In the early 1940s, Pauline Potter and a friend, Louise Macy, a former editor of Harper's Bazaar, opened Macy-Potter, a short-lived fashion house, in New York City. The firm was bankrolled by a monetary settlement from Macy's former lover, millionaire John Hay Whitney, who had left her to marry Betsey Cushing, a former daughter-in-law of President Franklin Roosevelt. Though Macy-Potter's first (and only) collection was a critical and financial disaster, Potter went on to design a collection for Marshall Field and later to direct the custom-fashion division of Hattie Carnegie, the New York fashion company, succeeding Jean Louis, who left in 1943 to become chief fashion designer for Columbia Pictures.

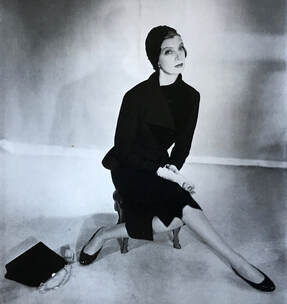

Pauline remained at Hattie Carnegie for nearly a decade and was known professionally as Mrs. Fairfax Potter. Among her clients were the Duchess of Windsor, automotive heiress Thelma Chrysler Foy, actress Gertrude Lawrence, actress Ina Claire, and prominent others. She also designed the women's costumes for John Huston's Broadway 1946 production of No Exit by Jean-Paul Sartre, starring Ruth Ford and Annabella. The gown she designed for Ford is in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

Potter also worked briefly as an uncredited fashion model. One assignment for Harper's Bazaar had her posing in the latest Grecian-style gowns for the photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe.

On 8 April 1954, Pauline Potter became the second wife of Baron Philippe de Rothschild, the owner of the fabled French winery Château Mouton Rothschild.

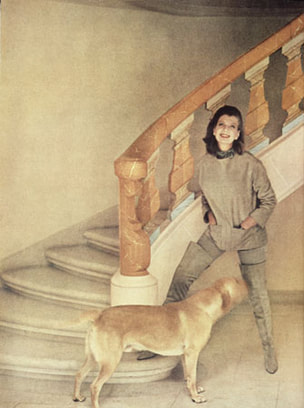

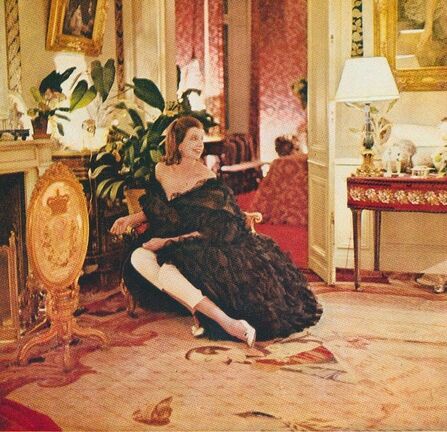

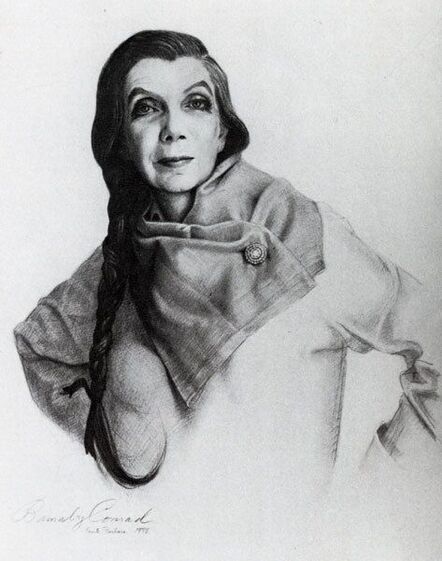

This second marriage transformed her, not only from Pauline Potter the stylish woman to Baronesse Pauline de Rothschild the style icon.

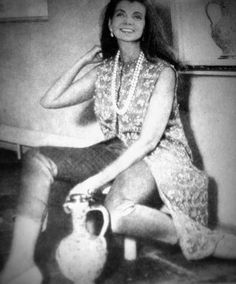

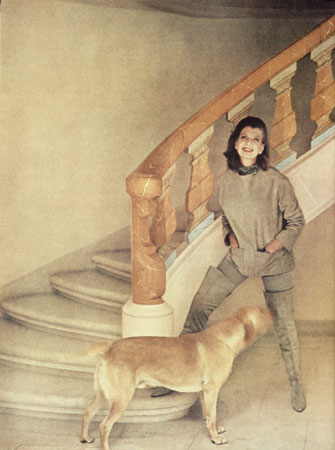

All of her early years of modelling, styling, selling and designing clothes had developed and nourished her sense of style, and now, as a Rothschild, she had the means to acquire and wrap herself in cloths of her style, the couturiers like Balenciaga, Courreges and Saint Laurent who are able to accommodate her needs, the venues to show, and the presses and photographers to immortalise "le style Pauline".

