|

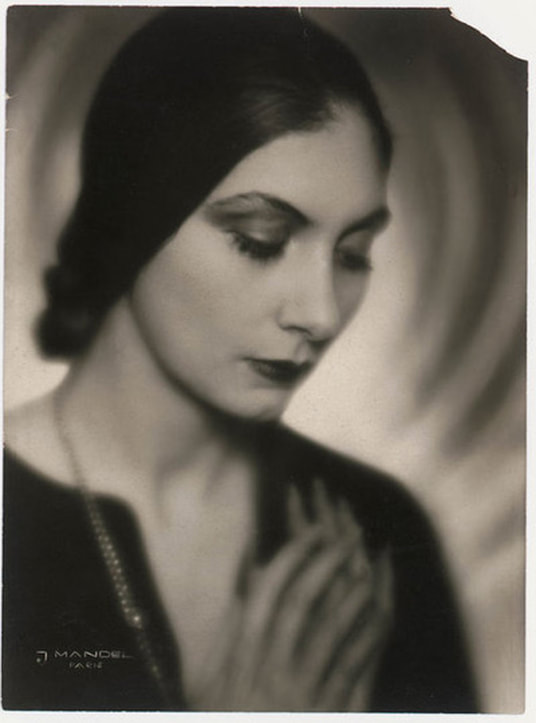

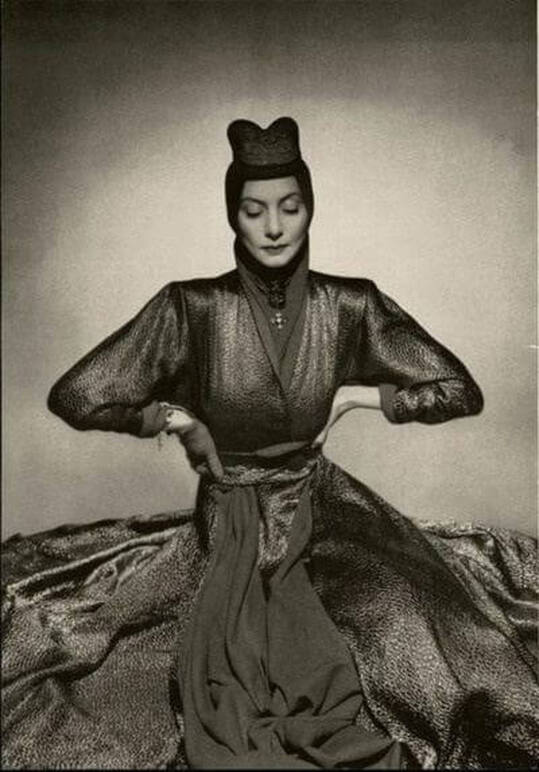

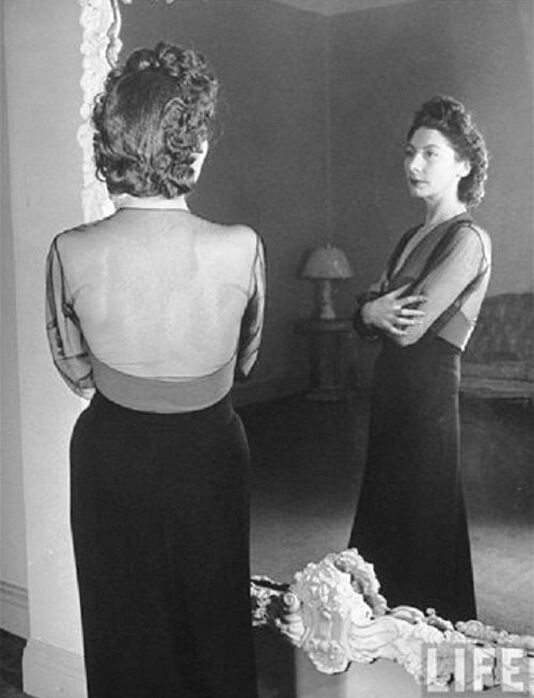

Valentina Nicholaevna Sanina Schlee (1 May 1899 – 14 September 1989), simply known as Valentina, was a Ukrainian émigrée fashion designer and theatrical costume designer active from 1928 to the late 1950s. BiographyValentina Schlee was born and raised in Kiev, Russian Empire (modern-day Ukraine). She was studying drama in Kharkov at the outbreak of the October Revolution in 1917. She met her Russian financier husband, George Schlee (Who is best known for his 20-year friendship with Swedish film star Greta Garbo.), at the Sevastopol railway station as she was fleeing the country with her family jewels; there is some question as to whether they were legally wed. The Schlees arrived in New York City in 1923 and became prominent members of café society during the Roaring Twenties. Valentina looked distinct for her clothes and style at the time because she appeared in floor-lengths and cover-ups while other women wore short skirts and low-neck dresses." Valentina Schlee opened a small couture dress house, Valentina's Gowns on Madison Avenue in 1928. Her first stage commission was costumes for Judith Anderson in 1933's Come of Age. The costumes were better received than the play, and established her reputation as a designer for the stage. Schlee dressed such actresses of the era as Lynn Fontanne, Katharine Cornell, Greta Garbo, Gloria Swanson, Gertrude Lawrence, and Katharine Hepburn. Her Broadway successes included the costumes for the play The Philadelphia Story. Valentina also dressed prominent New York society women including members of the Whitney and Vanderbilt families. In 1950 Valentina also introduced a perfume, "My Own".  GRETA GARBO navy blue and black dress: An early 1950s dress by Valentina in navy blue satin and wool jacquard with a black abstract pattern. The dress has a V-neck with notched collar, single button closure on front of dress and zipper at back. The skirt has some box pleating. Accompanied by a structured matching belt embellished with a bow.  