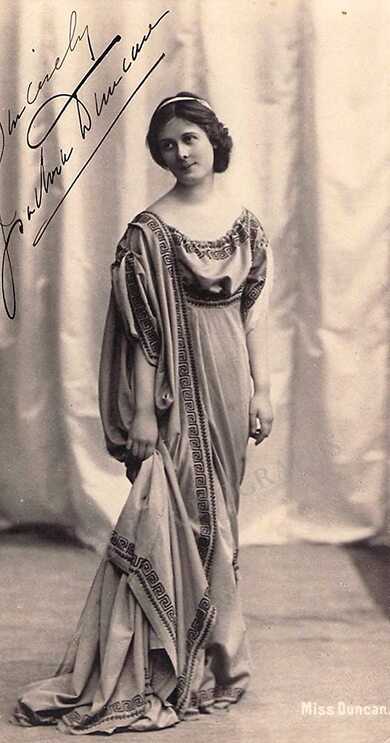

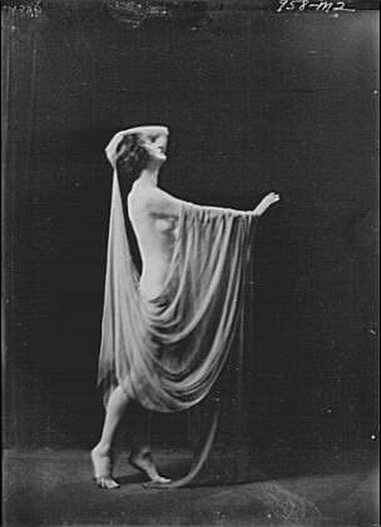

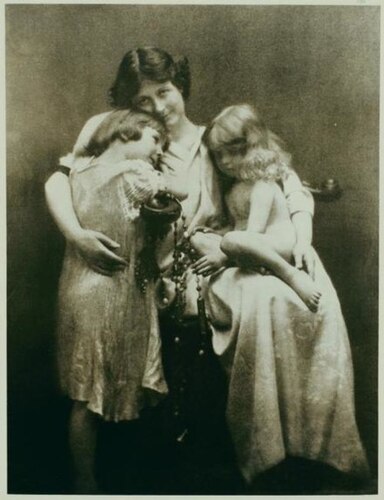

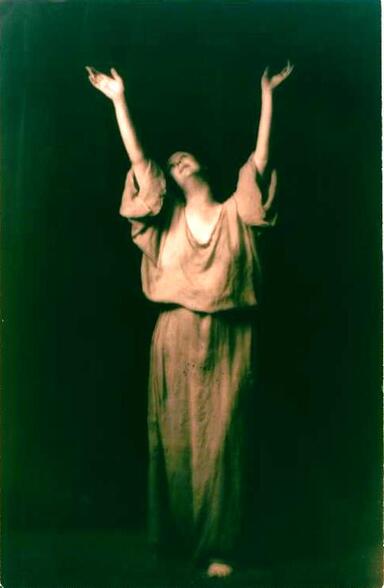

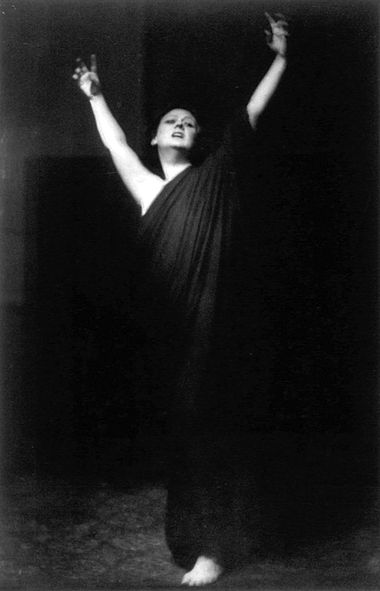

ProfileAngela Isadora Duncan (May 26, 1877 or May 27, 1878 – September 14, 1927) was an American dancer who performed to great acclaim throughout Europe. Born and raised in California, she lived and danced in Western Europe and the Soviet Union from the age of 22 until her death at age 50 when her scarf became entangled in the wheels and axle of the car in which she was travelling in Nice, France. BiographyIsadora Duncan was born in San Francisco, the youngest of the four children of Joseph Charles Duncan (1819–1898), a banker, mining engineer and connoisseur of the arts, and Mary Isadora Gray (1849–1922). She has two brothers. her sister Elizabeth Duncan, was also a dancer. Soon after Isadora's birth, Isadora's mother divorced her father and from then on, the family struggled with poverty. After her parents' divorce, Isadora's mother moved with her family to Oakland, California, where she worked as a seamstress and piano teacher. Isadora attended school from the ages of six to ten, but she dropped out, having found it constricting. She and her three siblings earned money by teaching dance to local children. Duncan's novel approach to dance had been evident since the classes she had taught as a teenager, where she "followed her fantasy and improvised, teaching any pretty thing that came into her head". A desire to travel brought her to Chicago, where she auditioned for many theater companies, finally finding a place in Augustin Daly's company. This took her to New York City in 1896 where her unique vision of dance clashed with the popular pantomimes of theater companies. While in New York, Duncan also took some classes with Marie Bonfanti but was quickly disappointed in ballet routine. Feeling unhappy and unappreciated in America, Duncan moved to London in 1898. She performed in the drawing rooms of the wealthy, taking inspiration from the Greek vases and bas-reliefs in the British Museum. The earnings from these engagements enabled her to rent a studio, allowing her to develop her work and create larger performances for the stage. From London, she traveled to Paris, where she was inspired by the Louvre and the Exposition Universelle of 1900. In France, as elsewhere, Duncan delighted her audience. In 1902, Loie Fuller invited Duncan to tour with her. This took Duncan all over Europe as she created new works using her innovative technique, which emphasized natural movement in contrast to the rigidity of traditional ballet. She spent most of the rest of her life touring Europe and the Americas in this fashion. Despite mixed reaction from critics, Duncan became quite popular for her distinctive style and inspired many visual artists, such as Antoine Bourdelle, Dame Laura Knight, Auguste Rodin, Arnold Rönnebeck, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, and Abraham Walkowitz, to create works based on her. In 1910, Duncan met the occultist Aleister Crowley at a party, an episode recounted by Crowley in his Confessions. Crowley wrote of Duncan that she "has this gift of gesture in a very high degree. Let the reader study her dancing, if possible in private than in public, and learn the superb 'unconsciousness' — which is magical consciousness — with which she suits the action to the melody." Crowley was, in fact, more attracted to Duncan's bohemian companion Mary Dempsey (a.k.a. Mary D'Este or Desti), with whom he had an affair. Desti had come to Paris in 1901 where she soon met Duncan, and the two became inseparable. Desti later wrote a memoir of her experiences with Duncan. In 1911, the French fashion designer Paul Poiret rented a mansion — Pavillon du Butard in La Celle-Saint-Cloud — and threw lavish parties, including one of the more famous grandes fêtes, La fête de Bacchus on June 20, 1912, re-creating the Bacchanalia hosted by Louis XIV at Versailles. Isadora Duncan, wearing a Greek evening gown designed by Poiret, danced on tables among 300 guests; 900 bottles of champagne were consumed until the first light of day. When