|

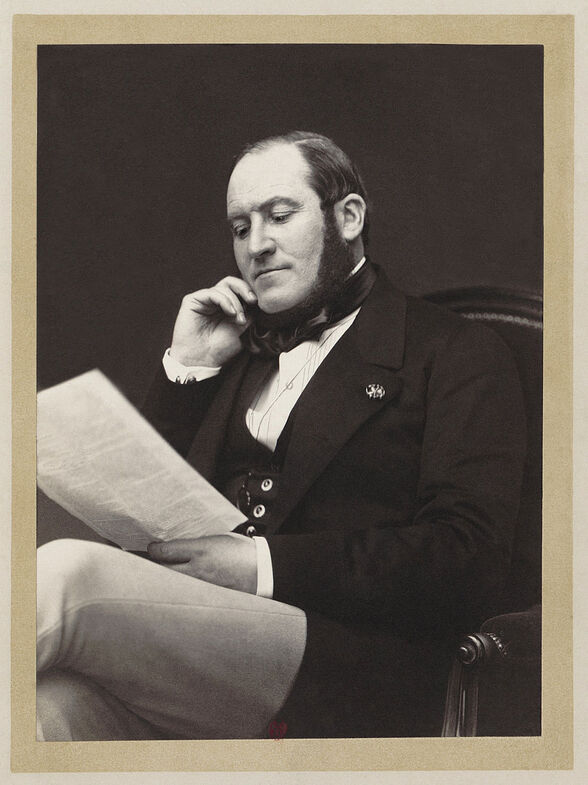

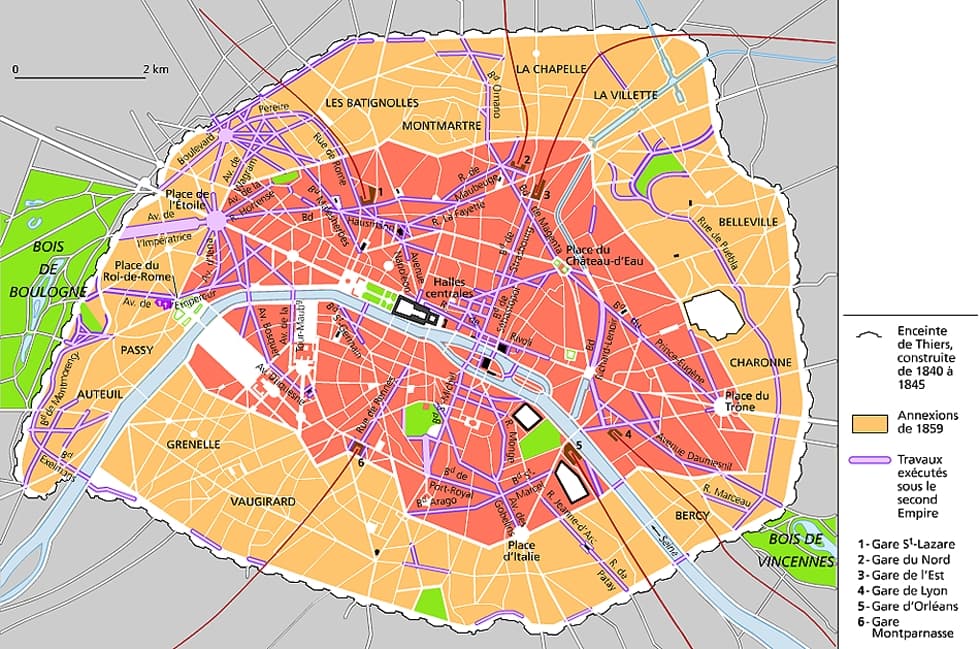

Georges-Eugène Haussmann, commonly known as Baron Haussmann (27 March 1809 – 11 January 1891), was a French official who served as prefect of Seine (1853–1870), chosen by Emperor Napoleon III to carry out a massive urban renewal programme of new boulevards, parks and public works in Paris commonly referred to as Haussmann's renovation of Paris. Critics forced his resignation for extravagance, but his vision of the city still dominates central Paris. Georges Eugène Haussmann, communément appelé le baron Haussmann, né le 27 mars 1809 à Paris et mort le 11 janvier 1891 dans la même ville, est un haut fonctionnaire et homme politique français. Préfet de la Seine de 1853 à 1870, il a dirigé les transformations de Paris sous le Second Empire en approfondissant le vaste plan de rénovation établi par la commission Siméon, qui vise à poursuivre les travaux engagés par ses prédécesseurs à la préfecture de la Seine, Rambuteau et Berger. Les transformations sont telles que l'on parle de bâtiments « haussmanniens » pour les nombreux édifices construits le long des larges avenues percées dans Paris sous sa houlette, les travaux réalisés ayant donné à l'ancien Paris médiéval le visage qu'on lui connait aujourd'hui. BiographyGeorges-Eugène Haussmann was born on 27 March 1809, at 53 Rue du Faubourg-du-Roule, in the Beaujon neighbourhood of Paris, the son of Nicolas-Valentin Haussmann and of Ève-Marie-Henriette-Caroline Dentzel, both of German families. His paternal grandfather Nicolas was a deputy of the Legislative Assembly and National Convention, an administrator of the department of Seine-et-Oise and a commissioner to the army. His maternal grandfather was a general and a deputy of the National Convention: Georges Frédéric Dentzel, a baron of Napoleon's First Empire. He began his schooling at the Collège Henri-IV and at the Lycée Condorcet in Paris, and then began to study law. At the same time, he studied music as a student at the Paris Conservatory, as he was a talented musician. Haussmann joined his father as an insurgent in the July Revolution of 1830, which deposed the Bourbon king Charles X in favor of his cousin, Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans. He was married on 17 October 1838 in Bordeaux to Octavie de Laharpe. They had two daughters: Henriette, who married the banker Camille Dollfus in 1860, and Valentine, who married Vicomte Maurice Pernéty, the chief of staff of his department, in 1865. Valentine divorced Pernéty in 1891. She then married Georges Renouard (1843–1897). On 21 May 1831, Haussmann began his career in public administration. Despite proving himself as a hard worker and able representative of the government, his arrogance, dictatorial manner, and habit of impeding his superiors led to his being continually passed over for promotion. Only after the 1848 Revolution swept away the July Monarchy, establishing the Second Republic in its place, did Haussmann's fortunes change. Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, became the first elected president of France in 1848. Haussmann travelled to Paris in January 1849 to meet the Minister of the Interior and the new president. He was deemed to be a loyal holdover from the civil service of the July Monarchy, and shortly after their meeting Louis Napoléon granted Haussmann a promotion to prefect of the Var Department at Draguignan. In 1850, Louis Napoléon started an ambitious project to connect the Louvre to the Hôtel de Ville in Paris by extending the Rue de Rivoli and create a new park, the Bois de Boulogne, on the outskirts of the city, but he was exasperated by the slow progress made by the incumbent prefect of the Seine, Jean-Jacques Berger. Louis-Napoleon was highly popular, but