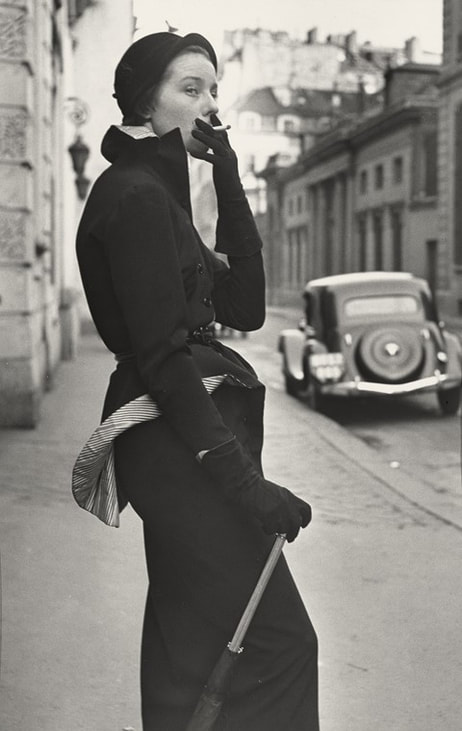

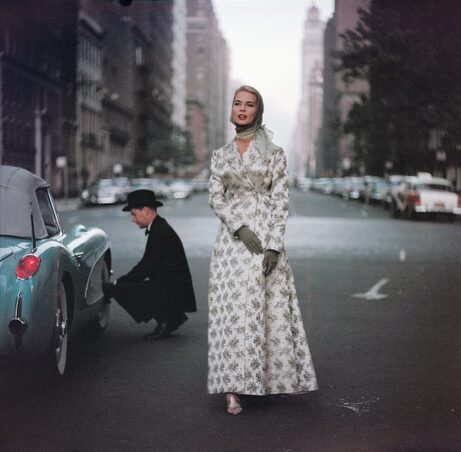

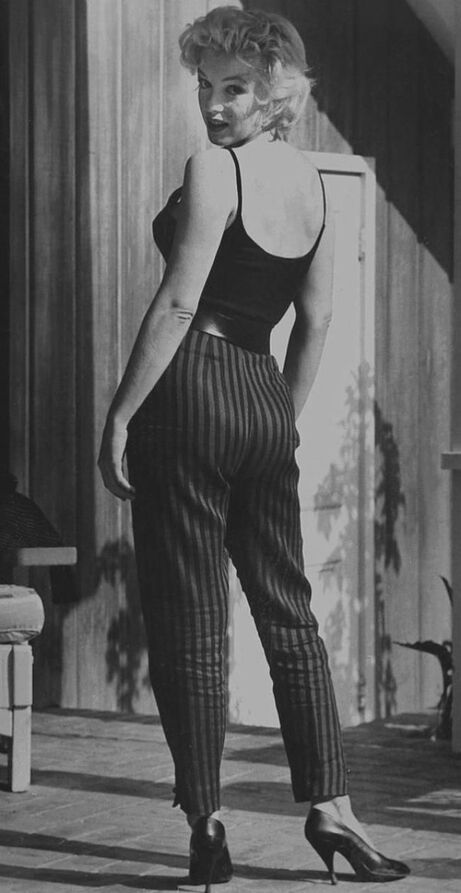

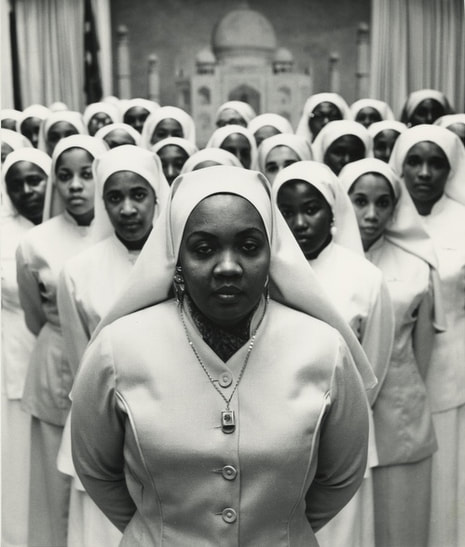

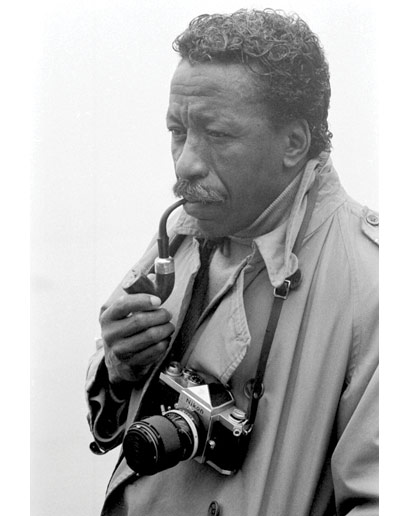

ProfileGordon Roger Alexander Buchanan Parks (November 30, 1912 – March 7, 2006) was an American photographer, musician, composer, writer, poet and film director, who became prominent in U.S. documentary photojournalism in the 1940s through 1970s and in glamour photography. Parks was the first African American to produce and direct major motion pictures, and best remembered for his iconic photos of poor Americans during the 1940s and for his photographic essays for Life magazine, and as the director of the 1971 film Shaft. BiographyParks was born in Fort Scott, Kansas on November 30, 1912, the youngest of fifteen children. His father was a farmer. His mother died when he was fourteen. He spent his last night at the family home sleeping beside his mother's coffin, seeking not only solace, but a way to face his own fear of death. At age 15, he started to work in brothels as a singer, piano player, and many other random jobs to survive. In 1929, he briefly worked in a gentlemen's club, where he was able to read many books from the club library. When the Wall Street Crash of 1929 brought an end to the club, he jumped on a train to Chicago, where he managed to land a job in a flophouse. A few years later, in 1933, he married his first wife Sally Alvis. At the age of 25, Parks was struck by photographs of migrant workers in a magazine. He bought his first camera, a Voigtländer Brillant, for $7.50 at a Seattle, Washington, pawnshop and taught himself how to take photos. The photography clerks who developed Parks's first roll of film applauded his work and prompted him to seek a fashion assignment at a women's clothing store in St. Paul, Minnesota, owned by Frank Murphy. Those photographs caught the eye of Marva Louis, wife of heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis. She encouraged Parks and his wife, Sally Alvis, to move to Chicago in 1940, where he began a portrait business and specialized in photographs of society women. Over the next few years, Parks moved from job to job, developing a freelance portrait and fashion photographer sideline. Following his resignation from the Office of War Information, Parks moved to Harlem and became a freelance fashion photographer for Vogue under the editorship of Alexander Liberman. Despite racist attitudes of the day, Vogue