|

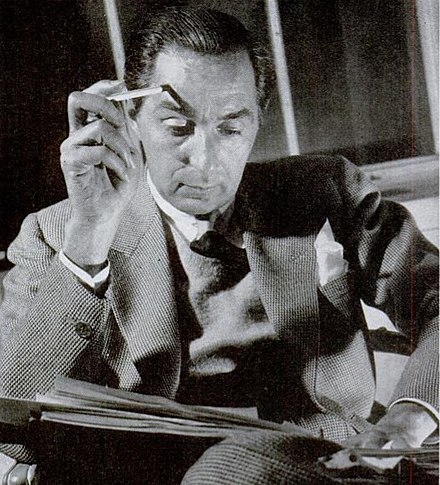

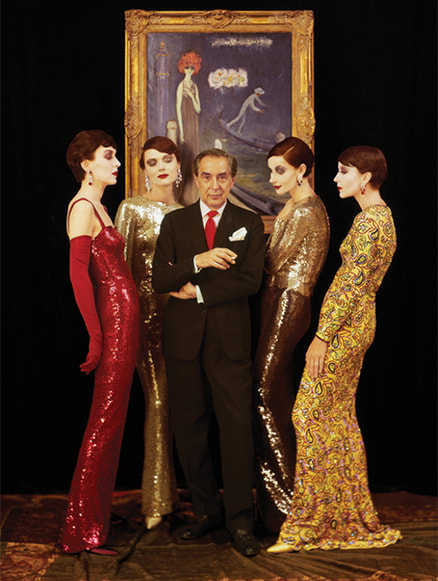

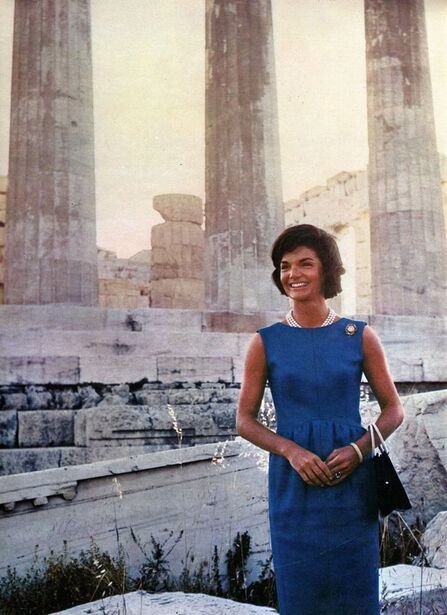

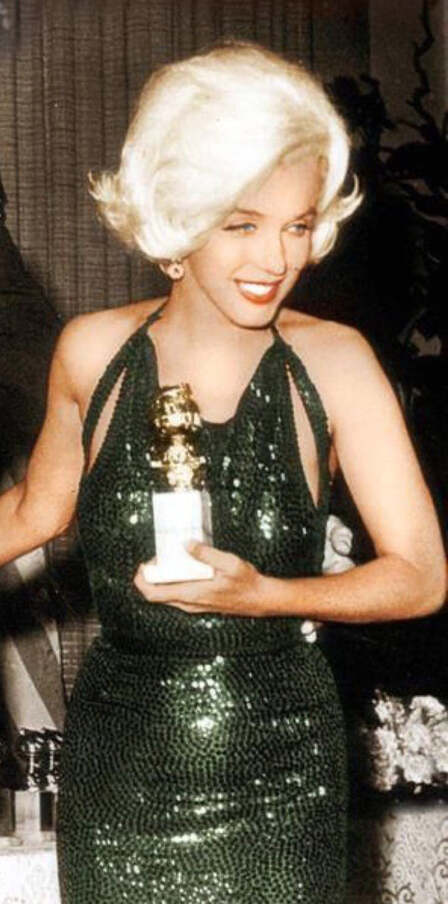

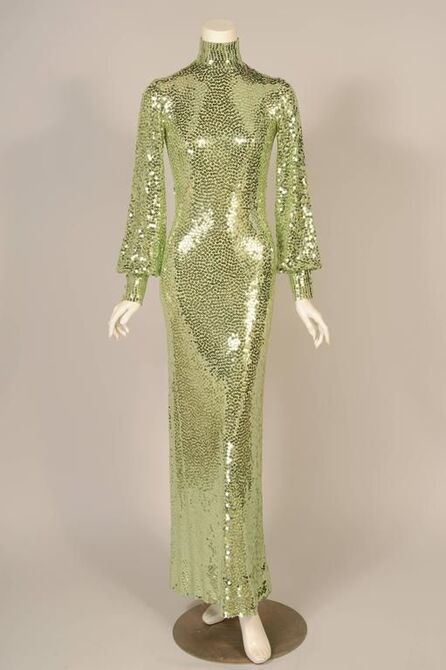

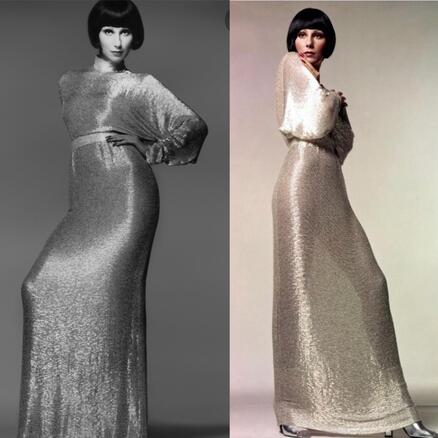

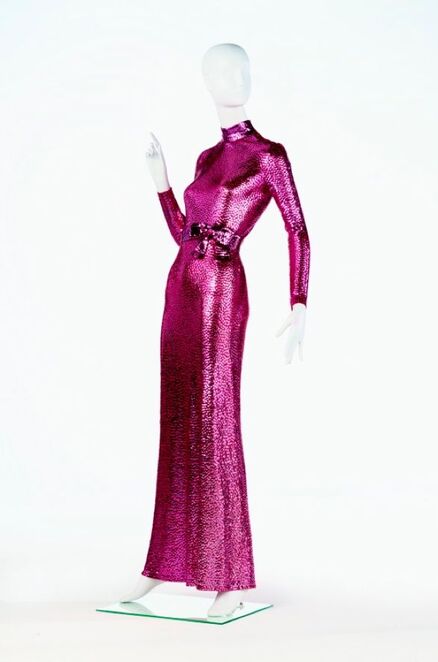

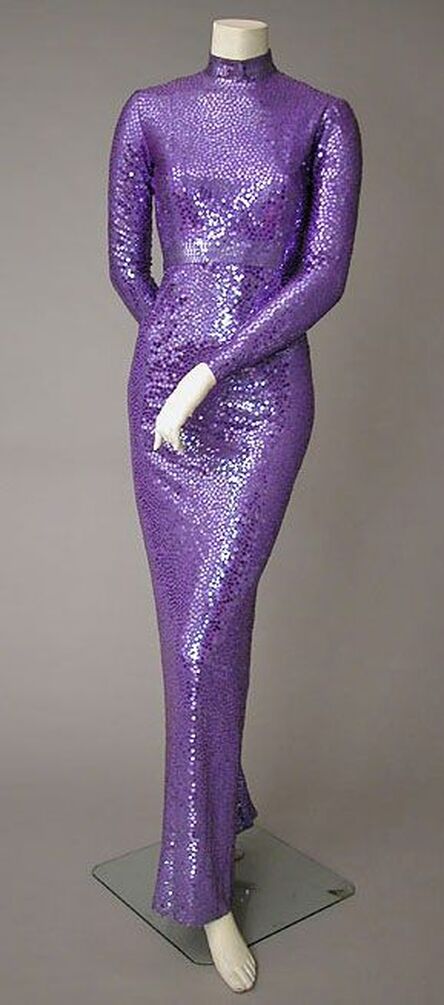

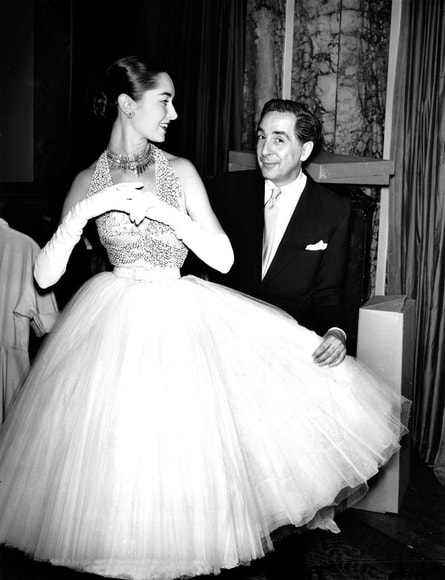

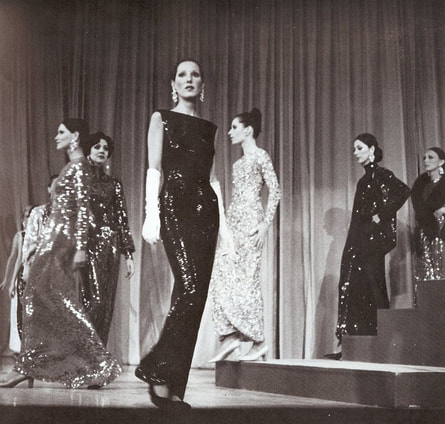

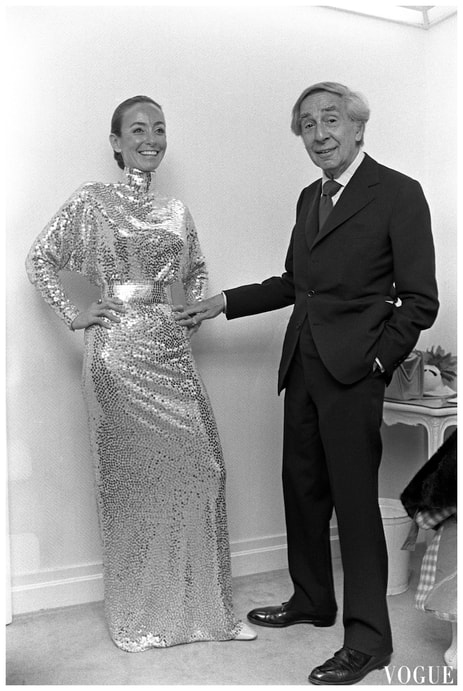

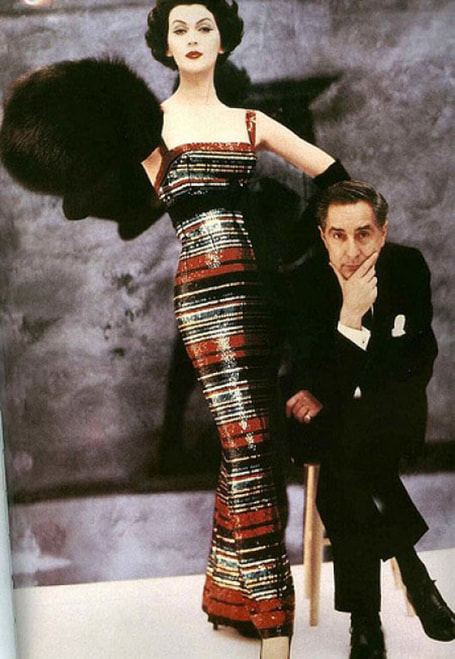

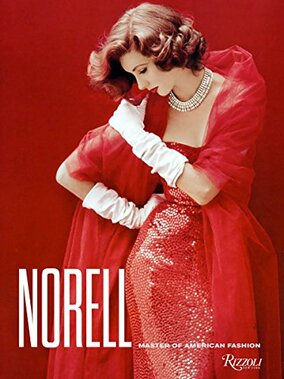

Norman David Levinson (April 20, 1900 – October 25, 1972) known professionally as Norman Norell, was an American fashion designer famed for his elegant gowns, suits, and tailored silhouettes. His designs for the Traina-Norell and Norell fashion houses became famous for their detailing, simple, timeless designs, and tailored construction. By the mid-twentieth century Norell dominated the American fashion industry and in 1968 he became the first American fashion designer to launch his own brand of perfume. Born in Noblesville, Indiana, Norell arrived in New York City in 1919, studied fashion illustration and fashion design at Parsons School of Design and Pratt Institute, and began his career designing costumes for silent-film stars. Before partnering with Anthony Traina to form the Train-Norell fashion house in 1941, Norell spent twelve years with Hattie Carnegie as a designer for her custom-order house. In the 1960s Norell became the sole owner of his own fashion house on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan. Norell amassed numerous private clients, including Hollywood stars and entertainers, wealthy socialites, and the wives of politicians and industrialists. On occasion, Norell created fashion designs for Hollywood films. Norell considered his greatest contribution to fashion was the inclusion of simple, no-neckline dresses. Norell was the first recipient of the American Fashion Critics' Award, later known as the Coty Award, the