he was blocked from running for re-election by the constitution of the Second French Republic. At the end of December 1851, he staged a coup d'état, and in 1852 declared himself Emperor of the French under the title Napoleon III, and he soon began searching for a new prefect of the Seine to carry out his Paris reconstruction program. The emperor's minister of the interior, Victor de Persigny, interviewed the prefects of Rouen, Lille, Lyon, Marseille and Bordeaux for the Paris post. In his memoirs, he described his interview with Haussmann, then prefect of the Gironde out of Bordeaux: "It was Monsieur Haussmann who impressed me the most. It was a strange thing, but it was less his talents and his remarkable intelligence that appealed to me, but the defects in his character. I had in front of me one of the most extraordinary men of our time; big, strong, vigorous, energetic, and at the same time clever and devious, with a spirit full of resources. This audacious man wasn't afraid to show who he was. ... He told me all of his accomplishments during his administrative career, leaving out nothing; he could have talked for six hours without a break, since it was his favourite subject, himself. I wasn't at all displeased. ... It seemed to me that he was exactly the man I needed to fight against the ideas and prejudices of a whole school of economics, against devious people and skeptics coming from the Stock Market, against those who were not very scrupulous about their methods; he was just the man. Whereas a gentleman of the most elevated spirit, cleverness, with the most straight and noble character, would inevitably fail, this vigorous athlete ... full of audacity and skill, capable of opposing expedients with better expedients, traps with more clever traps, would certainly succeed. I told him about the Paris works and offered to put him in charge." Persigny sent Haussmann to Napoleon III who made him prefect of the Seine on 22 June 1853, which post Haussmann held until 1870. On 29 June, the emperor gave him the mission of making the city healthier, less congested and grander. Napoleon III and Haussmann launched a series of enormous public works projects in Paris, hiring tens of thousands of workers to improve the sanitation, water supply and traffic circulation of the city. Napoleon III installed a huge map of Paris in his office, marked with coloured lines where he wanted new boulevards to be. For the nearly two decades of Napoleon III's reign, and for a decade afterwards, most of Paris was an enormous construction site. Beginning in 1854, in the centre of the city, Haussmann's workers tore down hundreds of old buildings and cut eighty kilometres of new avenues, connecting the central points of the city. Buildings along these avenues were required to be the same height and in a similar style, and to be faced with cream-coloured stone, creating the uniform look of Paris boulevards. Victor Hugo mentioned that it was hardly possible to distinguish what the house in front of you was for: theatre, shop or library. Haussmann managed to rebuild the city in 17 years. The reconstruction of the centre of Paris was the largest such public works project ever undertaken in Europe, for which Haussmann spent 2.5 billion francs. never before had a major city been completely rebuilt when it was still intact; London, Rome, Copenhagen and Lisbon had been rebuilt after major fires or earthquakes. To thank Haussmann for his work, Napoleon III proposed in 1857 to make Haussmann a member of the French Senate and to give him an honorary title, as he had done for some of his generals. Haussmann asked for the title of baron, which, as he said in his memoirs, had been the title of his maternal grandfather, Georges Frédéric, Baron Dentzel, a general under the first Napoleon, of whom