In more than a decade, she transformed herself into one of the most elegant women in the world, and in 1969, she achieved the highest honour a society lady could have: She was admitted to the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame, the only woman that year, alongside elegant men like Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Cary Grant, and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

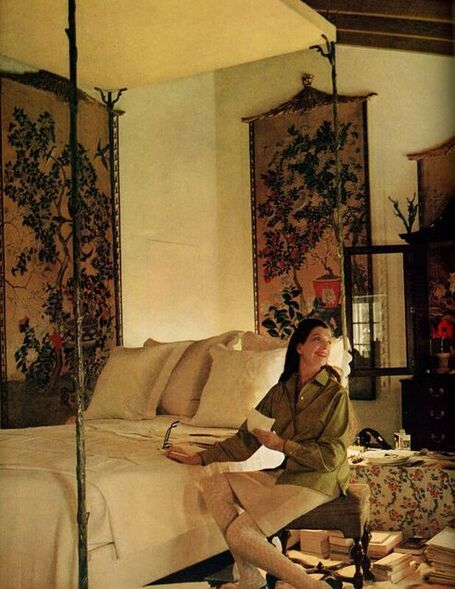

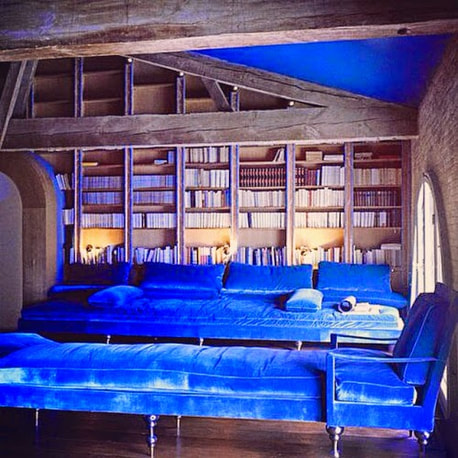

But "le style Pauline" was much more than how she dressed, or how she carried herself, it would increasingly mean the way how she decorated her houses in Paris, London, and Bordeaux, Chateau de Mouton.

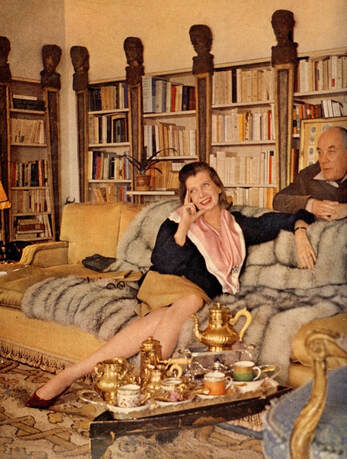

Baron Philippe de Rothschild, Pauline's second husband, a descendant of the Rothschild banking dynasty, was a race-car driver, a screenwriter, a playwright, a theatrical producer, a film producer, a poet, a wine maker, and a famed playboy. In fact, Pauline was only one of his mistresses for many years before their marriage, but after they got married, the Baron read, wrote and translated poetry with his wife, and provided her with a stage--Chateau de Mouton, for a woman of taste, energy and determination like Pauline, to act out the best role in her life.

With the help of her husband, Pauline de Rothschild renovated the war ruined estate of Rothschild in Bordeaux into one of the best wine museums in the world. A big project that took years, it showed her taste more than all the dresses she worn during those years.

If Chateau de Mouton which was designed as museum was Pauline's grand stage given to her by her husband, where family history as well as culture heritage needed needed to be considered, then their apartment in Paris and flat in London were more like her playground, like Marie Antoinette's Petit Trianon, where she can indulge much more freely her intimate and personal taste.

Pauline de Rothschild died on 8 March 1976, of a heart attack in the lobby of the Biltmore Hotel, in Santa Barbara, California. She previously had been diagnosed with breast cancer and had undergone open-heart surgery for a deteriorated valve in 1975. Rothschild's health problems were exacerbated by Marfan's syndrome, a genetic abnormality.

Further interest

Articles

Books

|

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|