editor Liberman, hired him to shoot a collection of evening gowns. Parks photographed fashion for Vogue for the next few years and he developed the distinctive style of photographing his models in motion rather than in static poses. During this time, he published his first two books, Flash Photography (1947) and Camera Portraits: Techniques and Principles of Documentary Portraiture (1948). A 1948 photographic essay on a young Harlem gang leader won Parks a staff job as a photographer and writer with America's leading photo-magazine, Life. His involvement with Life would last until 1972. In 1961, Parks and his wife Sally Alcoa divorced. In 1962, he married Elizabeth Campbell, daughter of cartoonist E. Simms Campbell. During his years with Life, Parks wrote a few books on the subject of photography (particularly documentary photography), as well as several books of poetry, which he illustrated with his own photographs. He also wrote The Learning Tree (1963), a semi-autobiographical novel, followed by his first memoir A Choice of Weapons (1966) For over 20 years, Parks produced photographs on subjects including fashion, sports, Broadway, poverty, and racial segregation, as well as portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Muhammad Ali, and Barbra Streisand. He became "one of the most provocative and celebrated photojournalists in the United States.". And in 1960 he was named Photographer of the Year by the American Society of Magazine Photographers. In 1969 with his film adaptation of The Learning Tree for Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, Parks became Hollywood's first major black director. Parks wrote the screenplay himself and composed the musical score for the film, with assistance from his friend, the composer Henry Brant. Shaft, a 1971 detective film directed by Parks became a major hit. He then directed the 1972 sequel, Shaft's Big Score. In 1973, Parks and his second wife Elizabeth Campbell divorced, and he married Chinese-American Genevieve whom he met in 1962 when he began writing The Learning Tree, as his book editor. The couple divorced in 1979. For many years, Parks was romantically involved with Gloria Vanderbilt, the railroad heiress and designer. Their relationship evolved into a deep friendship that endured throughout his lifetime. 1990, Parks published his second volume memoir: Voices in the Mirror, and 15 years later, he wrote his third and last memoir A Hungry Heart in 2005. Gordon Parks died in March 7, 2006. Further interest