Haussmann was the only living male descendant. According to his memoirs, he joked that he might consider the title aqueduc (a pun on the French words for 'duke' and 'aqueduct') but that no such title existed. This use of baron, however, was not officially sanctioned, and he remained, legally, Monsieur Haussmann. During the first half of the reign of Napoleon III, the French legislature had very little real power; all decisions were made by the Emperor. Beginning in 1860, however, Napoleon decided to liberalise the Empire and give the legislators real power. The members of the opposition in the parliament increasingly aimed their criticism of Napoleon III at Haussmann, criticising his spending and his high-handed attitude toward the parliament. The republican opposition to Napoleon III won many parliamentary seats in the 1869 elections, and increased its criticism of Haussmann. Napoleon III gave in to the criticism and named an opposition leader and fierce critic of Haussmann, Emile Ollivier, as his new prime minister. Haussmann was invited to resign. Haussmann refused to resign, and was relieved of his duties by the Emperor on 5 January 1870 in order to improve Napoleon III's own flagging popularity. Six months later, during the Franco-German War, Napoleon III was captured by the Germans, and the Empire was overthrown. In his memoires, Haussmann had this comment on his dismissal: "In the eyes of the Parisians, who like routine in things but are changeable when it comes to people, I committed two great wrongs; over the course of seventeen years I disturbed their daily habits by turning Paris upside down, and they had to look at the same face of the Prefect in the Hotel de Ville. These were two unforgivable complaints." After the fall of Napoleon III, Haussmann spent about a year abroad, but he re-entered public life in 1877, when he became Bonapartist deputy for Ajaccio. His later years were occupied with the preparation of his Mémoires (three volumes, 1890–1893). Some of the contemporary critics of Haussmann softened their views over time. Jules Simon, an ardent republican, and a fierce critic of Haussmann in the parliament, wrote of Haussmann in the Gaulois in 1882: "He tried to make Paris a magnificent city, and he succeeded completely. When he took Paris in hand and managed our affairs, rue Saint-Honore and rue Saint-Antoine were still the largest streets in the city. We had no other promenades than the Grands Boulevards and the Tuileries; the Champs-Élysées was most of the time a sewer; the Bois-de-Boulogne was at the end of the world. We were lacking water, markets, light, in those far-off times, which are only thirty years past. He demolished neighbourhoods- one could say, entire cities. They cried that he would create a plague; he let us cry and, on the contrary, through his intelligent piercing of streets, he gave us air, health and life. Here he created a street; there he created an avenue or a boulevard; here a Place, a Square; a Promenade. Out of emptiness he made the Champs-Élysées, the Bois de Boulogne, de the Bois de Vincennes. He introduced, into his beautiful capital, trees and flowers, and populated it with statues." Haussmann died in Paris on 11 January 1891 at age 82 and was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery. His wife, Louise-Octavie de la Harpe, had died just eighteen days earlier. At the time of their deaths, they had resided in an apartment at 12 rue Boissy d'Anglas, near the Place de la Concorde. The will transferred their estate to the family of their only surviving daughter, Valentine Haussmann. Haussmann's plan for Paris inspired the urban planning and creation of similar boulevards, squares and parks in Cairo, Buenos Aires, Brussels, Rome, Vienna, Stockholm, Madrid, and Barcelona. After the Paris International Exposition of 1867, William I, the King of Prussia, carried back to Berlin a large map showing Haussmann's projects, which influenced the future planning of that city. His work also inspired the City Beautiful Movement in the United States. Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of Central Park in New York, visited the Bois de Boulogne eight times during his 1859 study trip to Europe. The American architect Daniel Burnham borrowed liberally from Haussmann's plan and incorporated the diagonal street designs in his 1909 Plan of Chicago. BiographieGeorges Eugène Haussmann naît à Paris le 27 mars 1809 au 53, rue du Faubourg-du-Roule, dans le quartier Beaujon. Il est le fils de Nicolas-Valentin Haussmann (1787-1876), protestant, commissaire des guerres et intendant militaire de Napoléon Ier, et d'Ève-Marie-Henriette-Caroline Dentzel. Par sa mère, il est le petit-fils du général et député de la Convention Georges Frédéric Dentzel, baron d'Empire, et, par son père, le petit-fils de Nicolas Haussmann (1760-1846), député de l'Assemblée législative et de la Convention, administrateur du département de Seine-et-Oise, commissaire aux armées. Il fait ses études au lycée Condorcet à Paris puis entame un cursus de droit tout en étant élève au conservatoire de musique de Paris. Il est sous-préfet de Nérac en Lot-et-Garonne le 9 octobre 1832). En poste à Nérac, il fréquente la bourgeoisie bordelaise, au sein de laquelle il rencontre Louise Octavie de Laharpe, avec laquelle il se marie le 17 octobre 1838 à Bordeaux. Ils ont deux filles : Henriette, qui épouse en 1860 Camille Dollfus, homme politique, et Valentine, qui épouse en 1865 le vicomte Maurice Pernety, chef de cabinet du préfet de la Seine, puis, après son divorce (1891), Georges Renouard (1843-1897), fils de Jules Renouard. Il a une autre fille, Eugénie (née en 1859), de sa relation avec l'actrice Francine Cellier (1839-1891), et descendance. Sous l'administration d'Haussmann, les travaux et projets girondins ont été importants. Présenté à Napoléon III par Victor de Persigny, ministre de l'Intérieur, il devient préfet de la Seine le 22 juin 1853, jusqu'en janvier 1870. Le 29 juin 1853, l'empereur lui confie la mission d'assainir et embellir Paris. En 1857, il devient sénateur. Son titre de baron a été contesté. Comme il l'explique dans ses Mémoires, il a utilisé ce titre après son élévation au Sénat en 1857, en vertu d'un décret de Napoléon Ier qui accordait ce titre à tous les sénateurs, mais ce décret était tombé en désuétude depuis la Restauration. Son œuvre n'en reste pas moins contestée à cause des sacrifices qu'elle a entraînés ; en outre, les méthodes employées ne s'encombrent pas de principes démocratiques. Les manœuvres financières sont bien souvent spéculatives et douteuses, ce qui nourrit le récit d'Émile Zola dans son roman La Curée. Haussmann est destitué par le cabinet d'Émile Ollivier le 5 janvier 1870, quelques mois avant la chute de Napoléon III. Après s'être retiré pendant quelques années à Cestas près de Bordeaux, Haussmann revient à la vie publique en étant élu député en Corse en 1877, face au député sortant, Napoléon-Jérôme Bonaparte, avec le soutien du nonce apostolique et du cardinal Guibert, archevêque de Paris. Il conserve ce mandat jusqu'en 1881 : il siège dans le groupe bonapartiste de l’Appel au peuple. Il est écarté de la vie publique en 1885 et en 1890, il perd successivement sa fille aînée et sa femme. Il consacre la fin de sa vie à la rédaction de ses Mémoires (1890-1891), un document important pour l'histoire de l'urbanisme de Paris. Haussmann, mort le 11 janvier 1891, est enterré au cimetière du Père-Lachaise à Paris. L'action d'Haussmann a influencé l'aménagement urbain de plusieurs villes françaises sous le Second Empire et le début de la Troisième République.

