|

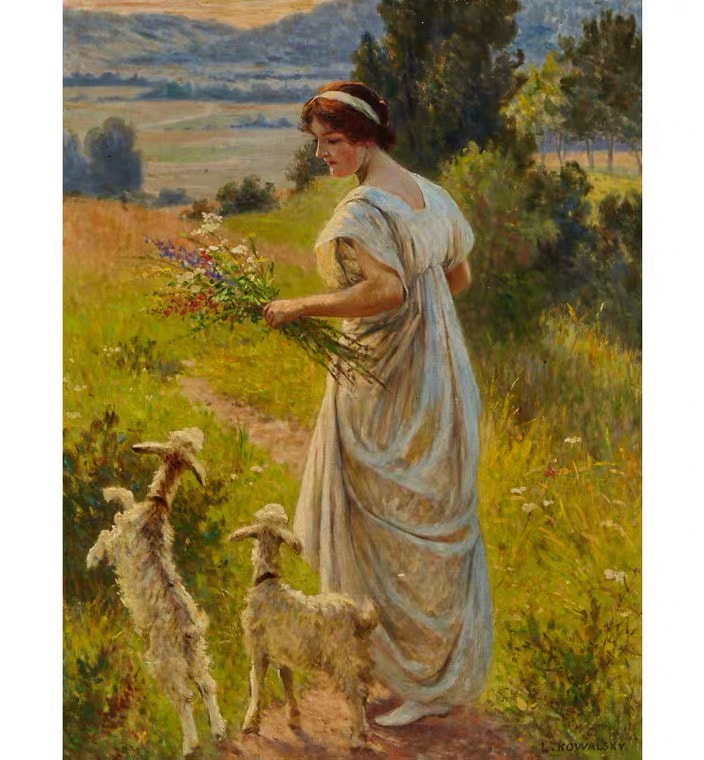

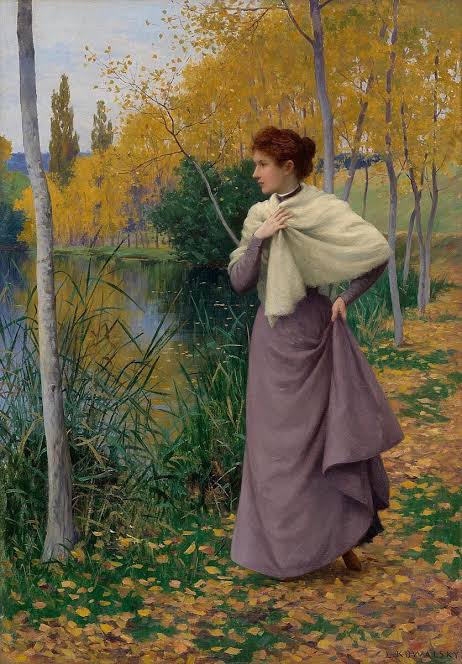

Léopold-François Kowalsky, né le 8 décembre 1856 à Paris et mort le 13 juillet 1931 à Hardencourt-Cocherel, est un peintre français. BiographyLéopold Franz Kowalski was born in France. He first studied at Ecole des Beaux-Arts de Paris. in 1878, then went to académie Julian. In 1881, he first exhibited his art works in Parisian salon and became member of French Artist Association. In 1886, while on a trip to New York, he married Marie Joséphine Jeanne Dantare(born in 1860). Léopold-François Kowalsky was known for his canvases depicting genre scenes, figures and landscapes. In 1931, he died at the age of 74, and was buried beside his son Maurice Léopold. BiographieLéopold-François Kowalsky est le fils de Jean-Léon Kowalsky, marchand de pierres y fines, et de Fanny Carnesecchi.

Élève de Jacques Pilliard et Henri Lehmann, il intègre les Beaux-Arts de Paris en 1878, puis l'académie Julian. Il débute au Salon parisien en 1881 et devient membre de la Société des artistes français. En 1886, lors d'un séjour à New York il épouse Marie Joséphine Jeanne Dantare (née à Dijon en 1860). Il obtient une mention honorable en 1890 et une médaille de troisième classe en 1891. Au Salon de 1905, il propose le portrait de la jeune milliardaire, Mlle Disston. En 1912, il emménage dans l'Eure; sa proche famille sera dès lors le seul sujet de sa production artistique. Son fils Maurice Léopold (1883-1915) engagé dans les combats de la première Guerre Mondiale est mort pour la France. Il meurt à l'âge de 74 ans. Il est inhumé auprès de son fils Maurice Léopold à Hardencourt-Cocherel.

