|

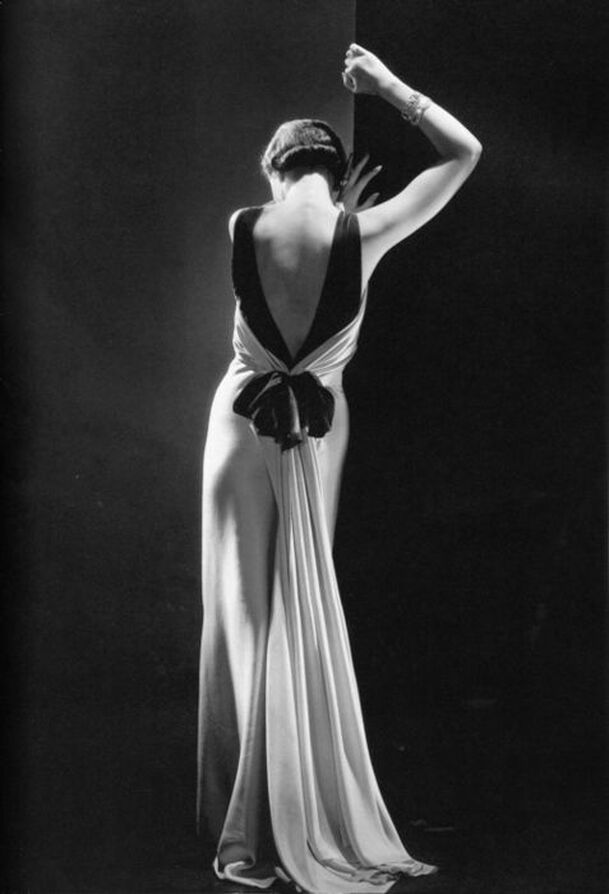

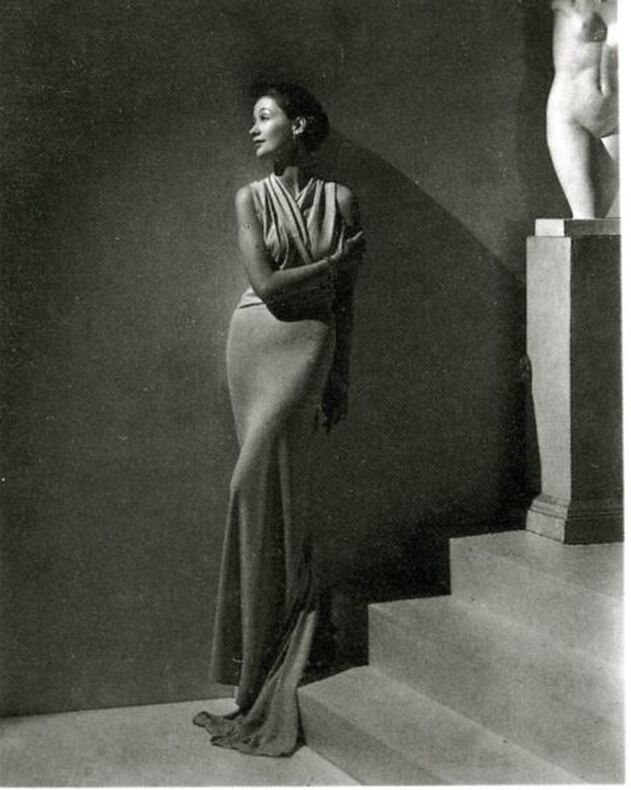

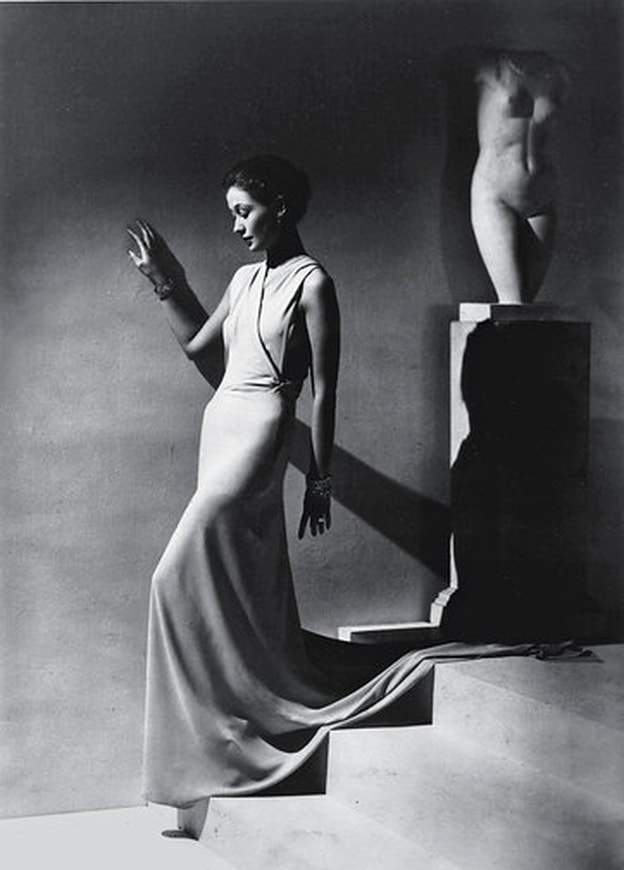

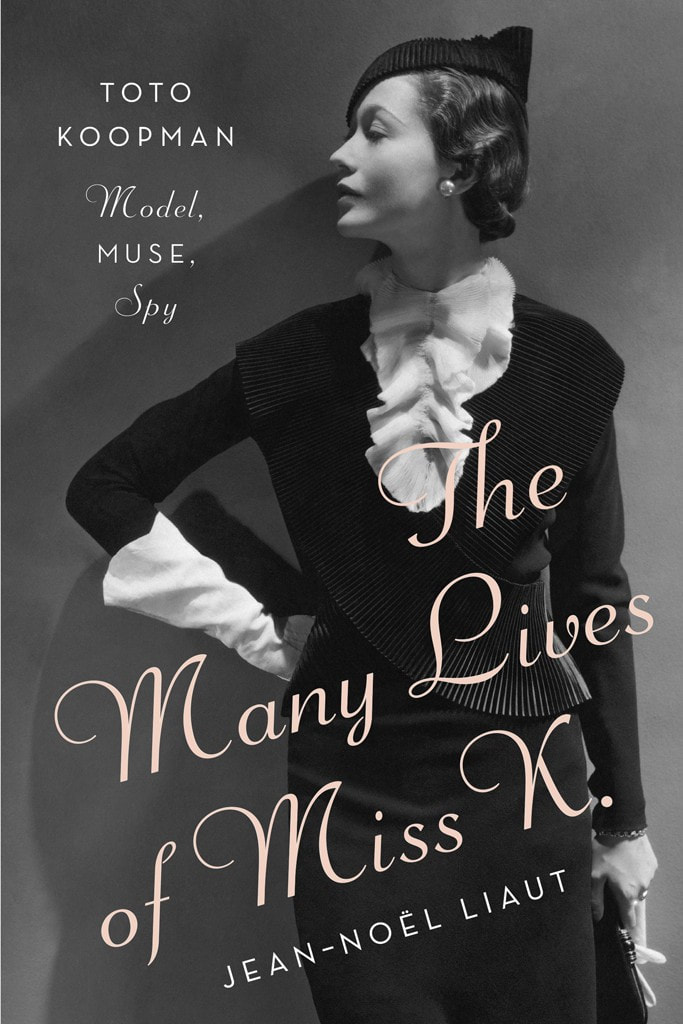

Catharina "Toto" Koopman (28 October 1908 – 27 August 1991) was a Dutch-Javanese model who worked in Paris prior to World War II. During that war she served as a spy for the Italian Resistance and was captured and held prisoner in the Ravensbrück concentration camp. She later helped establish the Hanover Gallery as one of the most influential art galleries in Europe in the 1950s. BiographyBorn in Java in 1908, Catharina Koopman was the daughter of the Dutch cavalry officer Jan George Koopman and Catharina Johanna Westrik, of Dutch and Javanese descent. She was named Catharina, but came to prefer Toto, her childhood nickname after her father's favourite horse. Her only sibling, Henry, nicknamed Ody Koopman (1902–1949), became a successful tennis player. Toto Koopman left Java in 1920 to attend a boarding school in the Netherlands where she developed a talent for languages and became fluent in English, French, German and Italian. After a year at an English finishing school, she moved to Paris to work as a model. In Paris, Koopman worked as a house model for Coco Chanel but quit after only six months. She also worked for the designers Rochas, Mainbocher and Madeleine Vionnet, appeared regularly in Vogue Paris and was photographed by Edward Steichen, Cecil Beaton, Horst P. Horst and George Hoyningen-Huene. Her most famous photo, was one that taken by George Hoymingen-Huene with her modeling an Augusta Bernard evening dress with very low back. Koopman had a small part in the film The Private Life of Don Juan and although this was cut from the final production she still attended the film's premiere with Tallulah Bankhead, who introduced her to Max Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook, generally known as Lord Beaverbrook. Although Lord Beaverbrook was thirty years older than Koopman, the two began, in 1934, an affair that lasted some years. He was happy to pay for her travels throughout Europe in the 1930s and she often attended opera performances in Germany and Italy. When Beaverbrook discovered that Koopman was also in a relationship with his son, Max Aitken, he ran a series of stories in the newspapers he owned, including the Daily Express and the London Evening Standard, that made Koopman an outcast in London high-society. Koopman and the younger Aitken lived together for four years but he ended the relationship when she refused to marry him. In fact Koopman had signed an agreement