the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées was built in 1913, Duncan's likeness was carved in its bas-relief over the entrance by sculptor Antoine Bourdelle and included in painted murals of the nine muses by Maurice Denis in the auditorium. Duncan disliked the commercial aspects of public performance, such as touring and contracts, because she felt they distracted her from her real mission, namely the creation of beauty and the education of the young. To achieve her mission, she opened schools to teach young women her philosophy of dance. The first was established in 1904 in Berlin-Grunewald, Germany. This institution was the birthplace of the "Isadorables" (Anna, Maria-Theresa, Irma, Liesel, Gretel, and Erika), Duncan's protégées who would continue her legacy. Duncan legally adopted all six girls in 1919, and they took her last name. After about a decade in Berlin, Duncan established a school in Paris that was shortly closed because of the outbreak of World War I. In 1914, Duncan moved to the United States and transferred her school there. A townhouse on Gramercy Park was provided for its use, and its studio was nearby, on the northeast corner of 23rd Street and Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue South). Otto Kahn, the head of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., gave Duncan use of the very modern Century Theatre at West 60th Street and Central Park West for her performances and productions, which included a staging of Oedipus Rex that involved almost all of Duncan's extended entourage and friends. During her time in New York, Duncan posed for a number of studies by the photographer Arnold Genthe. In 1921, Duncan's leftist sympathies took her to the Soviet Union, where she founded a school in Moscow. However, the Soviet government's failure to follow through on promises to support her work caused her to return to the West and leave the school to her protégée Irma. Breaking with convention, Duncan imagined she had traced dance to its roots as a sacred art. She developed from this notion a style of free and natural movements inspired by the classical Greek arts, folk dances, social dances, nature and natural forces as well as an approach to the new American athleticism. Duncan wrote of American dancing: "let them come forth with great strides, leaps and bounds, with lifted forehead and far-spread arms, to dance." Her focus on natural movement emphasized steps, such as skipping, outside of codified ballet technique. Duncan also cited the sea as an early inspiration for her movement, and she believed movement originated from the solar plexus. Duncan placed an emphasis on "evolutionary" dance motion, insisting that each movement was born from the one that preceded it, that each movement gave rise to the next, and so on in organic succession. It is this philosophy and new dance technique that garnered Duncan the title of the creator of modern dance. Duncan's philosophy of dance moved away from rigid ballet technique and towards what she perceived as natural movement. She said that in order to restore dance to a high art form instead of merely entertainment, she strove to connect emotions and movement: "I spent long days and nights in the studio seeking that dance which might be the divine expression of the human spirit through the medium of the body's movement." She believed dance was meant to encircle all that life had to offer—joy and sadness. Duncan took inspiration from ancient Greek art and combined some of its forms with a passion for freedom of movement. The Greek art has also inspired her to create her revolutionary costume of a white Greek tunic which allowed a freedom of movement that corseted ballet costumes and pointe shoes did not. In both professional and private life, Duncan flouted traditional cultural standards. She was bisexual and an atheist. Duncan bore three children, all out of wedlock. The first, Deirdre Beatrice (born September 24, 1906), by theatre designer Gordon Craig, and the second, Patrick Augustus (born May 1, 1910), by Paris Singer, one of the many sons of sewing machine magnate Isaac Singer. Her first two children drowned in the care of their nanny in 1913, when