0 Comments

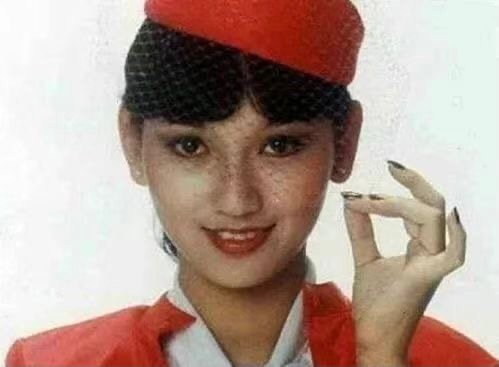

Angie Chiu (Chinese: 趙雅芝; pinyin: Zhào Yǎzhī; born 15 November 1954) is a Hong Kong actress, and was the third runner up in the 1973 Miss Hong Kong pageant. 趙雅芝(英語:Angie Chiu Ngar Chi,1954年11月15日—),香港女演員,1970至80年代無綫電視「四大花旦」之一。趙雅芝以俏麗脫俗的古裝扮相稱著,曾主演多套經典香港電視劇與臺灣電視劇。其中較為著名的作品除了金庸小說改編劇 《倚天屠龍記》、《刀神》之外,趙雅芝在《上海灘》的角色「馮程程」、古龍小說改編劇《楚留香》系列角色「蘇蓉蓉」、語言學家林語堂名著改編劇京華煙雲的「姚木蘭」、戲說乾隆系列三個單元大相徑庭的角色「程淮秀」、「沈芳」、「金無箴」,均在華人地區受到极大矚目。 1992年,她在台灣電視公司《新白娘子傳奇》片中演出的「白素貞」亦掀起「白蛇熱」。2000年以後,趙雅芝投入多項公益活動,包括向汶川大地震、2011年東日本大震災等捐款,拜訪慰助災區,投入教育與飲水工程勸募,並曾當選歷屆香港小姐組成之慈善團體慧妍雅集會長(2010年 -2012年)。積極投入社會慈善工作為她贏得了2007年華鼎獎公眾形象港台最佳影視女演員獎、與唐國強、彭麗媛、劉德華、梁朝偉等並列最受公眾尊敬表演藝術獎,2015年另獲得17屆華鼎獎中國電視劇傑出成就獎。 BiographyIn 1954, Angie Chiu was born in Hong Kong. In 1971, Chiu graduated from Shung Tak Catholic English College and later worked as a flight attendant at Japan Airlines. In 1973, Chiu participated in the first Miss Hong Kong contest organized by TVB and won the third runner-up. Chiu started her career as a flight attendant for Japan Airline. In 1973, Chiu participated in Miss Hong Kong Pageant. In 1970s, Chiu's acting career began. Chiu is most noted for her leading role in The Heaven Sword And Dragon Saber, Chor Lau Heung, The Bund, opposite Chow Yun-fat and Lui Leung-Wai. In 1975, Chiu married Wong Hon-wai (黃漢偉), a medical doctor. They had two children, Gary Wong (黃光宏) and Ronnie Wong (黃光宜). In 1983, Chiu divorced Wong Hon-wai. In 1984, Chiu married Melvin Wong, an actor. On 7 January 1986, their son Wesley Wong (黃愷傑) was born. He later became an actor. Chiu is a well known actress in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau and Mainland China. 生平1971年,趙雅芝畢業於天主教崇德英文書院,之後於日本航空公司擔任空中乘務員。1973年,趙雅芝參加無綫電視舉辦的首屆香港小姐競選,並獲得第四名。1976年,因嚮往演藝圈工作而辭去空勤一職,加入無綫電視戲劇組。 趙雅芝加入無線電視後,開始接拍多部電視劇。其中包括《乘風破浪》裡的施淑楓,《大報復》裡的韋婷,《大亨》裡的朱敏芝,《倚天屠龍記》裡的周芷若,《楚留香》裡的蘇蓉蓉,《上海灘》飾演馮程程。 她同时出演多部電影。1976年,出演電影《半斤八兩》女主角,1979年,趙雅芝與狄龍合作電影《教頭》、與爾冬升合作電影《英雄無淚》、拍攝許鞍華導演的經典電影《瘋劫》。其後,亦在《彈指神功》及《風鈴中的刀聲》中飾演蓉蓉一角。 1978年趙雅芝與鄭少秋合演《倚天屠龍記,使趙雅芝開始走紅。《倚天屠龍記》是趙雅芝的第一部古裝武俠劇, 讓香港觀眾看到她美麗的古裝扮相。過後趙雅芝演不少古裝武俠劇,例如1979年《楚留香》、《刀神》、1981年《飛鷹》使不少觀眾公認她為當時「古裝第一美人」的稱號。其中趙雅芝與鄭少秋主演的1981年《 飛鷹》讓趙雅芝獲得2011年新加坡新传媒华语剧50年《古裝美女第一名》。趙雅芝也憑著在1979年《楚留香》和1980年與的精湛演出更讓她在港台東南亞紅透半邊天,達到演藝生涯的高峰。 至1980年代她仍連續成為無線電視旗下當家花旦。1981年,趙雅芝生完孩子後,客串青春電影《失業生》。 1985年,趙雅芝與無線電視合約期滿,因為家中有三個兒子需要全心撫養,趙雅芝選擇退隱江湖,結束與無線電視12年之賓主關係。 在台灣製作人的優厚待遇和配合寒暑假檔期的情況下,她偶爾會去台灣拍戲,拍戲貴精不貴多,演出過《京華煙雲》、《戲說乾隆》、《新白娘子傳奇》等戲劇。 2002年,趙雅芝重返無線電視,首部回歸作為《西關大少》,再次與劉松仁合作,飾演善良慈祥秘書「伍玉卿」一角。2003年,趙雅芝拍攝完畢後,隨即離開無線電視。偶爾於無線大型節目以嘉賓出場,近期,趙雅芝在無線大型節目以嘉賓出場的節目為《萬千星輝頒獎典禮2009》以及《2012年度香港小姐競選》。 2013年,獲導演王晶邀請特別客串其監製家庭倫理大作《風雲天地》(前名《縱橫天地》)。 2016年,趙雅芝以61歲之齡參加湖南衛視年度真人秀《偶像來了第二季》,與劉嘉玲、莫文蔚、陳喬恩、謝娜及江一燕等人合作,其中更與劉嘉玲成為節目中的重點女神。 趙雅芝於1975年與醫師黃漢偉結婚,1983年離婚,取得兩子(兄黃光宏、弟黃光宜)的監護權。1984年,她與男演員(現為律師)黃錦燊在美國結婚,兩人育有一子黃愷傑。長子黄光宏在一家香港報社工作,二子黄光宜在加拿大讀書,三子黃愷傑就讀於北京電影學院。