first designer inducted into the fashion industry critics' Hall of Fame, and a recipient of an International Fashion Award from the United Kingdom's Sunday Times. He is also among the first American fashion designers to be honored with a bronze plaque along New York City’s Seventh Avenue. Norell was a founder of the Council of Fashion Designers of America and a member of the Parsons School of Design's board of trustees, as well as a critic and teacher in the fashion design department at Parsons and a mentor to younger designers. The Pratt Institute awarded Norell an honorary fine arts degree. Norell continued to design fashions until his death in New York City in 1972. BiographyNorman David Levinson was born on April 20, 1900, in Noblesville, Indiana. He was the second son of Nettie and Harry Levinson. Norman's only sibling was an older brother named Frank. The family resided in the east side of a double home at 840 Cherry Street in Noblesville. His father, a haberdasher, ran a men's clothing store in Noblesville, but Norman later credited his mother with introducing him to fashion. Around 1905 Norman's father opened a men's hat store on Pennsylvania Street in Indianapolis, Indiana, and the family moved to Indianapolis about a year later. Frail and frequently ill in his early childhood, Norman recuperated in bed, amusing himself by drawing. Although his brother worked in the family's store from a young age and later managed the family's retail business, Norman preferred drawing and attending the theater. Because Norman's father advertised his hat shop in theater playbills, the family received free passes to attend the shows. Norman saw three or four theater performances a week and entertained himself by sketching costumes and theater sets. He attended a military school in Kentucky, and after a brief and miserable period at the school, Norman withdrew and returned to Indianapolis, but he had no interest in joining the family's clothing business. In 1919, at the age of nineteen, Norman