their car went into the River Seine. Following the accident, Duncan spent several months recuperating in Corfu with her brother and sister, then several weeks at the Viareggio seaside resort with the actress Eleonora Duse. In her autobiography, Duncan relates that she begged a young Italian stranger, the sculptor Romano Romanelli, to sleep with her because she was desperate for another child. She became pregnant and gave birth to a son on August 13, 1914; however, the child died shortly after birth. In 1921, after the end of the Russian Revolution, Duncan moved to Moscow where she met the poet Sergei Yesenin, who was eighteen years her junior. On May 2, 1922, they married, and Yesenin accompanied her on a tour of Europe and the United States. However, the marriage was brief, and in May 1923 Yesenin left Duncan and returned to Moscow. Two years later, on December 28, 1925, he was found dead in his room in the Hotel Angleterre in St Petersburg, in an apparent suicide. Duncan also had a relationship with the American poet and playwright Mercedes de Acosta, self-acclaimed lover of Marlene Dietrich, and sister of socialite Rita de Acosta Lydig. Their relationship was documented in numerous revealing letters they wrote to each other. In one, Duncan wrote, "Mercedes, lead me with your little strong hands and I will follow you – to the top of a mountain. To the end of the world. Wherever you wish." By the late 1920s, Duncan's performing career had dwindled, and she became as notorious for her financial woes, scandalous love life and all-too-frequent public drunkenness. She spent her final years moving between Paris and the Mediterranean, running up debts at hotels. She spent short periods in apartments rented on her behalf by a decreasing number of friends and supporters, many of whom attempted to assist her in writing an autobiography. In a reminiscent sketch, Zelda Fitzgerald wrote how she and F. Scott Fitzgerald, her husband, sat in a Paris cafe watching a somewhat drunk Duncan. He would speak of how memorable it was, but what Zelda recalled was that while all eyes were watching Duncan, Zelda was able to steal the salt and pepper shakers from the table. In his book Isadora, an Intimate Portrait, Sewell Stokes, who met Duncan in the last years of her life, describes her extravagant waywardness. Isadora Duncan's autobiography My Life was published in 1927. The Australian composer Percy Grainger called Isadora's autobiography a "life-enriching masterpiece." On the night of September 14, 1927, in Nice, France, Duncan was a passenger in an Amilcar CGSS automobile owned by Benoît Falchetto, a French-Italian mechanic. She wore a long, flowing, hand-painted silk scarf, created by the Russian-born artist Roman Chatov, a gift from her friend Mary Desti. Desti, who saw Duncan off, had asked her to wear a cape in the open-air vehicle because of the cold weather, but she would only agree to wear the scarf. As they departed, she reportedly said to Desti and some companions, "Adieu, mes amis. Je vais à la gloire !" ("Farewell, my friends. I go to glory!"); but according to the American novelist Glenway Wescott, Desti later told him that Duncan's actual parting words were, "Je vais à l'amour" ("I am off to love"). Her silk scarf, draped around her neck, became entangled around the open-spoked wheels and rear axle, pulling her from the open car and breaking her neck. Desti said she called out to warn Duncan about the scarf almost immediately after the car left. Desti brought Duncan to the hospital, where she was pronounced dead. As The New York Times noted in its obituary, "Duncan was hurled in an extraordinary manner from an open automobile in which she was riding and instantly killed by the force of her fall to the stone pavement." Other sources noted that she was almost decapitated by the sudden tightening of the scarf around her neck. At the time of her death, Duncan was a Soviet citizen. Her will was the first of a Soviet citizen's to undergo probate in the U.S. Duncan was cremated, and her ashes were placed next to those of her children in the columbarium at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. On the headstone of her grave is inscribed École