with Beaverbrook which granted her a pension for life from him provided she did not marry his son. In 1939 Toto Koopman left London to live in Italy. There she began a relationship with a leader of the anti-Mussolini resistance. When World War II broke out, she agreed to use her contacts and language skills to spy for the Italian Resistance. She infiltrated meetings of the Black Shirts but was captured. After spells in prisons in Milan and Lazio she was sent to the Massa Martina detention camp but escaped and hid in the mountains around Perugia, where she worked with a local resistance group. She was recaptured, promptly escaped again, and made her way to Venice. There, in October 1944, Koopman was caught spying on high-ranking German officers in the Danieli Hotel and quickly deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Very shortly before the camp was liberated in April 1945, the Nazi authorities released several hundred prisoners, including Koopman, to the care of the Red Cross in Sweden. Randolph Churchill, the son of Winston Churchill, one of Toto Koopman's former boyfriends, went to Gothenburg and helped the emaciated Koopman obtain new clothes, a new passport and a wig for her shaved head. While recuperating in Ascona in 1945, Koopman met the art dealer Erica Brausen who would become the love of her life. The two became lovers and would remain together for the rest of their lives. Brausen wanted to open her own commercial gallery in London, so Koopman helped her. They went to London and opened theHanover Gallery. There they hosted shows by the then still new artists like Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Marel Duchamp and Henry Moore, in particular Francis Bacon, with whom Brausen was obssessed. In due course the Hanover Gallery became one of the most influential galleries in Europe, which was noted both for the artists it featured and the unusual two women who owned it. During the 1950s Koopman studied at the University of London and took part in several archaeological excavations. She made a donation of books to the Institute of Archaeology in London. In 1959 Koopman and Brausen bought a property on the island of Panarea where they built six villas amongst extensive gardens and entertained very lavishly. The two women continued to live together until Toto Koopman's death in August 1991. Erica Brausen "locked herself in a room with the body for 8 days, emerging only to buy fresh roses that she would arrange around Koopman's face every morning". 18 months later, Erica Brausen followed her to the tomb. Further interestBooks