GRETA GARBO green wool dress designed by Valentina: a dress in pale pistachio green wool with three-quarter-length sleeves, two pockets at front of skirt. Collar points are tacked to interior of dress to create a modified mandarin collar with ties. Hook and eye closure at waist and collar. Accompanied by matching tie belt. Schlee's made-to-measure, flowing styles combined the intricate bias cut of Madeleine Vionnet and the grace of gowns by Alix Gres. "Simplicity survives the changes of fashion," she said in the late 1940s. "Women of chic are wearing now dresses they bought from me in 1936. Fit the century, forget the year." Schlee was a skilled self-promoter. She modeled her own designs and rarely let her dramatic, elegant air of self-possession falter. Schlee was always impeccably turned out, earning her a mention on the International Best Dressed List. Valentina Schlee used to be Greta Garbo's close friend, and the two women lived in the same apartment building in New York City. After Valentina's husband George Schelee left her for Garbo, they were not friends anymore but remained neighbors. George Schlee died in 1964 while traveling with Greta Garbo in Paris. Afterwards, Valentina and Garbo were not on speaking terms anymore and the two women had an elaborate schedule set up so that they would never run into each other in the lobby of their building. Valentina Schlee closed her fashion house in the late 1950s. She died of Parkinson's disease in 1989, aged 90.

In 2009, Valentina: American Couture and the Cult of Celebrity, a large retrospective exhibition opened at the Museum of the City of New York. It was the first exhibition to trace Valentina's career and featured never-before-exhibited gowns, accessories, photographs, and printed matter from the collections of the Museum of the City of New York, the Valentina family, and other major collections.