du Ballet de l'Opéra de Paris ("Ballet School of the Opera of Paris"). Duncan is known as "The Mother of Dance". While her schools in Europe did not last long, Duncan's work had an impact on the art and her style is still danced based upon the instruction of Maria-Theresa Duncan, Anna Duncan, and Irma Duncan, three of her six adopted daughters. Through her sister, Elizabeth, Duncan's approach was adopted by Jarmila Jeřábková from Prague where her legacy persists. Choreographer and dancer Julia Levien was also instrumental in furthering Duncan's work through the formation of the Duncan Dance Guild in the 1950s and the establishment of the Duncan Centenary Company in 1977. Another means by which Duncan's dance techniques were carried forth was in the formation of the Isadora Duncan Heritage Society, by Mignon Garland, who had been taught dance by two of Duncan's key students. Garland was such a fan that she later lived in a building erected at the same site and address as Duncan, attached a commemorative plaque near the entrance, which is still there as of 2016. Garland also succeeded in having San Francisco rename an alley on the same block from Adelaide Place to Isadora Duncan Lane. In 1987, she was inducted into the National Museum of Dance and Hall of Fame. Further interestAudios French: Isadora Duncan (1877-1927) ou l'art de danser sa vie Isadora Duncan a été un objet de fascination totale pour ses contemporains. Venue de l’autre côté de l’océan, cette danseuse aux pieds nus, sans corset, a sidéré le public de la Belle époque par son audace, sa manière de danser, sa soif de liberté et son esprit révolutionnaire. Websites

1 Comment

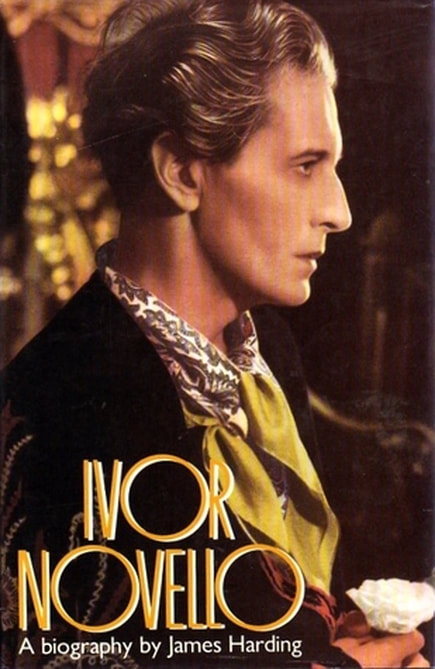

Ivor Novello (born David Ivor Davies; 15 January 1893 – 6 March 1951) was a Welsh composer and actor who became one of the most popular British entertainers of the first half of the 20th century. He was born into a musical family, and his first successes were as a songwriter. His first big hit was "Keep the Home Fires Burning" (1914), which was enormously popular during the First World War. His 1917 show, Theodore & Co, was a wartime hit. After the war, Novello contributed numbers to several successful musical comedies and was eventually commissioned to write the scores of complete shows. He wrote his musicals in the style of operetta and often composed his music to the libretti of Christopher Hassall. In the 1920s, he turned to acting, first in British films and then on stage, with considerable success in both. He starred in two silent films directed by Alfred Hitchcock, The Lodger and Downhill (both 1927). On stage, he played the title character in the first London production of Liliom (1926). Novello briefly went to Hollywood, but he soon returned to Britain, where he had more successes, especially on stage, appearing in his own lavish West End productions of musicals. The best known of these were Glamorous Night (1935) and The Dancing Years (1939). From the 1930s, he often performed with Zena Dare, writing parts for her in his works. He continued to write for film, but he had his biggest late successes with stage musicals: Perchance to Dream (1945), King's Rhapsody (1949) and Gay's the Word (1951). The Ivor Novello Awards were named after him in 1955. BiographyNovello was born David Ivor Davies in Cardiff, Wales, to David Davies (c. 1852–1931), a rent collector for the city council, and his wife, Clara Novello Davies, an internationally known singing teacher and choral conductor. As a boy, Novello was a successful singer in the Welsh Eisteddfod. His mother set up as voice teacher in London, where he met leading performers of London. Novello was educated privately in Cardiff and then in Gloucester, where he studied harmony and counterpoint with Herbert Brewer, the cathedral organist. From there he won a scholarship to Magdalen College School in Oxford, where he was a solo treble in the college choir. He later said that this prolonged youthful exposure to early sacred choral music had turned his tastes, in reaction, to lush romantic music. From his early youth Novello showed a facility for writing songs, and when he was only 15, one of his songs was published. After