0 Comments

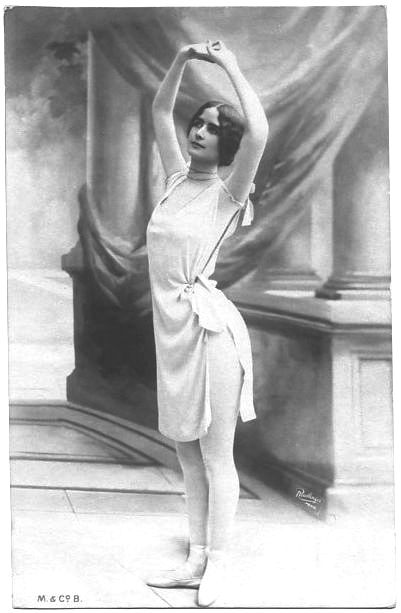

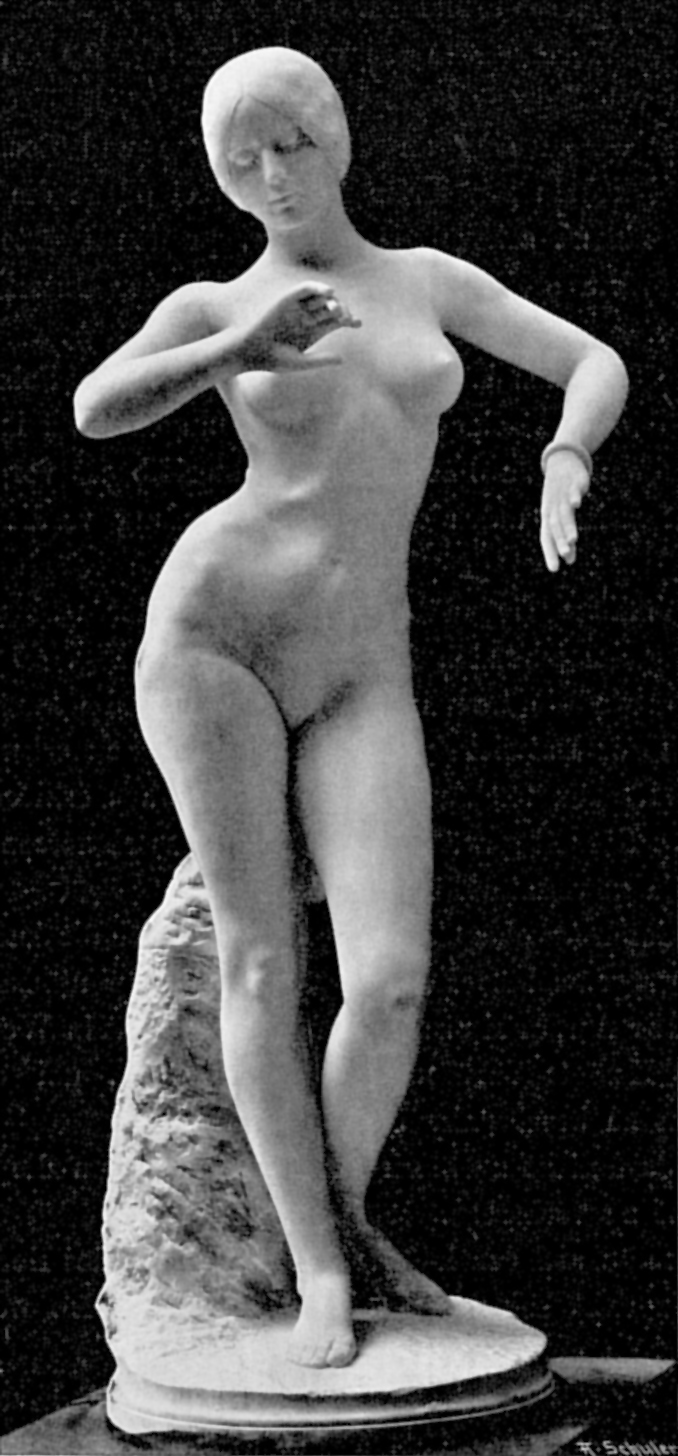

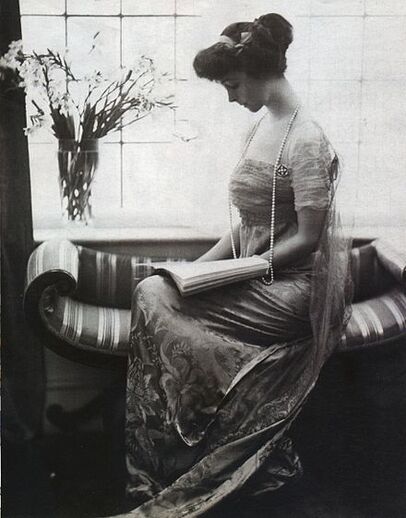

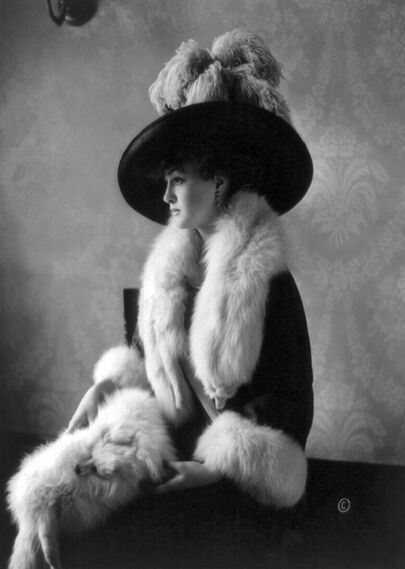

Cléopâtre-Diane de Merode, known as Cléo de Mérode, is a dancer, model and beauty icon of France. She was born on 27 September 1875 in Paris and died on 17 October 1966 in the same city. Cléopâtre-Diane de Merode, dite Cléo de Mérode, est une danseuse, modèle et icône de beauté française née le 27 septembre 1875 dans le 5e arrondissement de Paris et morte le 17 octobre 1966 dans le 8e arrondissement de la même ville. BiographyCléopâtre-Diane de Merode was born in Paris, France on 27 September 1875, as the illegitimate daughter of Vincentia Marie Cécilia von Merode (1850-1899), a Belgian baroness and her lover, an upper class Austrian. Although Vincentia de Merode was abandoned by her lover, her family provided her and her daughter with financial support, and Cléopâtre-Diane de Merode studied in the convent of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul in Paris, then trained at the dance school of Opéra de Paris. In 1896, Cléopâtre-Diane, by then called Cléo de Mérode, created a ballet in the casino of Royan by French composer Louis Ganne Phryné, which later became an important piece in Opéra de Paris. She also danced in other ballets created by different composers, such as Coppélia, Sylvia ou la Nymphe de Diane by Léo Delibes, Les Deux Pigeons by André Messager, L'Étoile by André Wormser and Le Couronnement de la Muse by Gustave Charpentier. In 1898 Cléo de Mérode left Opéra de Paris and since then embarked on her career as an independent dancer and sometimes choreographer, until the breakout of The First World War. In 1900, she produced and danced in the ballet danses cambodgiennes, at the Universal Exposition in Paris; In 1902, she created Tanagra inspired by the poem of same name by Paul Franck, as well as another ballet Phoébé. In 1901, the director of Folies Bergère, Édouard Marchand, hired her to dance in a three act ballet pantomime Lorenza, his last creation in Paris. Cléo de Mérode retired from her dancing career 1924, and since then, had only danced occasionally. Although a successful dance of her epoque, Cléo de Mérode was known by her extraordinary beauty. She was courted by countless men, many of them famous, including King Léopold II of the Belgians. Various artists of her time were also inspired by her beauty, and she had posed for the sculptor Alexandre Falguière, the painters Edgar Degas, Jean-Louis Forain, Giovanni Boldini, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, etc. Some of the artists, like Paul Klee, as well as the writers of the time, such as Jean de Tinan, Georges Rodenbach, also left written testimonial expressing their fascination of the beauty and grace of Cléo de Mérode. French writer Jean Cocteau wrote that she was « la Belle des belles »(The Beauty of the beauties). And thanks to the photographers of her époque, in particular Léopold-Émile Reutlinger (1863-1937), who was mesmerized by her delicate beauty, Cléo de Mérode's image was diffused internationally, making her one of the first women well known around the world. In 1896, Cléo de Mérode was elected “Beauty Queen” by the readers of The Paris magazine L'Illustration based on the photos. The Magazine had presented to their reader 131 celebrities, including Sarah Bernhardt for them to choose from. And that same year, Cléo de Mérode became more notorious when French sculptor Alexandre Falguière presented his nude sculpture of the dancer titled La Danseuse at the Salon des artistes français. Cléo de Mérode defended her honor acclaiming that she had never posed for the sculptor naked and