Hors de France, plusieurs capitales — Bruxelles, Rome, Barcelone, Madrid, Buenos Aires et Stockholm — s'inspirent de ses idées, avec l'ambition de devenir un nouveau Paris. Les principes haussmanniens influencent aussi Istanbul et Le Caire. Bucarest dispose d'un quartier en rupture avec la vieille ville appelé « le petit Paris ».

1 Comment

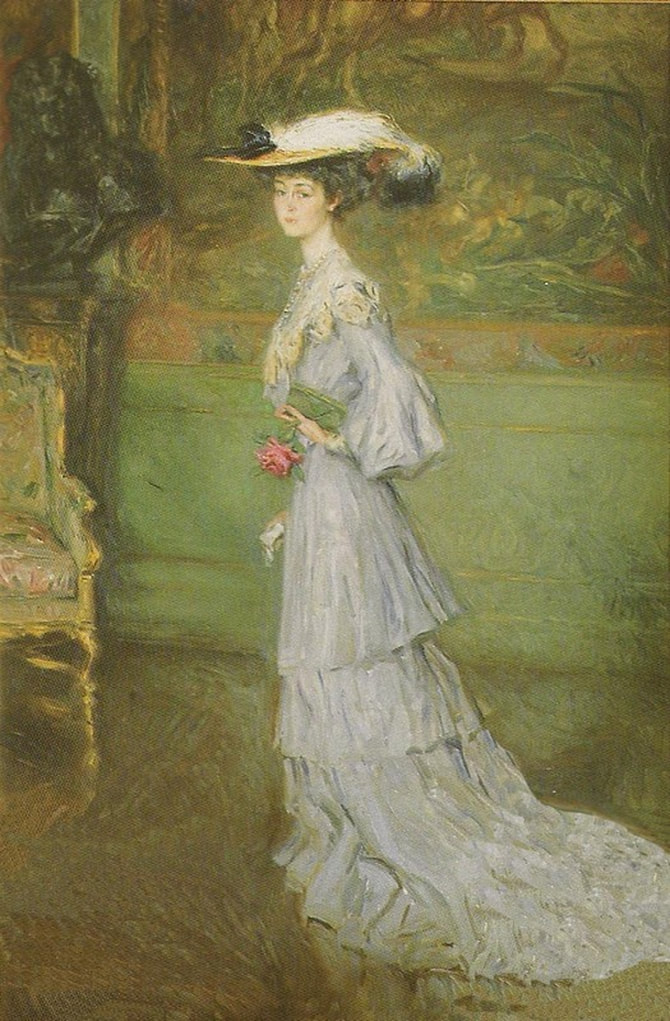

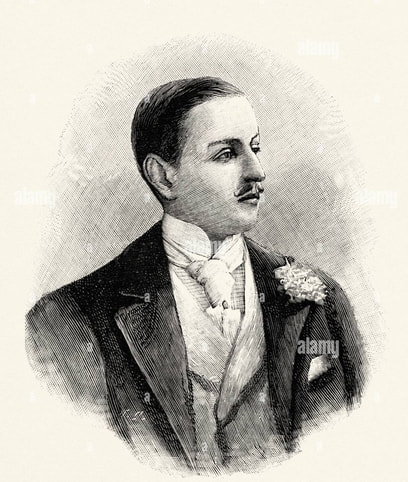

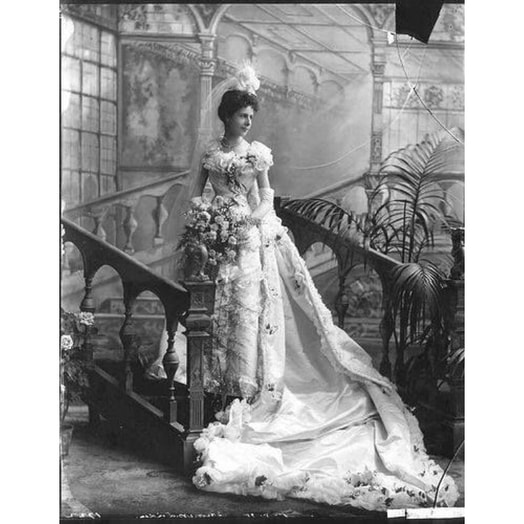

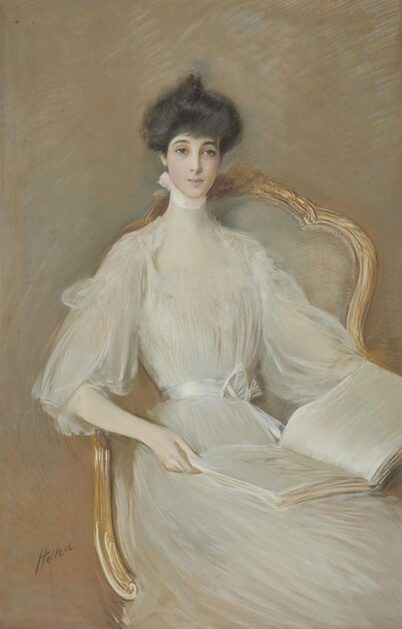

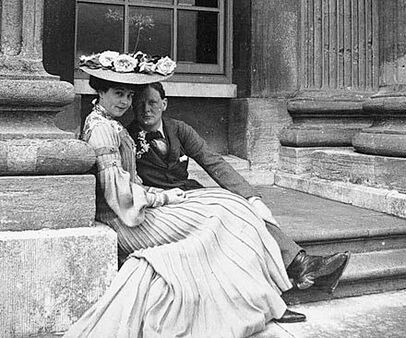

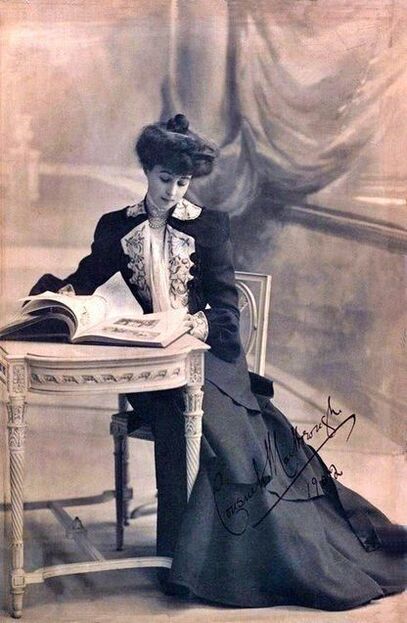

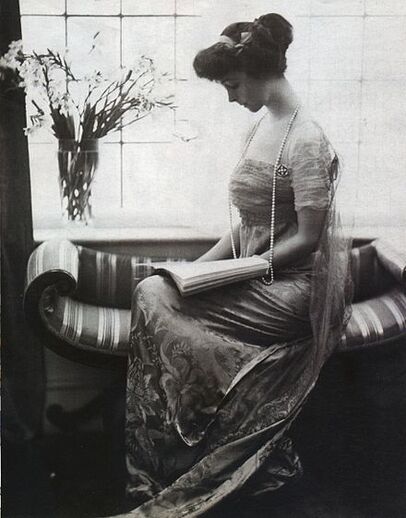

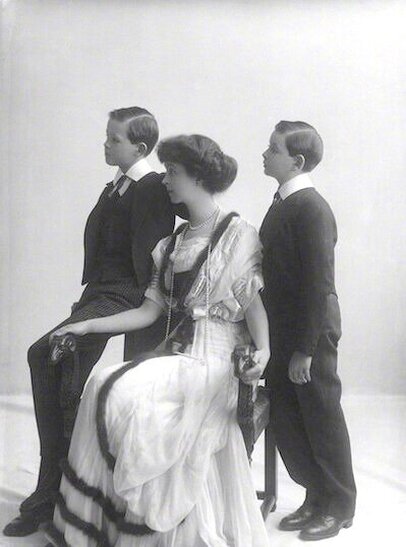

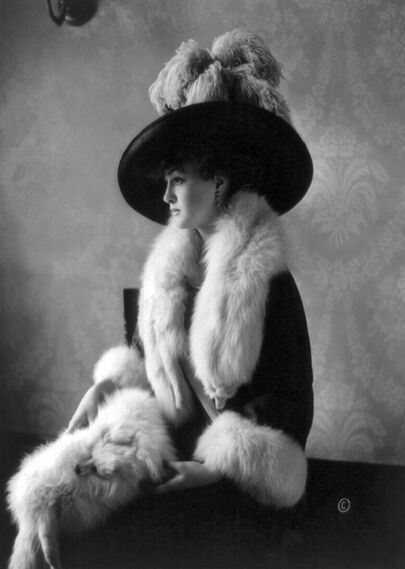

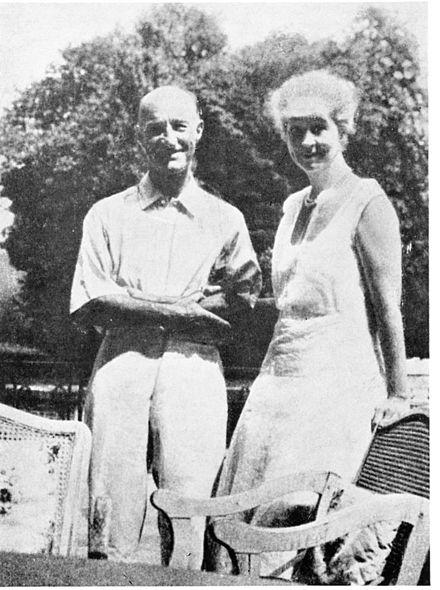

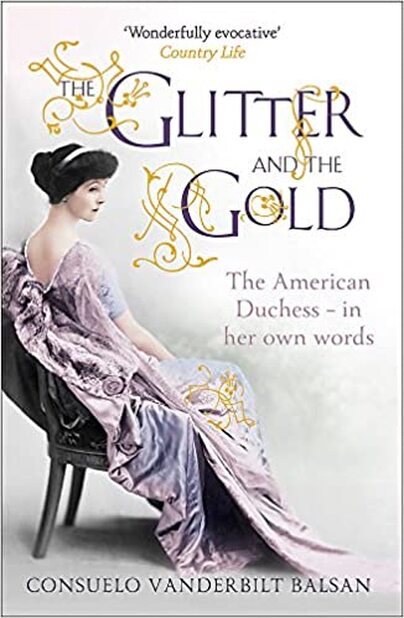

Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan (formerly Consuelo Spencer-Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough; born Consuelo Vanderbilt; 2 March 1877 – 6 December 1964) was a member of the prominent American Vanderbilt family. Her first marriage to the ninth Duke of Marlborough has become a well-known example of one of the advantageous, but loveless, marriages common during the Gilded Age. The Duke obtained a large dowry by the marriage, and reportedly told her just after the marriage that he married her in order to "save Blenheim" Palace, his ancestral home. Consuelo Vanderbilt and her friends were the inspiration for Edith Wharton's unfinished novel The Buccaneers. Although the teenage Consuelo was opposed to the marriage arranged by her mother, she became a popular and influential Duchess. For much of the marriage, the Marlboroughs lived separately and the marriage was finally annulled. She went on to marry a wealthy French aviator and continued her charitable endeavours. BiographyBorn in New York City, Consuelo Vanderbilt was the only daughter and eldest child of William Kissam Vanderbilt, a New York railroad millionaire, and his first wife, a Southern belle Alva Erskine Smith (1853–1933, who later married Oliver Belmont) from Mobile, Alabama, the daughter of a cotton broker. Her Spanish name was in honor of her godmother, Consuelo Yznaga (1853–1909), a half-Cuban, half-American socialite who created a social stir a year earlier when she married the fortune-hunting George, Viscount Mandeville, a union of Old World aristocracy and New World money that caused the groom's father, the 7th Duke of Manchester, to openly wonder if his son and heir had married a "Red Indian". Consuelo Vanderbilt was largely dominated by her mother, who was determined that her daughter would make a great