leaving school, he gave piano lessons in Cardiff, and then moved to London in 1913 with his mother. They took a flat above the Strand Theatre, which became his London home for the rest of his life. In London he found a mentor in Sir Edward Marsh, a well-known patron of the arts and Churchill's secretary who encouraged him to compose and introduced him to people who could help his career. He adopted his mother's middle name, "Novello", as his professional surname, although he did not change it legally until 1927. In 1914, at the start of the First World War, Novello wrote "Keep the Home Fires Burning", a song that expressed the feelings of innumerable families sundered by World War I. Novello composed the music for the song to a lyric by the American Lena Guilbert Ford, and it became a huge popular success, bringing Novello money and fame at the age of 21. He avoided enlistment until June 1916, when he reported to a Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) training depot as a probationary flight sub-lieutenant. After Novello twice crashed aeroplanes, Marsh arranged his move to the Admiralty office in central London for the rest of the war. Novello continued to write songs while serving in the RNAS. He had his first stage success with Theodore & Co in 1916. In 1917 Marsh introduced him to the actor Bobbie Andrews, who became Novello's life partner. Andrews introduced Novello to the young Noël Coward. Coward, six years Novello's junior, was deeply envious of Novello's effortless glamour. He wrote, "I just felt suddenly conscious of the long way I had to go before I could break into the magic atmosphere in which he moved and breathed with such nonchalance". In 1918 and after the war, Novello continued to write successfully for musical comedy and revue. The former included Who's Hooper? (1919), and The Golden Moth by Thompson and P. G. Wodehouse (1921), for which Novello provided the entire score. At the same time as his successes as a composer, Novello was making a career as an actor. With "a classic profile that gained him matinee idol status amongst the film-going public", he was sought out, on the strength of a publicity photograph, by the Swiss film director Louis Mercanton. Mercanton offered him a silent-film role as the romantic lead in The Call of the Blood (1920) and then in Miarka. Novello made his first British film, Carnival, the following year. Novello made his stage debut in 1921 in Deburau by Sacha Guitry, and, among other stage engagements in the next years, he played Bingley in a charity adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. At about this time, Novello had a short-lived affair with the writer Siegfried Sassoon. In 1923, Novello made his American movie debut in D. W. Griffith's The White Rose. He next co-wrote, produced and starred in the successful 1924 play The Rat. The play was made into a film in 1925, which was so successful that two sequels followed in 1926 and 1928. Other films in which Novello starred included Alfred Hitchcock's The Lodger, where he played the title character, and Downhill (both in 1927). During the late 1920s, Novello was the most popular male British film star and was often dubbed as Britain's "handsomest screen actor". The British film company Gainsborough Pictures offered Novello a lucrative contract, which enabled him to buy a country house in Littlewick Green, near Maidenhead. He renamed the property Redroofs, and he entertained there famously and with little regard for convention. Cecil Beaton, noting the frequent homosexual excesses, coined the phrase, "the Ivor – Noel naughty set". Noel Coward had by now caught Novello up professionally. In 1928 Novello starred in the silent adaptation of Coward's much more successful The Vortex, and made his last silent film, A South Sea Bubble. Novello returned to composing for the lyric stage in 1929, writing eight numbers for the revue The House that Jack Built. His successful Broadway production The Truth Game brought him to the attention of Hollywood studios. He accepted a contract to write for and appear in MGM films. He found little to do in Hollywood, however, and returned to London. After beginning the 1930s with a series of