traveled to New York City to study fashion illustration at Parsons School of Design. A year later he enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn to study fashion design. Around the same time, Norman adopted his professional surname of Norell. During the 1940s Norell told reporters he came up with the surname by using the first three letters of his first name, "NOR", followed by the letter "L" for Levinson and another "L" for appearance. Norman never legally changed his surname to Norell. Following completion of his coursework at Pratt, Norell began his fashion career as a costume designer in New York City. In 1922 Norell joined the Paramount Pictures studios based in Astoria, Queens, New York, where he designed clothes for Gloria Swanson, Rudolph Valentino, and other stars of silent-film stars. Norell designed costumes for Zaza (1923) starring Swanson and was one of three costume designers for A Sainted Devil (1924) starring Valentino. Norell lost his job when the film industry relocated to California. He remained in New York and found work as a costume designer for the Broadway theater. Norell made costumes for the Ziegfeld Follies, as well as for the Brooks Costume Company. Beginning in 1924 Norell spent three and a half years with Charles Armour, a wholesale dress manufacturer, learning how to make real clothes for women instead of crafting theatrical costumes. In 1928 Hattie Carnegie, a major name in the U.S. fashion industry at the time, hired Norell as a designer for her custom-order house. After Norell joined the firm Carnegie introduced her first line of high-quality, high-priced, ready-to-wear fashions that he had designed. The Carnegie-Norell duo also created fashions for celebrities and film stars such as Joan Crawford and Constance Bennett. Novell remained with Carnegie for twelve years. They split in 1941 after a disagreement about the gowns he had designed for Gertrude Lawrence, the star of the Broadway musical, Lady in the Dark. When Norell left Carnegie's fashion