accused Alexandre Falguière using her head together with the body of another model. But hard as she tried defending herself, Cléo de Mérode's fame was tinted, worsened by the rumor that she was the lover of King Léopold II of the Belgians. And she would have to fight for her reputation for the rest of her life. In 1949, the French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir mentioned Cléo de Mérode as a "Cocotte"(a woman of certain reputation) in her book Le Deuxième Sexe (The Second Sex). Cléo de Mérode filed a lawsuit against the philosopher reclaiming millions of francs. She won the lawsuit the second year with a symbolic one franc. But her reputation was not completed saved. Even as late as 2015, long after her death, Cléo de Mérode was included in an exposition of the prostitution of Belle Époque at musée d'Orsay. In 1955, she published her autobiography, titled Le Ballet de ma vie(The Ballet of My Life), in which she revealed her real relations with King Léopold II of the Belgians. Cléo de Mérode died on 17 October 1966 at her home in Paris, at the age of 91. BiographieIssue d'une naissance illégitime, elle est la fille naturelle de Vincentia Marie Cécilia von Merode (1850-1899), baronne belge issue de la branche autrichienne de la famille de Merode, abandonnée par son amant, membre de la haute bourgeoisie autrichienne. Vincentia de Merode conserve toutefois le soutien financier de sa famille. Sa fille étudie chez les sœurs de Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, rue de Monceau à Paris. Formée à l'école de danse de l'Opéra de Paris, Cléopâtre-Diane, dite Cléo de Mérode, crée en 1896 au casino de Royan Phryné, un ballet de Louis Ganne, puis est nommée grand sujet à l'Opéra de Paris et danse dans Coppélia, Sylvia ou la Nymphe de Diane de Léo Delibes, Les Deux Pigeons d'André Messager, L'Étoile d'André Wormser et Le Couronnement de la Muse de Gustave Charpentier. Elle quitte l'institution en 1898 puis entreprend une carrière indépendante internationale et danse jusqu'à la Première Guerre mondiale. Son charme lui vaut alors une foule d'admirateurs intéressés. Elle se produit à l'Exposition universelle de Paris en 1900 dans les « danses cambodgiennes », crée en 1902 à Moscou et Madrid Tanagra sur un poème de Paul Franck puis Phoébé à l'Opéra-Comique à Paris. En 1901, le directeur des Folies Bergère, Édouard Marchand, la recrute pour un ballet pantomime en trois actes dénommé Lorenza. C’est le dernier grand spectacle qu'il organise dans cette salle parisienne. Malgré une rentrée réussie en 1924, elle décide de se retirer du monde de la danse à Paris. Sur la demande d'Henri Varna et Émile Audiffred, elle reparaît ponctuellement sur scène en juin 1934 dans La revue 1900 aux côtés du danseur George Skibine. « Je portais une robe de satin rose, baleinée à la taille, très longue, avec un ruché dans le bas. Nous dansions cinq valses à la file ; nous finissions par un grand tourbillon, et Skibine m'emportait dans ses bras au fond de la scène ». Sa beauté délicate, hors des canons de beauté 1900, est restée légendaire, ainsi que les hommages qu'elle reçoit de quelques célèbres soupirants, plus particulièrement le roi Léopold II de Belgique, aventures qu'elle relate dans ses mémoires, Le Ballet de ma vie, publiées en 1955 par les Éditions Horay, à Paris. La rumeur infondée de leur liaison et, par conséquent de son influence sur la politique belge et congolaise, a cependant nui à sa réputation. Elle pose pour le sculpteur Alexandre Falguière, pour les peintres Edgar Degas, Jean-Louis Forain, Giovanni Boldini, elle est représentée par Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, par le verrier capitaine d’industries et artiste Georges Despret, et a