0 Comments

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (22 April [O.S. 10 April] 1899 – 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (Владимир Сирин), was a Russian-American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Born in Russia, he wrote his first nine novels in Russian (1926–1938) while living in Berlin. He achieved international acclaim and prominence after moving to the United States and beginning to write in English. Nabokov became an American citizen in 1945, but he and his wife Vera returned to Europe in 1961, settling in Montreux, Switzerland. Nabokov's Lolita (1955) was ranked fourth in the list of the Modern Library 100 Best Novels in 2007; Pale Fire (1962) was ranked 53rd on the same list; and his memoir, Speak, Memory (1951), was listed eighth on publisher Random House's list of the 20th century's greatest nonfiction. He was a seven-time finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction. Nabokov was also an expert lepidopterist and composer of chess problems. He describes the process of composing and constructing in his memoir: "The strain on the mind is formidable; the element of time drops out of one's consciousness". To him, the "originality, invention, conciseness, harmony, complexity, and splendid insincerity" of creating a chess problem was similar to that in any other art. BiographyNabokov was born on 22 April 1899 (10 April 1899 Old Style) in Saint Petersburg to a wealthy and prominent family of the Russian nobility. His family traced its roots to the 14th-century Tatar prince Nabok Murza, who entered into the service of the Tsars, and from whom the family name is derived. His father was Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov (1870–1922), a liberal lawyer, statesman, and journalist, and his mother was the heiress Yelena Ivanovna née Rukavishnikova, the granddaughter of a millionaire gold-mine owner. His father was a leader of the pre-Revolutionary liberal Constitutional Democratic Party, and wrote numerous books and articles about criminal law and politics. His cousins included the composer Nicolas Nabokov. His paternal grandfather, Dmitry Nabokov (1827–1904), was Russia's Justice Minister during the reign of Alexander II. His paternal grandmother was the Baltic German Baroness Maria von Korff (1842–1926). Through his father's German ancestry, Nabokov was related to the composer Carl Heinrich Graun (1704–1759). Vladimir was the family's eldest and favorite child, with four younger siblings: Sergey (1900–45), Olga (1903–78), Elena (1906–2000), and Kirill (1912–64). Sergey was killed in a Nazi concentration camp in 1945 after publicly denouncing Hitler's regime. Elena, who in later years became Vladimir's favorite sibling, published her correspondence with him in 1985. She was an important source for later biographers of Nabokov. Nabokov spent his childhood and youth in Saint Petersburg and at the country estate Vyra near Siverskaya, south of the city. His childhood, which he called "perfect" and "cosmopolitan", was remarkable in several ways. The family spoke Russian, English, and French in their household, and Nabokov was trilingual from an early age. He related that the first English book his mother read to him was Misunderstood (1869) by Florence Montgomery. Much to his patriotic father's disappointment, Nabokov could read and write in English before he could in Russian. In his memoir Speak, Memory, Nabokov recalls numerous details of his privileged childhood. His ability to recall in vivid detail memories of his past was a boon to him during his permanent exile, providing a theme that runs from his first book Mary to later works such as Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle. While the family was nominally Orthodox, it had little religious fervor. Vladimir was not forced to attend church after he lost interest. Nabokov's adolescence was the period in which he made his first serious literary endeavors. In 1916, he published his first book, Stikhi ("Poems"), a collection of 68 Russian poems. That same year, Nabokov inherited the estate Rozhdestveno, next to Vyra, from his uncle Vasily Ivanovich Rukavishnikov. He lost it in the October Revolution one year later; this was the only house he ever owned. After the 1917 February Revolution, Nabokov's father became a secretary of the Russian Provisional Government in Saint Petersburg. After the October Revolution, the family was forced to flee the city for Crimea, where Nabokov's father became a minister of justice in the Crimean Regional Government. After the withdrawal of the German Army in November 1918 and the defeat of the White Army (early 1919), the Nabokovs sought exile in western Europe, along with many other Russian refugees. They settled briefly in England, where Vladimir enrolled in Trinity College of the University of Cambridge, first studying zoology, then Slavic and Romance languages. Nabokov later drew on his Cambridge experiences to