non-musical plays, Novello returned to composition in 1935 with Glamorous Night, which was the first of a series of enormously popular musicals. The Times considered that it was for these that Novello would be popularly remembered. The last of Novello's prewar musicals was The Dancing Years, which closed on the outbreak of the Second World War, and reopened at the Adelphi Theatre, running for a combined total of 696 performances, closing on 8 July 1944. This show was the closest Novello came to fulfilling his mother's early ambitions for him to write operas. Novello presented only two new shows during the Second World War. Arc de Triomphe (1943), was only a modest success, but Perchance to Dream (1945) was immensely successful, running for 1,022 performances. In between the two shows, Novello had been in serious legal trouble and served four weeks in prison for misuse of petrol coupons, a serious offence under rationing laws in wartime Britain. Novello's last full-scale production in this style was King's Rhapsody (1949). After the rigours of war, this escapist entertainment starring Novello and Zena Dare had strong box-office appeal, and ran for 841 performances. It was still running, at the Palace Theatre, when Novello's last show Gay's the Word (1951) opened. It was a departure from his established pattern, balancing the contrasting styles of European operetta and post-war American musicals. Novello died suddenly from a coronary thrombosis at the age of 58, a few hours after completing a performance of King's Rhapsody. He was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium, and his ashes are buried beneath a lilac bush and marked with a plaque that reads "Ivor Novello 6th March 1951 'Till you are home once more'." He left an estate worth £160,000 (£5 million in 2019).

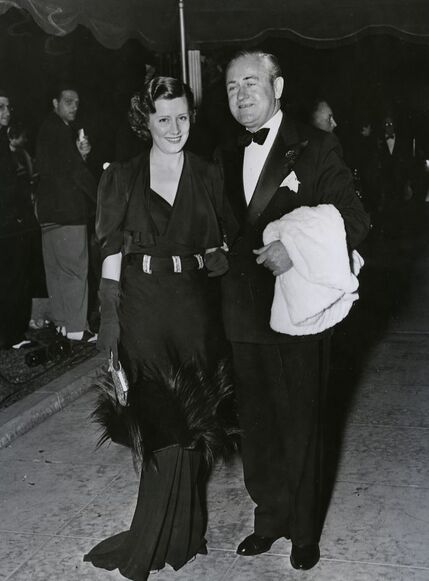

Only a few weeks before Novello's death, Noel Coward had written of him: "Theatre – good, bad and indifferent – is the love of his life. For him, other human endeavours are mere shadows. ... The reward of his work lies in the indisputable fact that whenever and wherever he appears the vast majority of the British public flock to see him." The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians writes of Novello that he was "until the advent of Andrew Lloyd Webber, the 20th-century's most consistently successful composer of British musicals". The Ivor Novello Awards for songwriting, established in 1955 in Novello's memory, are awarded each year by the The Ivors Academy to British songwriters and composers as well as to an outstanding international music writer. Ivor Novello was portrayed in Robert Altman's 2001 film Gosford Park by Jeremy Northam, and several of his songs were used for the film's soundtrack. In 2005, the Strand Theatre, above which Novello lived for many years, was renamed the Novello Theatre, with a plaque in his honour set at the entrance. Profile of Irene DunneIrene Dunne DHS (born Irene Marie Dunn) was an American actress and singer who appeared in films during the Golden Age of Hollywood. She is best known for her comedic roles, though she performed in films of other genres. She starred in 42 movies and in popular anthology television, and made guest appearances on radio until 1962; she was nominated five times for the Academy Award for Best Actress—for her performances in Cimarron (1931), Theodora Goes Wild (1936), The Awful Truth (1937), Love Affair (1939), and I Remember Mama (1948)—and was one of the top 25 highest-paid actors of her time. Irene Dunne is considered one of the best actresses who never won an Academy Award and one of the best comedic actresses in the screwball genre. She was nicknamed "The First Lady of Hollywood" for her regal manner despite being proud of her Irish-American, country-girl roots. Dunne devoted her retirement to philanthropy and was chosen by President Dwight D. Eisenhower as a delegate for the United States to the United Nations, in which she advocated for world peace and highlighted refugee-relief programs. She received numerous awards for her philanthropy, including honorary doctorates, a Laetare Medal from the University of Notre Dame, and a papal knighthood—Dame