marriage like that of her famous namesake. In her autobiography, Consuelo Vanderbilt described how she was required to wear a steel rod, which ran down her spine and fastened around her waist and over her shoulders, to improve her posture. She was educated entirely at home by governesses and tutors, and learned foreign languages at an early age. Her mother was abusive and whipped her with a riding crop for minor infractions. When, as a teenager, Consuelo objected to the clothing her mother had selected for her, Alva told her that "I do the thinking, you do as you are told." Consuelo Vanderbilt was considered a great beauty, with a face compelling enough to cause the playwright Sir James Barrie, author of Peter Pan, to write, "I would stand all day in the street to see Consuelo Marlborough get into her carriage." And she attracted numerous title-bearing suitors anxious to trade social position for cash. Her mother reportedly received at least five proposals for her hand. Consuelo was allowed to consider the proposal of just one of the men, Prince Francis Joseph of Battenberg, but she developed an instant aversion to him. None of the others, however, was good enough for Alva Vanderbilt, who wasdetermined to secure the highest-ranking mate possible for her only daughter, a union that would emphasize the preeminence of the Vanderbilt family in New York society. With the help of Lady Paget, the wife of Sir Arthur Paget, and daughter of an socially ambitious widow of an American hotel entrepreneur, Alva Vanderbilt engineered a meeting between Consuelo and the indebted, titled Charles Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough, chatelain of Blenheim Palace. Lady Paget, always short of money, soon became a sort of international marital agent, introducing eligible American heiresses to British noblemen. Consuelo Vanderbilt had no interest in the duke, being secretly engaged to an American, Winthrop Rutherfurd. Her mother cajoled, wheedled, begged, and then, ultimately, ordered her daughter to marry Marlborough. When Consuelo – a docile teenager whose only notable characteristic at the time was abject obedience to her fearsome mother – made plans to elope, she was locked in her room as Alva threatened to murder Rutherfurd. Still she refused. It was only when Alva Vanderbilt claimed that her health was being seriously and irretrievably undermined by Consuelo's stubbornness and appeared to be at death's door that the malleable girl acquiesced. Alva made an astonishing recovery from her entirely phantom illness, and when the wedding took place, Consuelo stood at the altar reportedly weeping behind her