son effigie en cire au musée Grévin dès 1895, façonnée par le chef d'atelier du musée, le sculpteur Léopold Bernstamm. Elle est une des premières femmes dont l’image photographique, due notamment aux photographes Paul Nadar (1856-1939), fils et successeur de Félix Nadar, et surtout Léopold-Émile Reutlinger (1863-1937), est diffusée à l'échelle mondiale. Elle pose également pour l'atelier photographique Benque (photographies prises à l'Opéra de Paris, à partir de 1890), le photographe Charles-Pierre Ogerau (1868-1908), auteur d'une série de portraits en 1895, et plus tard, Henri Manuel (1874-1947). Élue « reine de Beauté » sur photographies par les lecteurs de L'Illustration en 1896, parmi 131 célébrités, dont Sarah Bernhardt ; elle accroît sa notoriété la même année avec un parfum de scandale, du fait de l'exposition de la sculpture La Danseuse d’Alexandre Falguière au Salon des artistes français. Ce nu en marbre blanc grandeur nature aurait été taillé d'après un moulage en plâtre de son corps, œuvre conservée à Paris au musée d'Orsay. Si le grain de la peau visible sur le plâtre prouve bien un moulage sur le vif, Cléo de Mérode s'est pourtant toujours défendue d'avoir posé nue. Elle accuse Falguière d’avoir fabriqué une œuvre à scandale en moulant le corps de la statue sur un autre modèle féminin, alors qu’elle n’aurait posé que pour la tête. Des personnalités contemporaines aussi diverses que les hommes de lettres Jean de Tinan, Georges Rodenbach, ou le peintre Paul Klee, laissent des témoignages écrits exprimant le pouvoir de fascination qu'exerçait son image, en mouvement sur scène, ou fixée par la photographie. Jean Cocteau écrit qu'elle est « la Belle des belles », « cette vierge qui ne l'est pas, cette dame préraphaélite qui marche les yeux baissés à travers les groupes. […] Un autre fantôme l'escorte, un fantôme royal avec un bel éventail de barbe blanche. Le profil de Cléo est tellement gracieux, tellement divin que les caricaturistes s'y brisent ». Le poète fait ici référence à sa liaison supposée mais toujours démentie par elle avec le roi des Belges Léopold II. En 1950, Cléo de Mérode gagne un procès contre Simone de Beauvoir, qui en 1949 dans Le Deuxième Sexe l'assimilait à une « cocotte », ignorant par ailleurs qu'elle était encore en vie. Le juge considère que l'ancienne danseuse aurait dû publiquement démentir cette rumeur à l'époque mais indique que les propos de la philosophe sont inconvenants et la condamne à faire retirer cette mention de son livre et à un franc symbolique d'amende, alors que Cléo de Mérode réclamait millions. Dans Les femmes, actrices de l'Histoire, l'historienne Yannick Ripa écrit : « Réputée pour sa grande beauté, plus encore que pour ses talents de danseuse, Cléo de Mérode luttera toute sa vie contre sa réputation de demi-mondaine ». La même réputation lui est donnée lors d'une exposition sur la prostitution de la Belle Époque en 2015 au musée d'Orsay. Pendant l’Occupation, elle se retire à Saint-Gaultier, dans l’Indre. Elle retourne ensuite vivre à Paris. Elle séjourne plusieurs étés de sa vie à Biarritz ou au château de Rastignac à La Bachellerie en Dordogne, chez la famille Lauwick. En 1955, elle publie son autobiographie, intitulée Le Ballet de ma vie. Elle meurt à l'âge de 91 ans le 17 octobre 1966, à son domicile parisien situé au 15, rue de Téhéran (8e arrondissement de Paris). Cléo de Mérode est inhumée aux côtés de sa mère Vicentia (Cense de Merode) au cimetière du Père-Lachaise (90e division). Une statue la représentant, sculptée en 1909 par le diplomate et sculpteur espagnol Luis de Périnat, qui fut son amant de 1906 à 1919 — mais qu'elle avait quitté à la suite de son infidélité —, orne leur tombe. Further interestAudio