write several works, including the novels Glory and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight. In 1920, Nabokov's family moved to Berlin, where his father set up the émigré newspaper Rul' ("Rudder"). Nabokov followed them to Berlin two years later, after completing his studies at Cambridge. In March 1922, Nabokov's father was fatally shot in Berlin by Russian some monarchists as he was trying to shield the real target, Pavel Milyukov, a leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party-in-exile. Nabokov featured this mistaken, violent death repeatedly in his fiction, where characters would meet their deaths under accidental terms. Shortly after his father's death, Nabokov's mother and sister moved to Prague. Nabokov stayed in Berlin. He wrote and published under the nom de plume V. Sirin (a reference to the fabulous bird of Russian folklore). To supplement his scant writing income, he taught languages and gave tennis and boxing lessons. In May 1923, he met Véra Evseyevna Slonim, a Russian-Jewish woman, at a charity ball in Berlin. They married in April 1925. Their only child, Dmitri, was born in 1934. In 1937, he left Germany for France, where his family followed him, finally settling in Paris which also had a Russian émigré community. In May 1940, the Nabokovs fled the advancing German troops, reaching the United States via the SS Champlain. Nabokov's brother Sergei did not leave France, and he died at the Neuengamme concentration camp on 9 January 1945. The Nabokovs settled in Manhattan and Vladimir began volunteer work as an entomologist at the American Museum of Natural History. Nabokov's interest in entomology had been inspired by books of Maria Sibylla Merian he had found in the attic of his family's country home in Vyra. Throughout an extensive career of collecting he never learned to drive a car, and he depended on his wife Véra to take him to collecting sites. During the 1940s, as a research fellow in zoology, he was responsible for organizing the butterfly collection of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University. Nabokov joined the staff of Wellesley College in 1941 as resident lecturer in comparative literature. The position, created specifically for him, provided an income and free time to write creatively and pursue his lepidoptery. Nabokov is remembered as the founder of Wellesley's Russian Department. In September 1942 they moved to Cambridge, where they lived until June 1948. Following a lecture tour through the United States, Nabokov returned to Wellesley for the 1944–45 academic year as a lecturer in Russian. In 1945, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. He served through the 1947–48 term as Wellesley's one-man Russian Department, offering courses in Russian language and literature. After being encouraged by Morris Bishop, Nabokov left Wellesley in 1948 to teach Russian and European literature at Cornell University, where he taught until 1959. Nabokov's lectures at Cornell University, as collected in Lectures on Literature, reveal his controversial ideas concerning art. He firmly believed that novels should not aim to teach and that readers should not merely empathize with characters but that a 'higher' aesthetic enjoyment should be attained, partly by paying great attention to details of style and structure. He detested what he saw as 'general ideas' in novels, and so when teaching Ulysses, for example, he would insist students keep an eye on where the characters were in Dublin (with the aid of a map) rather than teaching the complex Irish history that many critics see as being essential to an understanding of the novel. Nabokov wrote Lolita while travelling on the butterfly-collection trips in the western United States that he undertook every summer. Véra acted as "secretary, typist, editor, proofreader, translator and bibliographer; his agent, business manager, legal counsel and chauffeur; his research assistant, teaching assistant and professorial understudy"; He called her the best-humored woman he had ever known. When Nabokov attempted to burn unfinished drafts of Lolita, Véra stopped him. In June 1953 Nabokov and his family went to Ashland, Oregon. There he finished Lolita and began writing the novel Pnin. After the great financial success of Lolita, Nabokov returned to Europe and devoted himself to writing. In 1961 he and Véra moved to the Montreux Palace Hotel in Montreux, Switzerland; he stayed there until the end of his life. From his sixth-floor quarters he conducted his business and took tours to the Alps, Corsica, and Sicily to hunt butterflies. He died on 2 July 1977 in Montreux. His remains were cremated and buried at the Clarens cemetery in Montreux. At the time of his death, he was working on a novel titled The Original of Laura. Véra and Dmitri, who were entrusted with Nabokov's literary executorship, ignored Nabokov's request to burn the incomplete manuscript and published it in 2009.