0 Comments

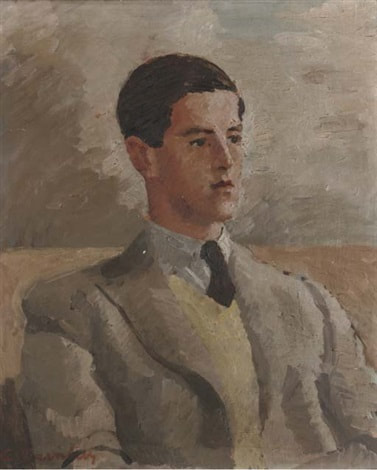

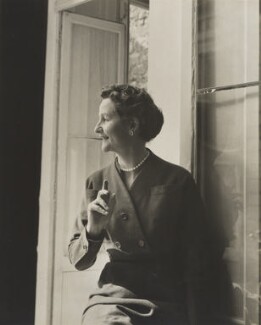

“Isn’t it awful to love clothes as much as I do, you know, I am not vain at all.¨ Profile of Nancy MitfordNancy Freeman-Mitford CBE (28 November 1904 – 30 June 1973), known as Nancy Mitford, was an English novelist, biographer and journalist. One of the Mitford sisters, she was regarded as one of the "Bright Young People" on the London social scene in the inter-war years. She wrote several novels about upper-class life in England and France and was considered a sharp and often provocative wit. She also established a reputation for herself as a writer of popular historical biographies. Mitford enjoyed a privileged childhood as the eldest daughter of the Hon. David Freeman-Mitford, later 2nd Baron Redesdale. Educated privately, she had no training as a writer before publishing her first novel in 1931. This early effort and the three that followed it created little stir; it was her two semi-autobiographical postwar novels, The Pursuit of Love (1945) and Love in a Cold Climate (1949), that established her reputation. Nancy Mitford married Peter Rodd in 1933 and they divorced in 1957 after a lengthy separation. During the Second World War she formed a liaison with a Free French officer, Gaston Palewski who became the love of her life, although he was never her formal lover. After the war Mitford settled in France and lived there until her death, maintaining social contact with her many English friends through letters and regular visits. During the 1950s Nancy Mitford was identified with the concept of "U" (upper) and "non-U" language, whereby social origins and standing were identified by words used in everyday speech. She had intended this as a joke, but many took it seriously, and Mitford was considered an authority on manners and breeding—possibly her most recognised legacy. Her later years were bitter-sweet, the success of her biographical studies of Madame de Pompadour, Voltaire and King Louis XIV contrasting with the ultimate failure of her relationship with Palewski. From the late 1960s her health deteriorated, and she endured several years of painful illness before her death in 1973. Biography of Nancy MitfordNancy Mitford's father, David Bertram Ogilvy Freeman-Mitford was a tea planter in Ceylon he who fought in the Boer War of 1899–1902 and was severely wounded, and her mother Sydney Bowles was the elder daughter of Thomas Gibson Bowles, a journalist, editor and magazine proprietor whose publications included Vanity Fair and The Lady. Nancy Mitford´s father worked as business manager of The Lady magazine, a post provided by her maternal grandfather, although he remained in this position for ten years, he had little interest in reading and knew nothing of business. Nancy Mitford´s parents married on 16 February 1904, and she was born on 28 November the same year, her day-to-day upbringing was delegated to her nanny and nursemaid, within the framework of her mother´s short-lived belief that children should never be corrected or be spoken to in anger. Before this experiment was discontinued, Nancy had become self-centred and uncontrollable. In summer of 1910 Nancy attended the nearby Francis Holland School and the few months she spent there represented almost the whole of her formal schooling; in the autumn the family moved to a larger house in Victoria Road, Kensington, after which Nancy was educated at home by successive governesses. Summers were spent at the family's cottage near High Wycombe, in Buckinghamshire, or with the children's Redesdale grandparents at Batsford Park. In 1921, after years of pleading for proper schooling, Nancy was allowed a year's boarding at Hatherop Castle, an informal private establishment for young ladies of good family. Here Nancy learned French and other subjects, played organised games and joined a Girl Guide troop. It was her first extended experience of life away from home, and she enjoyed it.The following year she was allowed to accompany four sisters on a cultural trip to Paris, Florence and Venice; her letters home are full of expressions of wonder at the sights and treasures: "I had no idea I was so fond of pictures ... if only I had a room of my own I would make it a regular picture gallery". Nancy's eighteenth birthday in November 1922 was the occasion for a grand "coming-out" ball, marking the beginning of her entry into Society. This was followed in June 1923 by her presentation at Court—a formal introduction to King George V at Buckingham Palace—after which she was officially "out" and could attend the balls and parties that constituted the London Season. She spent much of the next few years in a round of social events, making new friends and mixing with the "Bright Young People" of 1920s London. Nancy declared that "we hardly saw the