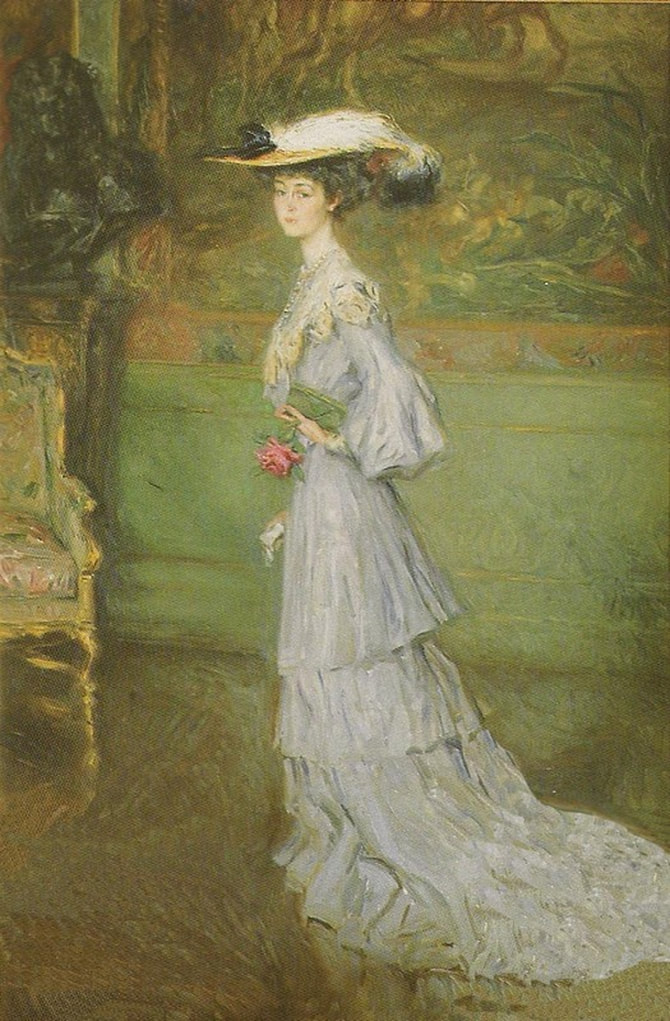

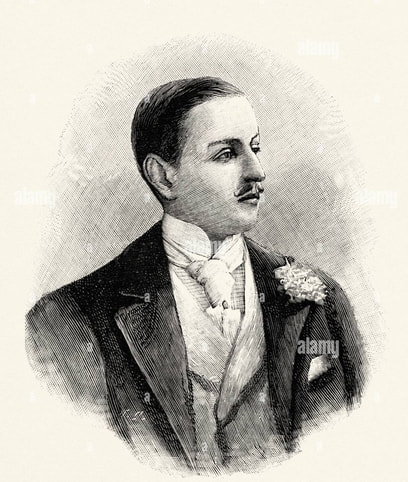

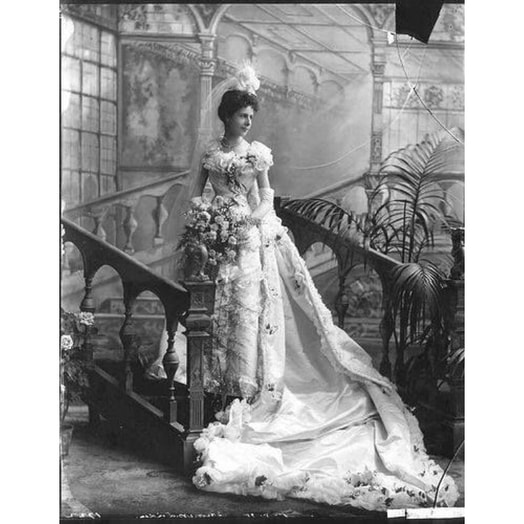

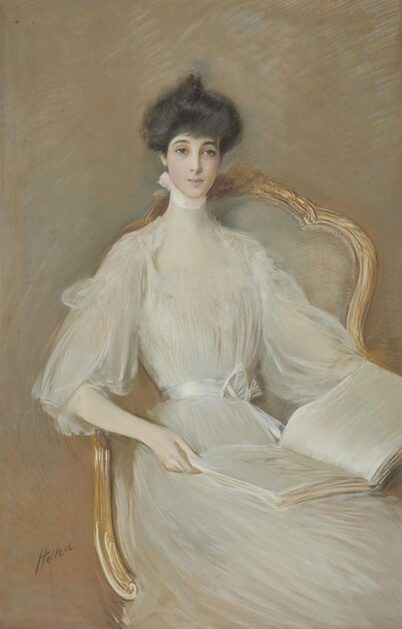

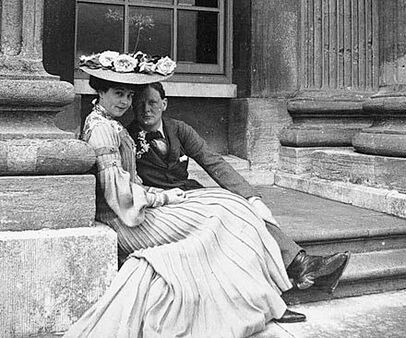

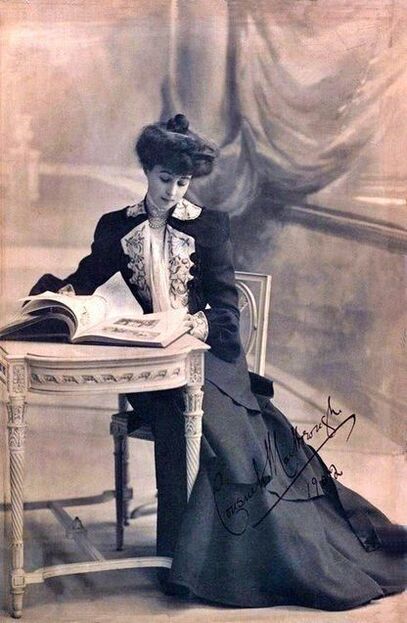

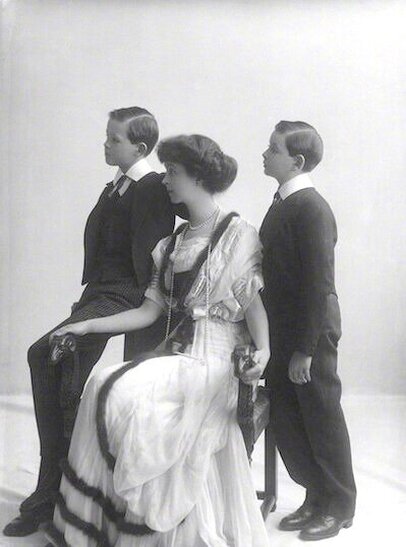

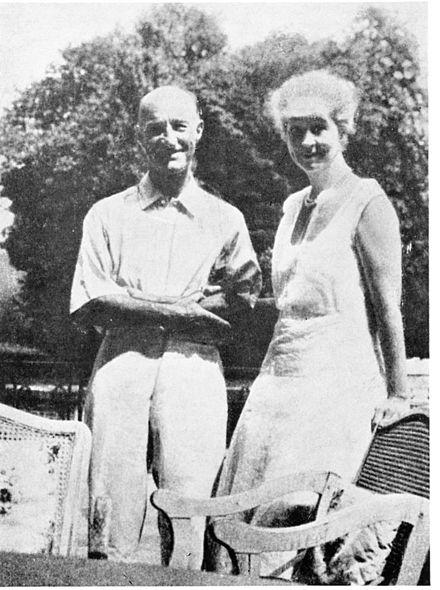

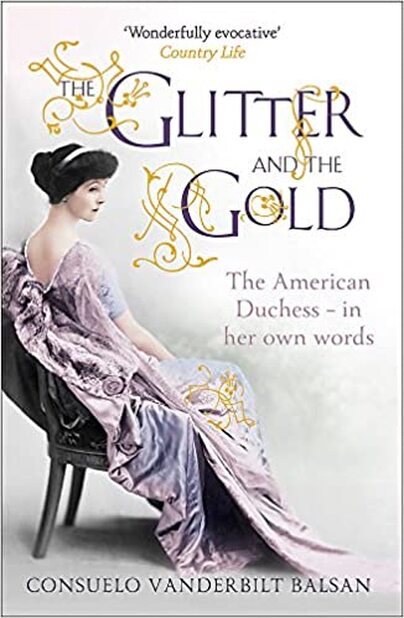

Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan (formerly Consuelo Spencer-Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough; born Consuelo Vanderbilt; 2 March 1877 – 6 December 1964) was a member of the prominent American Vanderbilt family. Her first marriage to the ninth Duke of Marlborough has become a well-known example of one of the advantageous, but loveless, marriages common during the Gilded Age. The Duke obtained a large dowry by the marriage, and reportedly told her just after the marriage that he married her in order to "save Blenheim" Palace, his ancestral home. Consuelo Vanderbilt and her friends were the inspiration for Edith Wharton's unfinished novel The Buccaneers. Although the teenage Consuelo was opposed to the marriage arranged by her mother, she became a popular and influential Duchess. For much of the marriage, the Marlboroughs lived separately and the marriage was finally annulled. She went on to marry a wealthy French aviator and continued her charitable endeavours. BiographyBorn in New York City, Consuelo Vanderbilt was the only daughter and eldest child of William Kissam Vanderbilt, a New York railroad millionaire, and his first wife, a Southern belle Alva Erskine Smith (1853–1933, who later married Oliver Belmont) from Mobile, Alabama, the daughter of a cotton broker. Her Spanish name was in honor of her godmother, Consuelo Yznaga (1853–1909), a half-Cuban, half-American socialite who created a social stir a year earlier when she married the fortune-hunting George, Viscount Mandeville, a union of Old World aristocracy and New World money that caused the groom's father, the 7th Duke of Manchester, to openly wonder if his son and heir had married a "Red Indian". Consuelo Vanderbilt was largely dominated by her mother, who was determined that her daughter would make a great marriage like that of her famous namesake. In her autobiography, Consuelo Vanderbilt described how she was required to wear a steel rod, which ran down her spine and fastened around her waist and over her shoulders, to improve her posture. She was educated entirely at home by governesses and tutors, and learned foreign languages at an early age. Her mother was abusive and whipped her with a riding crop for minor infractions. When, as a teenager, Consuelo objected to the clothing her mother had selected for her, Alva told her that "I do the thinking, you do as you are told." Consuelo Vanderbilt was considered a great beauty, with a face compelling enough to cause the playwright Sir James Barrie, author of Peter Pan, to write, "I would stand all day in the street to see Consuelo Marlborough get into her carriage." And she attracted numerous title-bearing suitors anxious to trade social position for cash. Her mother reportedly received at least five proposals for her hand. Consuelo was allowed to consider the proposal of just one of the men, Prince Francis Joseph of Battenberg, but she developed an instant aversion to him. None of the others, however, was