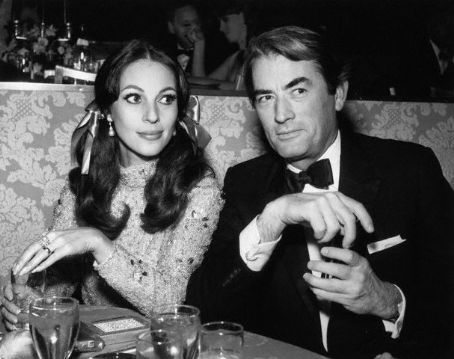

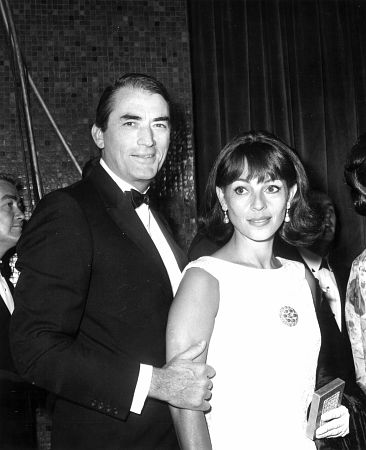

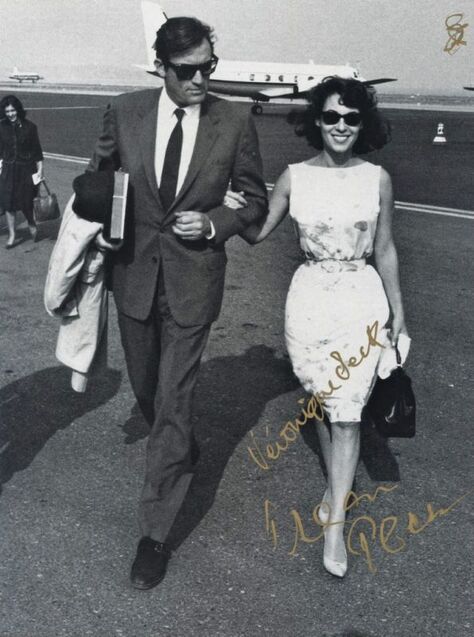

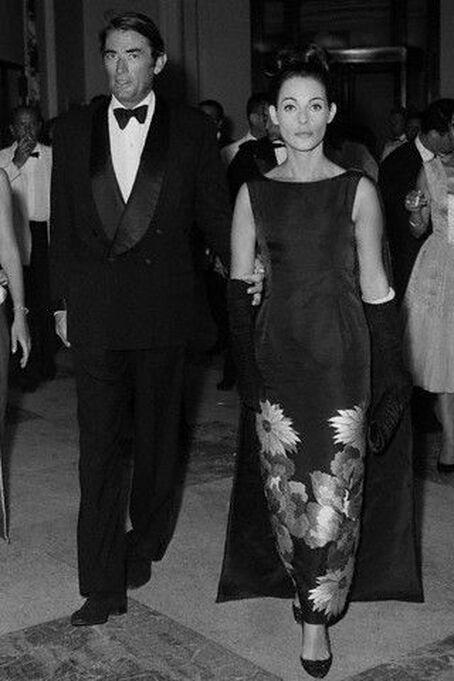

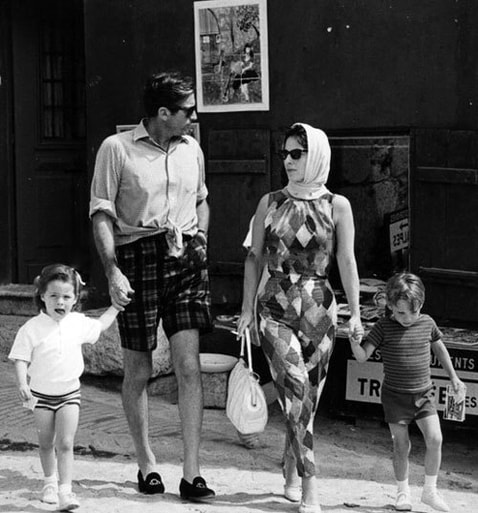

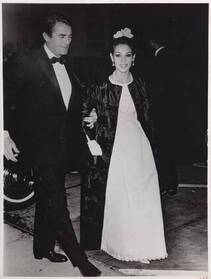

ProfileVeronique Peck (née Passani; 5 February 1932 – 17 August 2012) was a French-American arts patron, philanthropist and journalist. She was married to actor, political activist and philanthropist Gregory Peck from 1955 until his death in 2003. BiographyVeronique Passani was born in Paris, France; her mother was an artist and writer, while her father was an architect. She began her career as a journalist for France Soir, a French daily newspaper, and met Gregory Peck while conducting an interview for France Soir in 1953. The couple married on December 31, 1955, shortly after Peck's divorce from his first wife, Greta Kukkonen. Veronique Peck became a well-known philanthropist in Greater Los Angeles. She and her husband raised approximately $50 million for the American Cancer Society during the 1960s. The Los Angeles Times named her "Woman of the Year" in 1967. She also co-founded the Inner City Cultural Center, a theater group composed of members from different ethnic backgrounds, and the Los Angeles Music Center. Veronique Peck became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1976. Shortly after Gregory Peck's death in 2003, Veronique Peck took control of the Gregory Peck Reading Series. The series raises money on behalf of the Los Angeles Public Library through the collaboration of celebrities. Veronique Peck and her family attended a private White House screening of To Kill a Mockingbird(the film for which Gregory Peck was awarded Oscar) in 2012 with President Barack Obama to mark what would have been her late husband's 96th birthday. Veronique Peck died of a heart ailment at her home in Los Angeles, California on 17 August 2012, at the age of 80. She was survived by her daughter filmmaker Cecilia Peck, son Anthony Peck, three grandchildren, and her brother, Cornelius Passani. Further interestExhibition |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|

![Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (22 April [O.S. 10 April] 1899 – 2 July 1977)](/uploads/1/6/6/0/16606468/755729442_orig.jpg)