light of day, except at dawn". In 1926 Asthall Manor was finally sold. While the new house at Swinbrook was made ready, the female members of the family were sent for three months to Paris, a period which began Nancy's "lifelong love affair" with France. Although she was now of age, her father maintained an aggressive hostility towards most of her male friends, these tended towards the frivolous, the aesthetic and the effeminate. Among them was Hamish St Clair Erskine, the second son of the 5th Earl of Rosslyn, an Oxford undergraduate four years Nancy's junior, who met her in 1928 and they became unofficially engaged, despite his homosexuality (of which Nancy may not have been aware). As a means of augmenting the meagre allowance provided by her father, Nancy Mitford began writing, encouraged by Evelyn Waugh, whom she met via her friend Evelyn Gardner. Her first efforts, anonymous contributions to gossip columns in society magazines, led to occasional signed articles, and in 1930 The Lady engaged her to write a regular column. That winter, she embarked on a full-length novel, Highland Fling, in which various characters—mostly identifiable among her friends, acquaintances and family—attend a Scottish house-party which develops chaotically. The book made little impact when it was published in March 1931, and she immediately began work on another, Christmas Pudding, Like the earlier novel, the plot centres on a clash between the "Bright Young People" and the older generation. Hamish Erskine is clearly identifiable in the character of "Bobby Bobbin" in the novel. Against a backdrop of negativity from family and friends the affair between Nancy Mitford and Hamish Erskine endured sporadically for several years until 1933 when Hamish Erskine ended it abruptly, annoucing to Nancy Mitford he was going to marry someone else. After their parting, Nancy wrote to him: "I thought in your soul you loved me & that in the end we should have children & look back on life together when we are old". Within a month of Erskine's departure, however, Nancy Mitford announced her engagement to Peter Rodd, the second son of Sir Rennell Rodd, a diplomat and politician who was ennobled that year as Baron Rennell. They were married on 4 December 1933, after which they settled into a cottage at Strand-on-the-Green on the western edges of London. Mitford's initial delight in the marriage was soon tempered by money worries, Rodd's fecklessness and her dislike of his family. By 1936 Mitford's marriage was largely a sham. Early in 1939 Rodd left for the South of France, to work with the relief organisations assisting the thousands of Spanish refugees who had fled from General Franco's armies in the final stages of the civil war. In 1932 Nancy Mitford's life was overshadowed by a family scandal involving her younger sister Diana Mitford, who had married Bryan Guinness in 1928 bur deserted her husband and their two children to become the mistress of Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists, himself married with three children. Nancy was the only one who offered her sister support, regularly visiting her and keeping her up to date with family news and social gossip. In September 1942 Nancy Mitford met Gaston Palewski, a French colonel attached to General Charles de Gaulle's London staff. She found him fascinating, and he became the love of her life—though her feelings were never fully reciprocated—and an inspiration for much of her future writing. In 1944, with Evelyn Waugh's encouragement, Nancy Mitford began planning a new novel. In March 1945 she was given three months' leave from the shop to write it. The Pursuit of Love is a heavily autobiographical romantic comedy in which many of her family and acquaintances appear in thin disguises. The book sold 200,000 copies within a year of publication, and firmly established Mitford as a best-selling author.  Mitford’s most enduringly popular novel, The Pursuit of Love is a classic comedy about growing up and falling in love among the privileged and eccentric. Mitford modeled her characters on her own famously unconventional family. We are introduced to the Radletts through the eyes of their cousin Fanny, who stays with them at Alconleigh, their Gloucestershire estate. Uncle Matthew is the blustering patriarch, known to hunt his children when foxes are scarce; Aunt Sadie is the vague but doting mother; and the seven Radlett children, despite the delights of their unusual childhood, are recklessly eager to grow up. The first of three novels featuring these characters, The Pursuit of Love follows the travails of Linda, the most beautiful and wayward Radlett daughter, who falls first for a stuffy Tory politician, then an ardent Communist, and finally a French duke named Fabrice. At the end of the war Peter Rodd returned to Nancy from the war, but their marriage