good enough for Alva Vanderbilt, who wasdetermined to secure the highest-ranking mate possible for her only daughter, a union that would emphasize the preeminence of the Vanderbilt family in New York society. With the help of Lady Paget, the wife of Sir Arthur Paget, and daughter of an socially ambitious widow of an American hotel entrepreneur, Alva Vanderbilt engineered a meeting between Consuelo and the indebted, titled Charles Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough, chatelain of Blenheim Palace. Lady Paget, always short of money, soon became a sort of international marital agent, introducing eligible American heiresses to British noblemen. Consuelo Vanderbilt had no interest in the duke, being secretly engaged to an American, Winthrop Rutherfurd. Her mother cajoled, wheedled, begged, and then, ultimately, ordered her daughter to marry Marlborough. When Consuelo – a docile teenager whose only notable characteristic at the time was abject obedience to her fearsome mother – made plans to elope, she was locked in her room as Alva threatened to murder Rutherfurd. Still she refused. It was only when Alva Vanderbilt claimed that her health was being seriously and irretrievably undermined by Consuelo's stubbornness and appeared to be at death's door that the malleable girl acquiesced. Alva made an astonishing recovery from her entirely phantom illness, and when the wedding took place, Consuelo stood at the altar reportedly weeping behind her veil. The duke, for his part, gave up the woman he reportedly loved back in England and collected US$2.5 million (approximately US$75.2 million in 2019 dollars) in railroad stock as a marriage settlement. His purpose of marrying her was to restore his beloved Bleinheim Palace in Oxfordshire. Consuelo Vanderbilt married Charles Spencer-Churchill, The 9th Duke of Marlborough at St. Thomas Episcopal Church, New York City, on 6 November 1895. After her marriage, Consuelo Vanderbilt's father built a mansion for her in London, Sunderland House in Curzon Street. The new Duchess of Marlborough was adored by the poor and less fortunate tenants on her husband's estate, whom she visited and to whom she provided assistance. She later became involved with other philanthropic projects and was particularly interested in those that affected mothers and children. She was also a social success with royalty and the aristocracy of Britain. Consuelo Vanderbilt gave birth to two sons, John Albert William Spencer-Churchill, Marquess of Blandford (who became 10th Duke of Marlborough) and Lord Ivor Spencer-Churchill. However, given the ill-fitting match between the duke and his wife, it was only a matter of time before their marriage was in name only. The duchess eventually was smitten with her husband's cousin, the Hon. Reginald Fellowes, while the duke fell under the spell of Gladys Marie Deacon, an eccentric American of little money but, like Consuelo, dazzling to look at and of considerable intellect. The Marlboroughs separated in 1906. Consuelo Vanderbilt and Charles Spencer-Churchill, The Duke of Marlborough divorced in 1921. Shortly afterwards, on 25 June 1921 The Duke of Marlborough married Gladys Deacon. A few days later, on 4 July 1921, Consuelo Vanderbilt married Colonel Jacques Balsan, a textile manufacturing heir and a record-breaking pioneer French balloon, aircraft, and hydroplane pilot