veil. The duke, for his part, gave up the woman he reportedly loved back in England and collected US$2.5 million (approximately US$75.2 million in 2019 dollars) in railroad stock as a marriage settlement. His purpose of marrying her was to restore his beloved Bleinheim Palace in Oxfordshire. Consuelo Vanderbilt married Charles Spencer-Churchill, The 9th Duke of Marlborough at St. Thomas Episcopal Church, New York City, on 6 November 1895. After her marriage, Consuelo Vanderbilt's father built a mansion for her in London, Sunderland House in Curzon Street. The new Duchess of Marlborough was adored by the poor and less fortunate tenants on her husband's estate, whom she visited and to whom she provided assistance. She later became involved with other philanthropic projects and was particularly interested in those that affected mothers and children. She was also a social success with royalty and the aristocracy of Britain. Consuelo Vanderbilt gave birth to two sons, John Albert William Spencer-Churchill, Marquess of Blandford (who became 10th Duke of Marlborough) and Lord Ivor Spencer-Churchill. However, given the ill-fitting match between the duke and his wife, it was only a matter of time before their marriage was in name only. The duchess eventually was smitten with her husband's cousin, the Hon. Reginald Fellowes, while the duke fell under the spell of Gladys Marie Deacon, an eccentric American of little money but, like Consuelo, dazzling to look at and of considerable intellect. The Marlboroughs separated in 1906. Consuelo Vanderbilt and Charles Spencer-Churchill, The Duke of Marlborough divorced in 1921. Shortly afterwards, on 25 June 1921 The Duke of Marlborough married Gladys Deacon. A few days later, on 4 July 1921, Consuelo Vanderbilt married Colonel Jacques Balsan, a textile manufacturing heir and a record-breaking pioneer French balloon, aircraft, and hydroplane pilot who once worked with the Wright Brothers. Jacques Balsan was a younger brother of Etienne Balsan, who was an early lover of Coco Chanel. On 19 August 1926, the marriage of Consuelo Vanderbilt and The Duke of Marlborough was annulled, at the duke's request and with Consuelo's assent, Though largely embarked upon as a way to facilitate the Anglican duke's desire to convert to Roman Catholicism, the annulment, to the surprise of many, also was fully supported by the former duchess's mother, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, who testified that the Vanderbilt–Marlborough marriage had been an act of unmistakable coercion. In later years, Consuelo and her mother enjoyed a closer, easier relationship. After the annulment