was essentially over; although remaining on friendly terms, the couple led separate lives, and in April 1946, Nancy left London to make her permanent home in Paris and never lived in England again. During her first 18 months in Paris Mitford lived in several short-term lodgings while enjoying a hectic social life, the hub of which was the British Embassy under the regime of the ambassador, Duff Cooper, and his socialite wife Lady Diana Cooper. Eventually Mitford found a comfortable apartment, with a maid, at No. 7 rue Monsieur on the Left Bank, close to Palewski's residence. Settled there in comfort, she established a pattern to her life that she mostly followed for the next 20 years, her precise timetable determined by Palewski's varying availability. Her socialising, entertaining and working were interspersed with regular short visits to family and friends in England and summers generally spent in Venice. In 1948 Nancy Mitford completed a new novel, a sequel to The Pursuit of Love she called Love in a Cold Climate, with the same country house ambience as the earlier book and many of the same characters. The novel's reception was even warmer than that of its predecessor; In 1950 she translated and adapted André Roussin's play La petite hutte ("The Little Hut"), in preparation for its successful West End début in August, and the play ran for 1,261 performances, and provided Mitford with a steady £300 per month in royalties. The same year The Sunday Times asked her to contribute a regular column, which she did for four years. This busy period in her writing life continued in 1951 with her third postwar novel, The Blessing, another semi-autobiographical romance this time set in Paris, in which an aristocratic young Englishwoman is married to a libidinous French marquis. Evelyn Waugh (to whom the book was dedicated) found the book "admirable, deliciously funny, consistent and complete, by far the best of your writings". Mitford then began her first serious non-fiction work, a biography of Madame de Pompadour, and in 1957, she published Voltaire in Love, an account of the love affair between Voltaire and the Marquise du Châtelet, which she considered it her first truly grown-up work, and her best. In October 1960 Nancy Mitford published Don't Tell Alfred, in which she revived Fanny Wincham, the narrator of The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate, and placed her in a Paris setting as wife of the British ambassador. The book was popular with the public, but received indifferent reviews, and she decided she would write no more fiction  In this delightful comedy, Fanny—the quietly observant narrator of Nancy Mitford’s two most famous novels—finally takes center stage. Fanny Wincham—last seen as a young woman in The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate—has lived contentedly for years as housewife to an absent-minded Oxford don, Alfred. But her life changes overnight when her beloved Alfred is appointed English Ambassador to Paris. Soon she finds herself mixing with royalty and Rothschilds while battling her hysterical predecessor, Lady Leone, who refuses to leave the premises. When Fanny’s tender-hearted secretary begins filling the embassy with rescued animals and her teenage sons run away from Eton and show up with a rock star in tow, things get entirely out of hand. Gleefully sending up the antics of mid-century high society, Don’t Tell Alfred is classic Mitford. In 1964 Nancy began work on The Sun King, a biography of King Louis XIV and it was published in August 1966, among the many tributes to the book was that of President de Gaulle, who recommended it to every member of his cabinet. As her landlord on 7 rue Monsieur increased her rent, Nancy decided to leave Paris and buy herself a house in Versailles and moved to No. 4 rue d'Artois, Versailles, in January 1967. The modest house had a half-acre (0.2 hectare) garden, which soon became one of her chief delights. In 1968 she began work on her final book, a biography of Frederick the Great. After a series of illnesses she learned from a newspaper announcement that Palewski had married the Duchesse de Sagan, a rich divorcée. Shortly after, she entered hospital for the removal of a tumour. After the operation she continued to suffer pain, although she was able to continue working on her book Frederick the Great which was published later in 1970 to a muted reception. Mitford's remaining years were dominated by her illness, although for a time she enjoyed visits from her sisters and friends, and working in her garden. In April 1972 the French government made her a Chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur, and later that year the British government appointed her a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). She was delighted by the former honour, and amused by the latter