who once worked with the Wright Brothers. Jacques Balsan was a younger brother of Etienne Balsan, who was an early lover of Coco Chanel. On 19 August 1926, the marriage of Consuelo Vanderbilt and The Duke of Marlborough was annulled, at the duke's request and with Consuelo's assent, Though largely embarked upon as a way to facilitate the Anglican duke's desire to convert to Roman Catholicism, the annulment, to the surprise of many, also was fully supported by the former duchess's mother, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, who testified that the Vanderbilt–Marlborough marriage had been an act of unmistakable coercion. In later years, Consuelo and her mother enjoyed a closer, easier relationship. After the annulment of her marriage to the Duke of Marlborough, Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan still maintained ties with favorite Churchill relatives, particularly Winston Churchill, cousin of The 9th Duke of Marlborough. He was a frequent visitor to her château, in Saint-Georges-Motel, a small commune near Dreux about 50 miles from Paris, in the 1920s and 1930s, where he completed his last painting before the war. Records in Florida show that in 1932 Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan built a home in Manalapan, Florida, just south of Palm Beach. It was designed as a love nest by Maurice Fatio. The dream home of 26,000 square feet is called Casa Alva, in honor of her mother. Although Consuelo sold her home in 1957, it still exists. The Duke of Marlborough and his new wife Gladys Deacon's marriage did not turn out to be a happy one. Gladys Deacon, famed for her Greek beauty became increasingly eccentric and evicted from Blenheim Palace. On 30 June 1934, The Duke of Marlborough died of heart attack, at age 88. Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan published her insightful but not entirely candid autobiography, The Glitter and the Gold, in 1953. It was ghostwritten by Stuart Preston, an American writer who was an art critic for The New York Times. A reviewer in the same paper called it "an ideal epitaph of the age of elegance." Jacques Balsan died in New York on 4 November 1956 at the age of 88. Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan died at Southampton, Long Island, New York, on 6 December 1964. She was buried alongside her younger son, Lord Ivor Spencer-Churchill, in the churchyard at St Martin's Church, Bladon, Oxfordshire, England, near her former home, Blenheim Palace. During World War I, Consuelo Vanderbilt worked as the chair of the Economic Relief Committee for the American Women's War Relief Fund.

During the inter-war period, she and Winaretta Singer-Polignac (the Princess de Polignac and Singer Sewing Machine heiress) worked together in the construction of a 360-bed hospital destined to provide medical care to middle class workers. The result of this effort is the Foch Hospital, located in Suresnes, a suburb of Paris, France. The hospital also includes a school of nursing and is one of the top ranked hospitals in France, especially for renal transplants. It has remained true to its origins and stayed a private not-for-profit institution that still serves the Paris community. It is managed by the Fondation médicale Franco-américaine du Mont-Valérien, commonly called Foundation Foch. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|