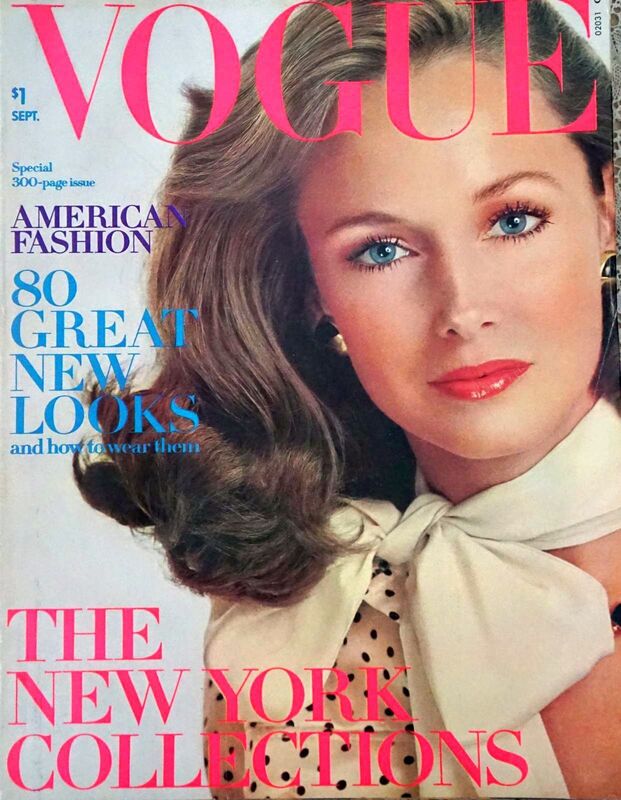

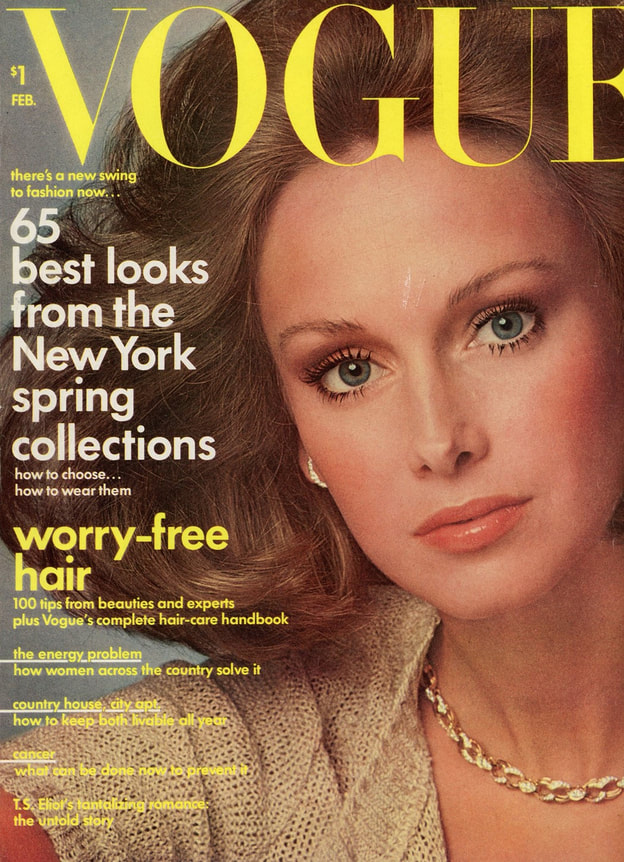

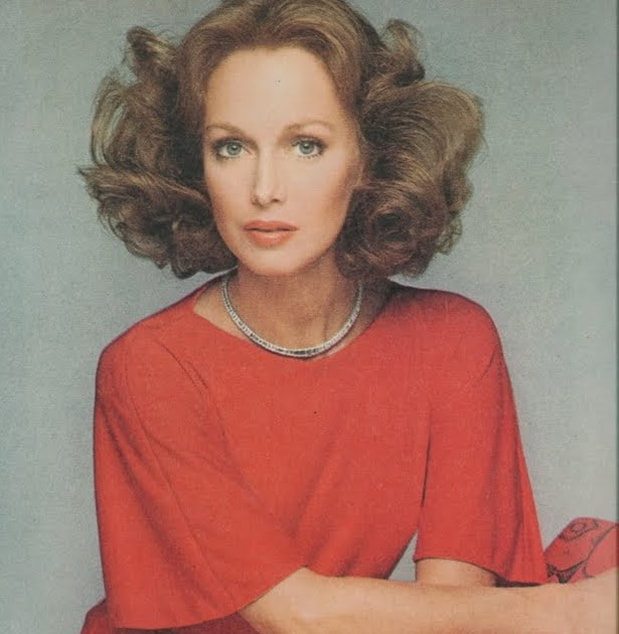

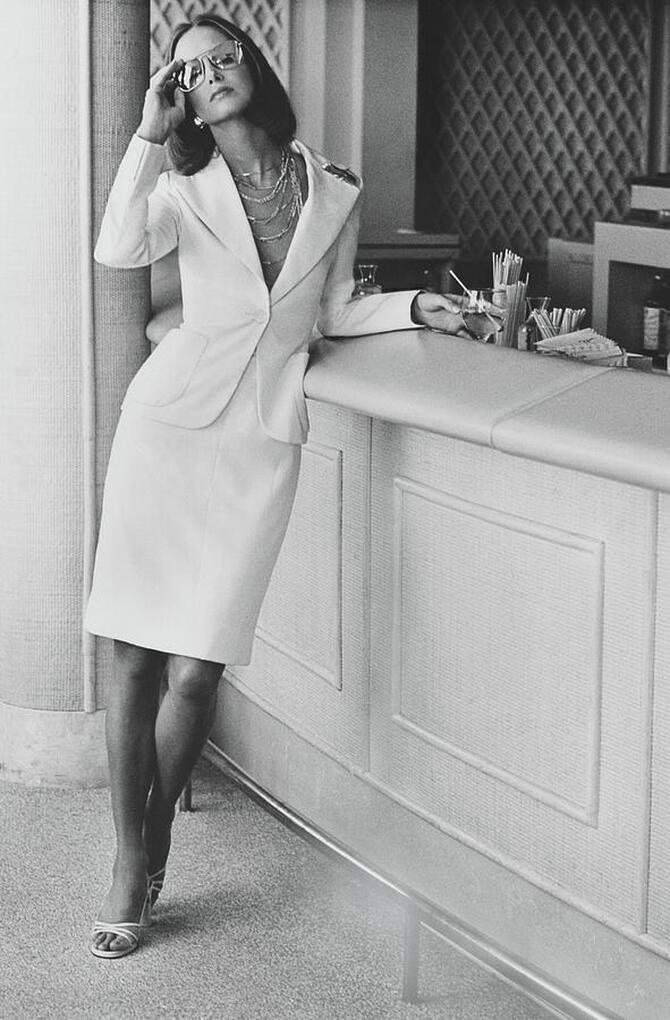

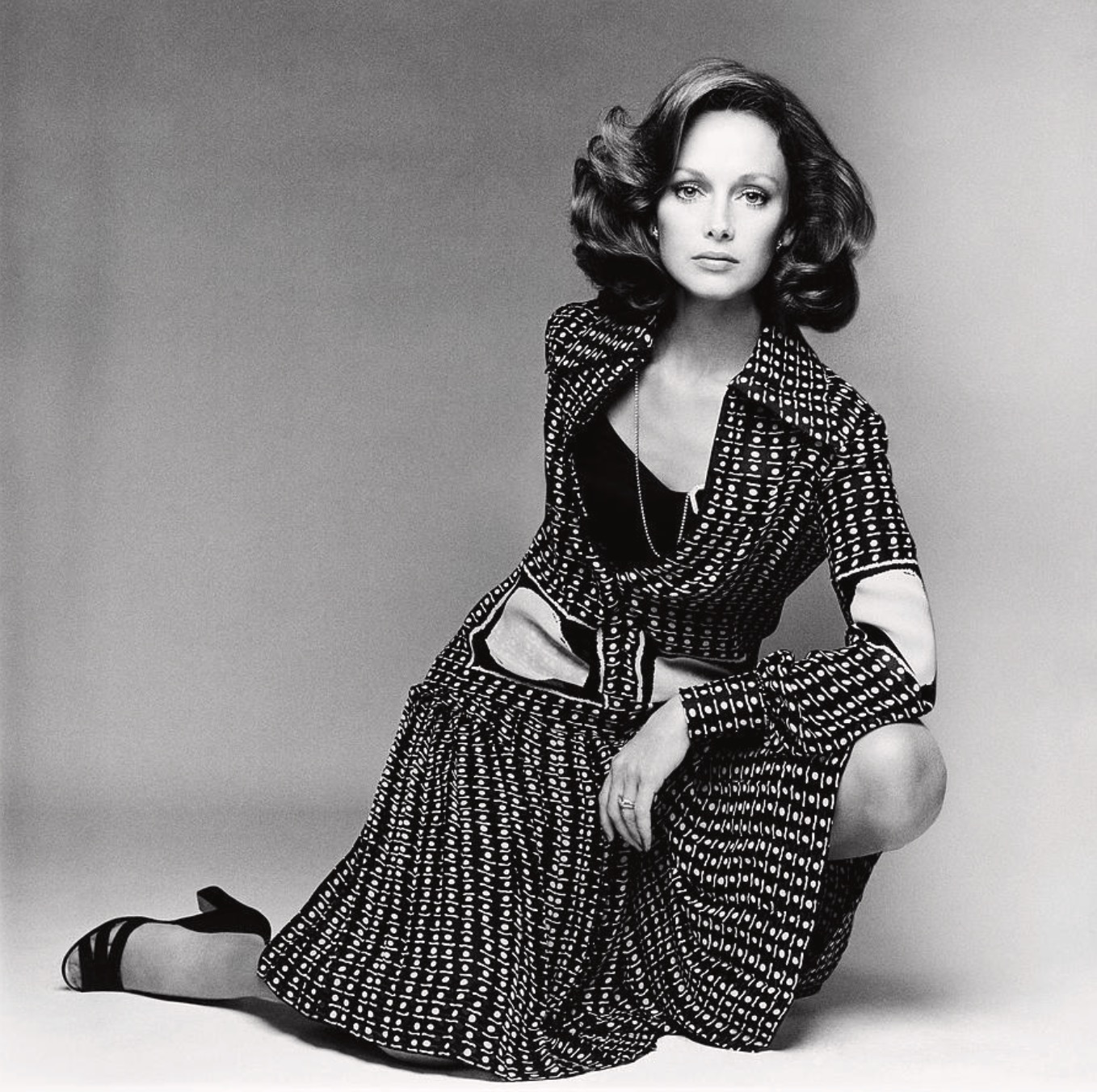

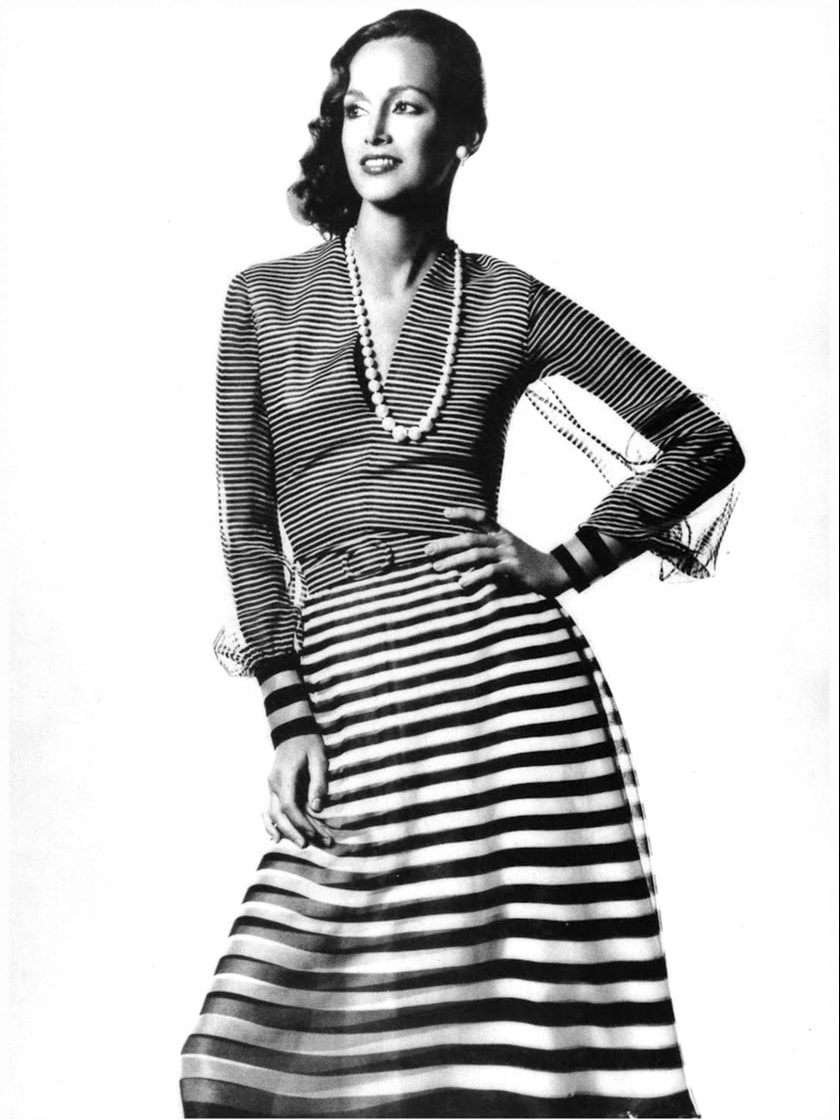

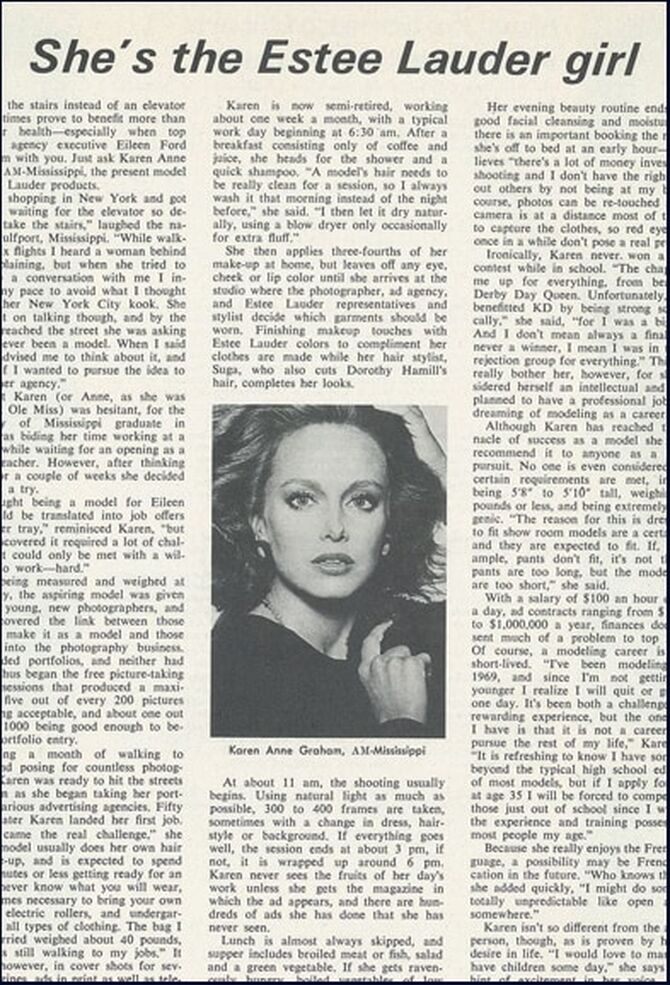

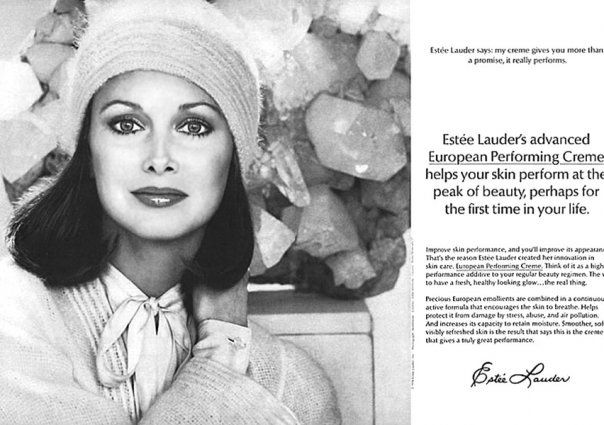

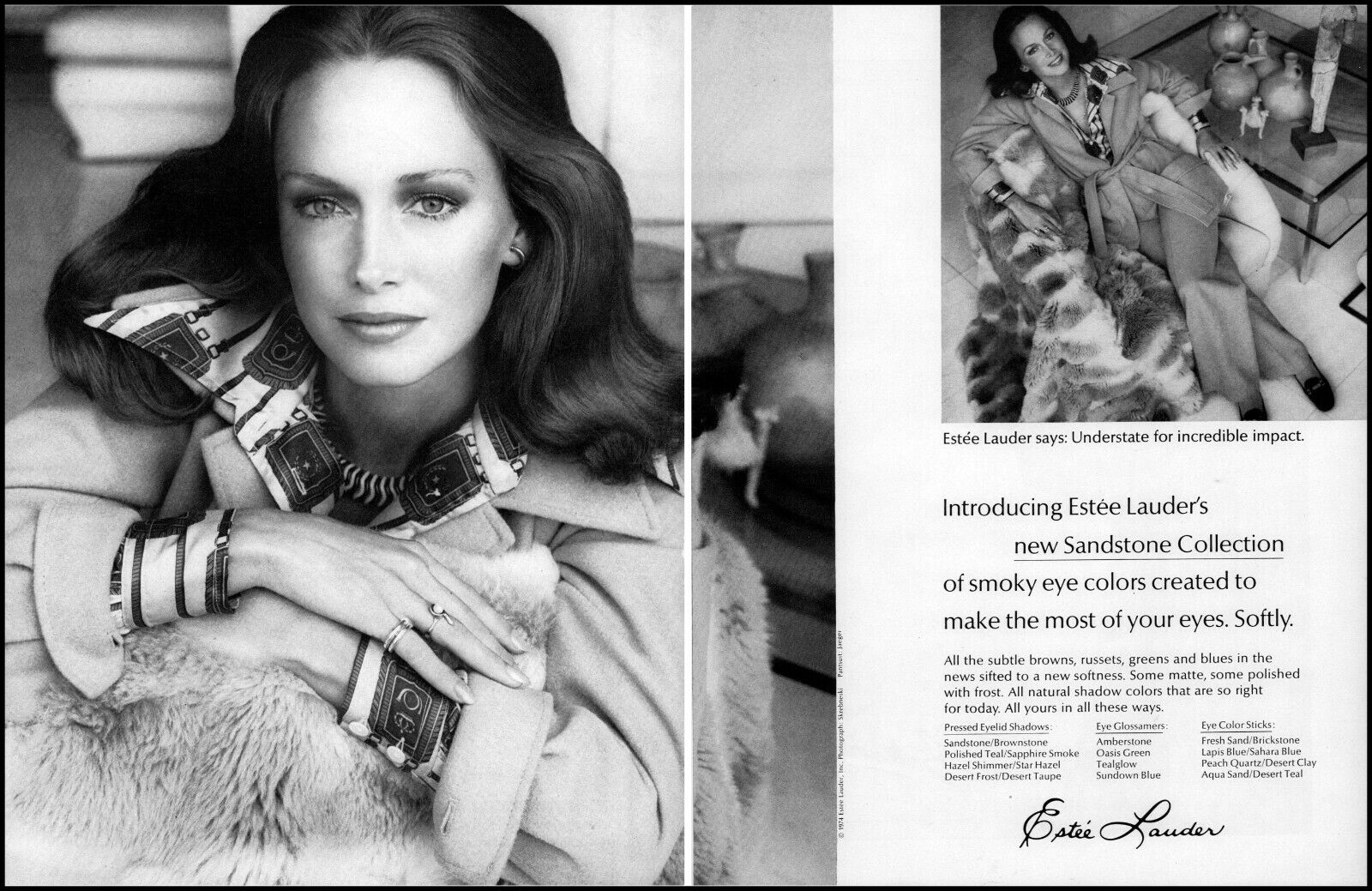

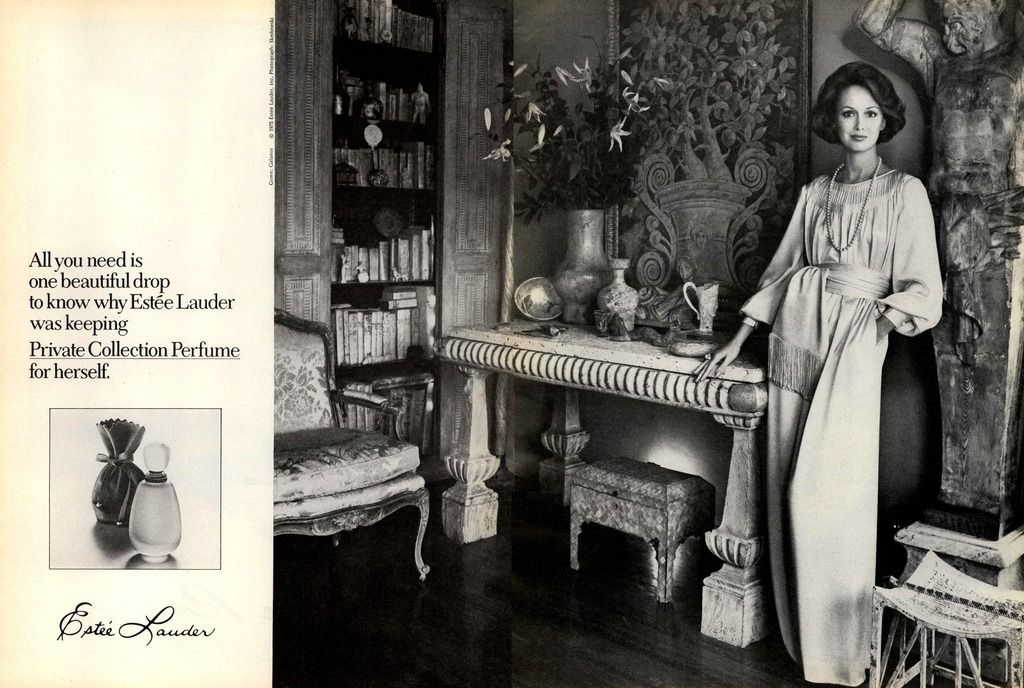

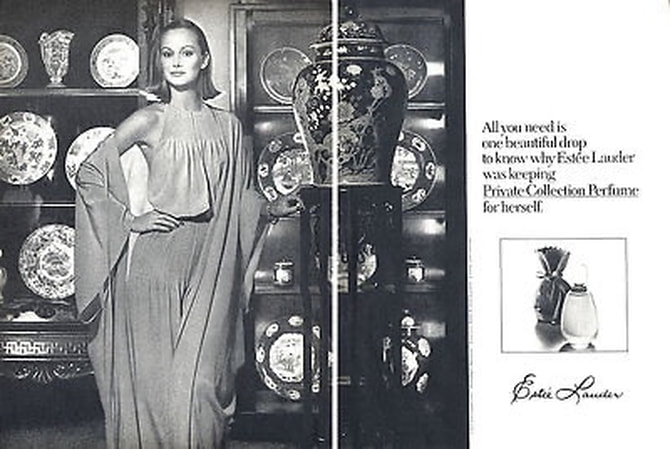

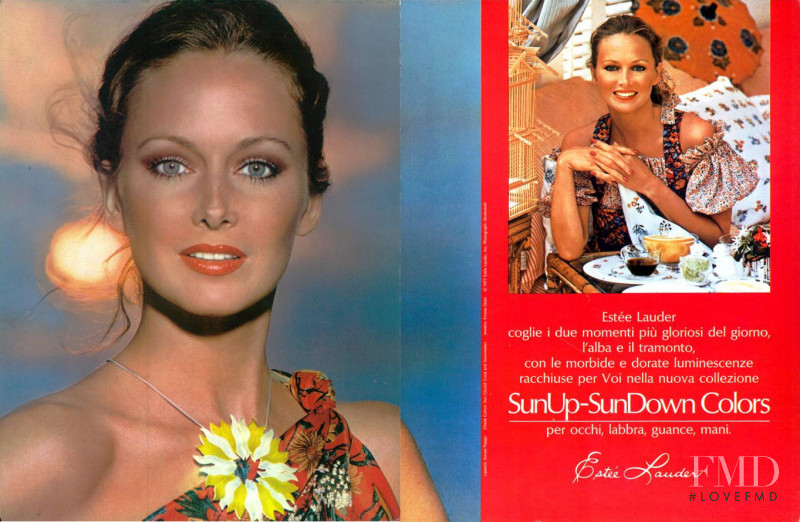

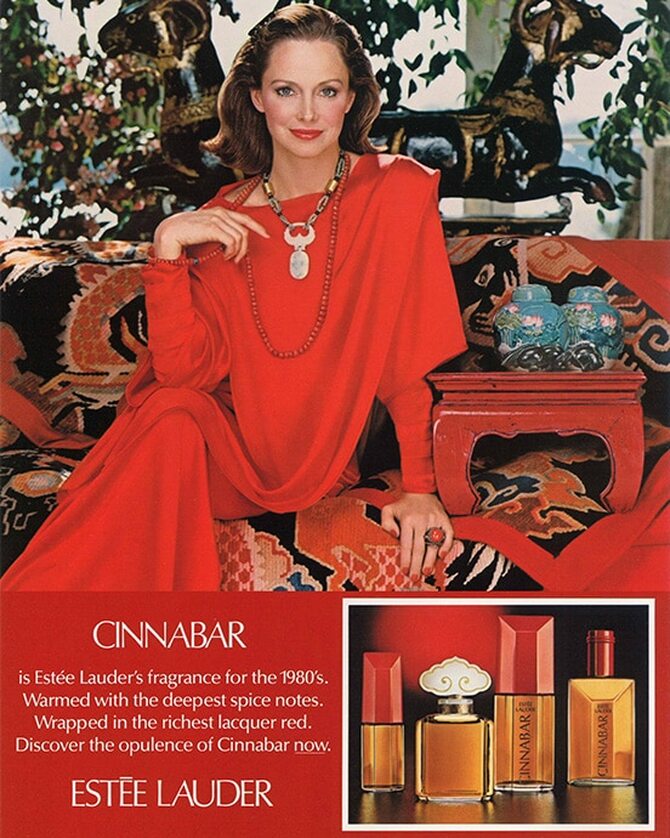

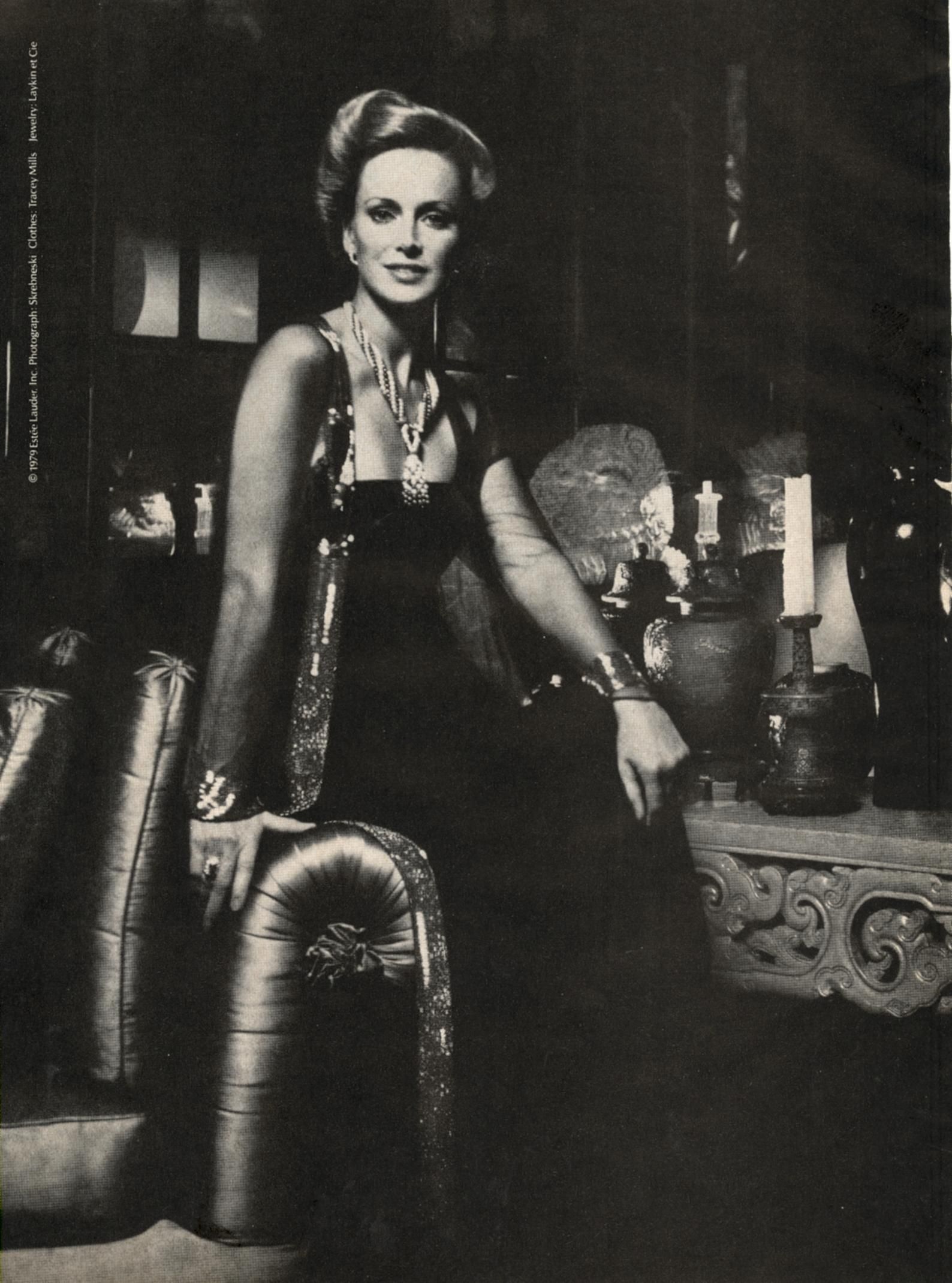

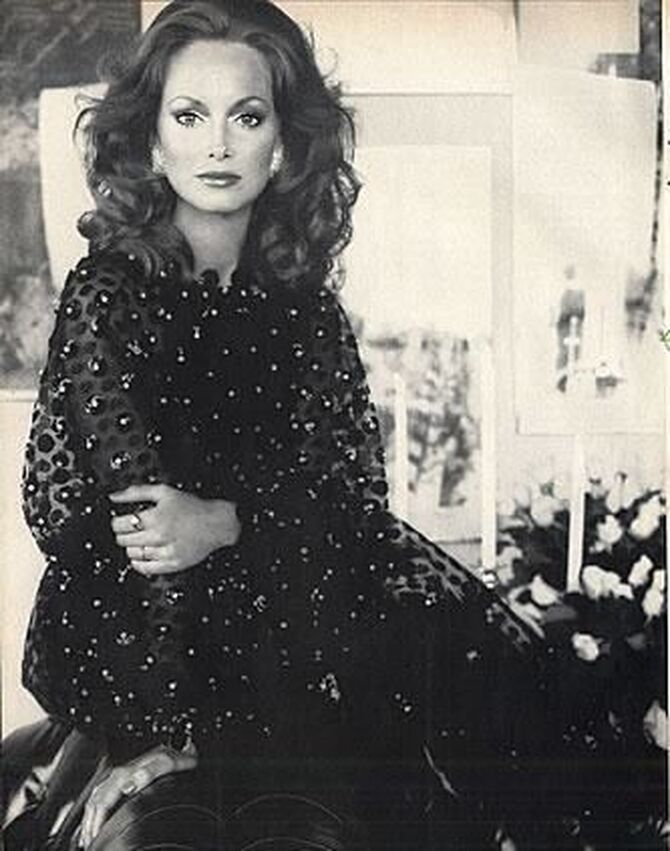

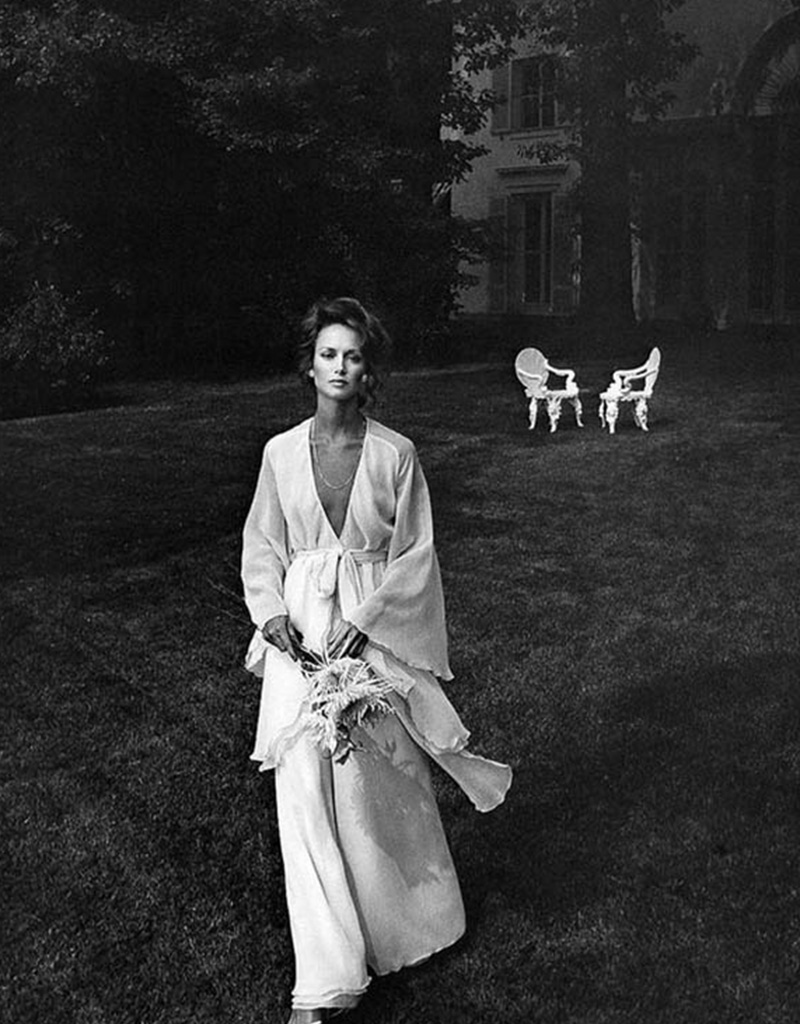

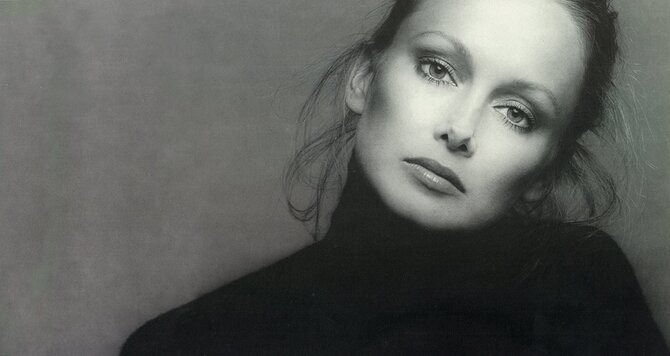

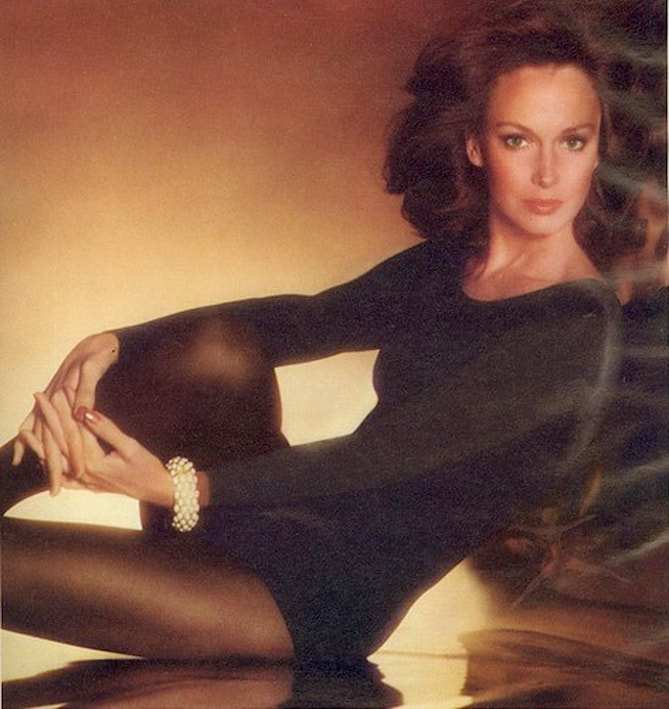

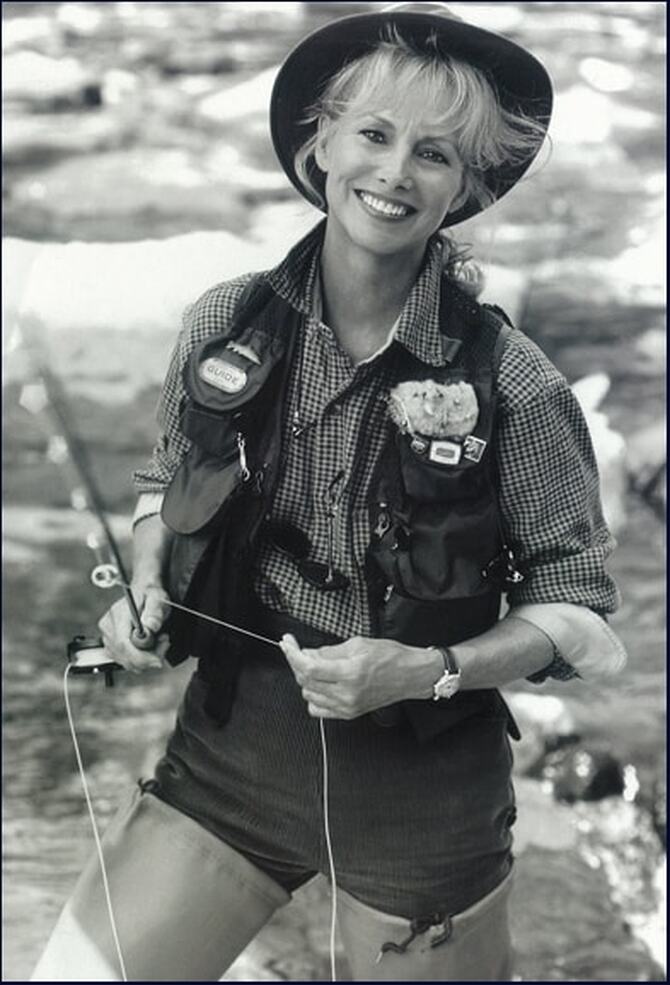

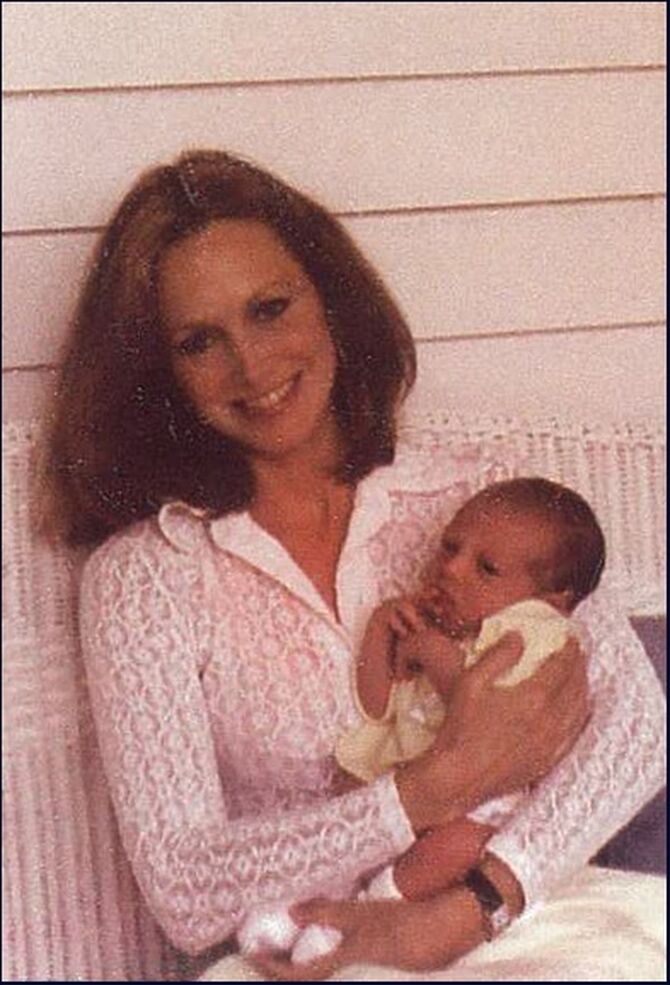