of her marriage to the Duke of Marlborough, Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan still maintained ties with favorite Churchill relatives, particularly Winston Churchill, cousin of The 9th Duke of Marlborough. He was a frequent visitor to her château, in Saint-Georges-Motel, a small commune near Dreux about 50 miles from Paris, in the 1920s and 1930s, where he completed his last painting before the war. Records in Florida show that in 1932 Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan built a home in Manalapan, Florida, just south of Palm Beach. It was designed as a love nest by Maurice Fatio. The dream home of 26,000 square feet is called Casa Alva, in honor of her mother. Although Consuelo sold her home in 1957, it still exists. The Duke of Marlborough and his new wife Gladys Deacon's marriage did not turn out to be a happy one. Gladys Deacon, famed for her Greek beauty became increasingly eccentric and evicted from Blenheim Palace. On 30 June 1934, The Duke of Marlborough died of heart attack, at age 88. Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan published her insightful but not entirely candid autobiography, The Glitter and the Gold, in 1953. It was ghostwritten by Stuart Preston, an American writer who was an art critic for The New York Times. A reviewer in the same paper called it "an ideal epitaph of the age of elegance." Jacques Balsan died in New York on 4 November 1956 at the age of 88. Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan died at Southampton, Long Island, New York, on 6 December 1964. She was buried alongside her younger son, Lord Ivor Spencer-Churchill, in the churchyard at St Martin's Church, Bladon, Oxfordshire, England, near her former home, Blenheim Palace. During World War I, Consuelo Vanderbilt worked as the chair of the Economic Relief Committee for the American Women's War Relief Fund.

During the inter-war period, she and Winaretta Singer-Polignac (the Princess de Polignac and Singer Sewing Machine heiress) worked together in the construction of a 360-bed hospital destined to provide medical care to middle class workers. The result of this effort is the Foch Hospital, located in Suresnes, a suburb of Paris, France. The hospital also includes a school of nursing and is one of the top ranked hospitals in France, especially for renal transplants. It has remained true to its origins and stayed a private not-for-profit institution that still serves the Paris community. It is managed by the Fondation médicale Franco-américaine du Mont-Valérien, commonly called Foundation Foch. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|