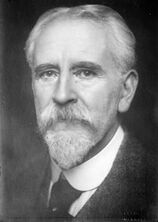

At the end of 1972 she entered the Nuffield Clinic in London, where she was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma, a cancer of the blood. She lived for another six months, unable to look after herself and in almost constant pain, struggling to keep her spirits up. She wrote to her friend James Lees-Milne: "It's very curious, dying, and would have many a drôle amusing & charming side were it not for the pain". She died on 30 June 1973 at her home in the rue d'Artois and was cremated in Versailles. birth place: London England birth date: 27 November 1853 zodiac sign: Sagittarius death place: London England death date: 17 October 1928 Sir Francis Bernard Dicksee (or Frank Bernard Dicksee) was an English Victorian painter and illustrator, best known for his pictures of dramatic literary, historical, and legendary scenes. He also was a noted painter of portraits of fashionable women, which helped to bring him success in his own time. Francis Bernard Dicksee was born at a time when the first wave of Pre-Raphaelitism was beginning to make its presence felt in Britain and he inherited the romantic spirit of the movement that had been founded only a stone's throw from his childhood home in the Bloomsbury area of London.. After early success with his painting of unrequited love, Harmony, he rose to be one of the most popular artists of the late 19th-century, painting in a sumptuous and dramatic style. Dicksee's family was a veritable dynasty of artists, his father, brother, and sister Margaret were all well-known painters, but it is Francis who is best known and loved today for his Pre-Raphaelite inspired subjects. Dicksee's father, Thomas Dicksee, was a painter who taught Frank as well as his sister Margaret from a young age. Dicksee enrolled in the Royal Academy in 1870. Amongst the visiting lecturers who trained him, were the famous senior academicians Leighton [1830-1896] and Millais [1829-1896]. Dicksee was a star student, earning many distinctions and medals. Like many other artists of the day his early career was largely spent in book illustration, as well as some stained glass window design. He started exhibiting at the RA in the mid 1870s, and also exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery, though his real base was always the Academy. Dicksee made his reputation with Harmony, exhibited at the Academy in 1877, and bought by the Chantry Bequest. Many of his pictures were of dramatic historical and legendary scenes. He also was a noted painter of elegant, highly-finished portraits of fashionable women, which of course helped to bring him material success. He also painted landscapes. Dicksee lived in St John's Wood, and remained a bachelor. He was, of course, one of the nineteenth century artists who outlived his time, and was, to his credit, very unhappy with developments in the early twentieth century. Rather surprisingly, Dicksee was elected President of the Royal Academy in 1924, fulfilling the role with panache and tact. Physically he was a tall, good-looking, patrician figure, with a charming easy-going manner. Like his predecessor but one Edward Poynter [1836-1919], the traditional orientation of his art gradually isolated him from the artistic mainstream of the day. He was knighted in 1925, and named to the Royal Victorian Order by King George V in 1927. In 1921 Dicksee exhibited at the first exhibition of the Society of Graphic Art in London. Dicksee painted The Funeral of a Viking (1893; Manchester Art Gallery), which was donated in 1928 by Arthur Burton in memory of his mother to the Corporation of Manchester. Victorian critics gave it both positive and negative reviews, for its perfection as a showpiece and for its dramatic and somewhat staged setting, respectively. The painting was used by Swedish Viking/Black metal band Bathory for the cover of their 1990 album, Hammerheart. A book on Frank Dicksee's life and work with a full catalogue of his known paintings and drawings by Simon Toll was published by Antique Collector's Club in 2016. Further reading Articles and Websites Books  Title: Frank Dicksee:1853-1928: His art and life Author: Simon Toll |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|