Karen Graham was born in Gulfport, Mississippi in 1945. After college, she moved to New York City to pursue career as a French-language high school teacher. In 1969, Karen Graham met model agency owner Eileen Ford while shopping at Bonwit Teller in Manhattan. Ford suggested that she become a model and shared her business card. This interaction launched Graham’s modelling career. Graham's early work included a photo shoot for Irving Penn. Penn saw potential in Graham and wanted to include her in a shoot for Vogue. The photographer insisted that the model be featured in the fashion spread, despite resistance from Vogue’s editor-in-chief at the time, Diana Vreeland, due to Graham’s small stature. Following this, Karen Graham was featured on the cover of Vogue magazine 20 times between 1970 and 1975. Graham's first notable modelling job was an Estee Lauder advertising campaign. The company began employing her intermittently during 1970 and 1971 to appear in their print ads. She worked with Chicago photographer Victor Skrebneski. By 1973, she had become Estee Lauder's exclusive spokesmodel. It was a job she would do for the rest of the decade, appearing in print and television ads that presented her in tasteful, elegant, generously appointed tableaux - a parlor, a drawing room, a veranda - to represent the image the Estee Lauder company created for itself. In these ads, Graham was never identified by name, which Estee Lauder herself frankly admitted was deliberate. Mrs. Lauder did not want to dilute attention on the product by focusing more attention on the model in the ads. Many people, unfamiliar with the fashion and modeling world, thought Graham was, in