of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre. In 1985, she was awarded a Kennedy Center Honor for her services to the arts. Biography of Irene DunneIrene Marie Dunn was born on December 20, 1898 in Louisville, Kentucky. Her mother a concert pianist/music teacher of German descent taught her to play the piano as a very small girl—according to Dunne, "Music was as natural as breathing in our house". After her father, an engineer, died when she was 14, Dunne's family relocated from Kentucky to Indians, but saved all of his letters. She cherished the memories of her father all her life. She used to say, "No triumph of either my stage or screen career has ever rivalled the excitement of trips down the Mississippi on the riverboats with my father." She would also remember and live by what he told her the night before he died: "Happiness is never an accident. It is the prize we get when we choose wisely from life's great stores." Irene Dunne's first school production of A Midsummer Night's Dream began her interest in drama, so she took singing lessons as well, and sang in local churches and high school plays before her graduation in 1916. In 1920, while still second year student in Chicago Musical College, she relocated to New York hoping to become a soprano opera singer but failed two auditions with the Metropolitan Opera Company. Dunne took more singing lessons and then dancing lessons to prepare for a possible career in musical theater, eventually she starred as the leading role in the popular play Irene, which toured major cities as a roadshow throughout 1921. For the next few years Irene Dunne continued playing musical on Broadway until she was scouted by RKO. In 1924 at a supper party in New York, Dunne met Francis Griffin, a dentist and they married in Manhattan on July 13, 1927. In 1930, Irene Dunne made her Hollywood film debut in the musical Leathernecking. Already in her 30s when she made her first film, she would be in competition with younger actresses for roles, and found it advantageous to evade questions that would reveal her age, so publicists encouraged the belief that she was born in 1901 or 1904. The "Hollywood musical" era had fizzled out, so Dunne moved to dramatic roles during the Pre-Code era, leading a successful campaign for the role of Sabra in Cimarron (1931) winning her first Best Actress nomination. After Dunne's RKO contract expired she decided to become a freelance actor, and shortly after received her second Best Actress Oscar nomination for her performance in Theodora Goes Wild (1936), her first comedy role. In 1937, Irene Dunne starred in film The Awful Truth (1937), the first of three films she played opposite Cary Grant, with the other two being My Favorite Wife (1940) and Penny Serenade (1941). Dunne also starred in three films with Charles Boyer: Love Affair (1939), When Tomorrow Comes (1939), and Together Again (1944). Dunne and Grant were praised as one of the best romantic comedy couples, while the Dunne and Boyer pairing was praised as the most romantic in Hollywood. Nicknamed “The First Lady of Hollywood”, Irene Dunne’s fashion tastes were often the talk of newspapers and Best Dressed lists featured her as one of the most stylist celebrities in the world. Irene Dunne explained in a 1939 fashion-advice interview that her husband was partially responsible because he was equally stylish, but also chooses outfits based on personality, color scheme and the context of where the outfits will be worn. McCall's magazine later revealed Dunne chose outfits specifically designed for her by Mainbocher and Jean Louis because she did not like buying clothes in stores. The comedy It Grows on Trees(1952) was Dunne's last movie performance, and her last acting credit was in 1962. In her retirement, Irene Dunne devoted herself primarily to humanitarianism. In 1957, President Eisenhower appointed Dunne one of five alternative U.S. delegates to the United Nations in recognition of her interest in international affairs and Roman Catholic and Republican causes. Dunne died at the age of 91 in her Holmby Hills home on September 4, 1990 after bed riden for a month.

|

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|