fact, Mrs. Lauder. Ironically, the ads reflected Mrs. Lauder's idea of a woman of taste and sophistication. Victor Skrebneski was happy to oblige, decorating his sets with Chinese vases, Pablo Picasso ceramics, and well-stocked bookshelves. Because the Lauder company aimed its products at upper-income women, at expensive prices, the ads had to project luxury. Various props were used - dolls, horses, and, curiously, a framed photograph of Nicholas II, the last czar of Russia, in a 1981 ad. The ad campaigns were meant to project traditional, Old-World elegance. An exception was an ad campaign for the Lauder company's "Swiss age-controlling skincare program," in which Skrebneski photographed Graham standing among edged cylinders in a futuristic tableau and wearing her hair back, adorned with what looked like a plastic stereo headset and worn as if it were a space-age tiara. Karen Graham was joined by model Shaun Casey in the Estee Lauder campaign in 1981, and for the next four years, the Lauder company was thus represented by two spokesmodels. Graham quit in 1985 when she turned 40; as she told People magazine in 2000, she decided to leave modeling while she was still on top. Shaun Casey only briefly appeared in magazine advertisements before being fired and replaced with a future news anchorwoman Willow Bay. Graham remained in New York City for another six years before she moved to Rosendale, New York, where she pursued her hobby, fly fishing. She had taken up the sport in the seventies after her brother had given everyone in her family a fly rod. Her passion for fly fishing led to a second career as a fly-fishing school operator and instructor, when she co-founded, with veteran fisherman Bert Darrow, Fly Fishing With Bert and Karen. In 1974, Graham was engaged to David Frost but married Chicagoan, Delbert W. Coleman, casino owner, who ran the Stardust Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada. She has a son, Graham Douglas Mavar with Sam Mavar. In 1999, she returned to modeling for Estee Lauder's "Resilience Lift" face cream, aimed at older women and designed to help female skin reproduce the skin nutrients that prevent wrinkles. Graham was happy to return to modeling for the campaign, which lasted for a few years, and Victor Skrebneski returned to shoot the print ads for the Lauder company after leaving in 1993. She now lives in the foothills of North Carolina. In addition to fly fishing, she takes a great interest in horseback riding.

|

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|