house in 1941, he was not yet in the financial position to open his own fashion-design business, but he had earned a strong reputation for his designs within the industry. Anthony Traina, a wholesale clothing manufacturer, offered Norell a partnership. Traina would look after the business while Norell designed the fashions. Traina offered Norell a larger salary if Norell's name did not appear on the label, a smaller salary if it did. Norell chose the lower salary/better visibility option. Traina-Norell launched its first collection in 1941. Norell’s fashions for the Traina-Norell label became famous for their detailing, simplicity, timeless design, and high-quality construction. According to The New York Times, the Traina-Norell collection became a "status symbol among American women." Norell's designs for a chemise, a sequin-covered sheath dress, and a fur-trimmed trench coat helped make the Traina-Norell label "a fashion byword," whose prestige equaled the Parisian labels. During the World War II-era Norman Norell became the leading New York fashion designer. He was the first among the New York designers to introduce a full collection of fashions, rather than an assortment of separate pieces. Norell's wool jersey dresses became staples of the Traina-Norell label, as did his sailor-suit-inspired dresses and spangle-covered "mermaid" gowns (a skin-tight, floor-length evening gown). In 1943, Norell became the first recipient of the American Fashion Critics' Award, later known as the Coty Fashion Award. That same year he accepted a teaching position in the fashion design department at New York's Parsons School of Design. Norell contributed to the war effort as a volunteer on the weekends in New York's hospitals to help care for wounded soldiers. Although Norell made annual trips to Paris after World War II to purchase fabric and traveled across the United States to show and sell his work, he remained a New York City resident for the rest of his life. Norell turned down an offer from Harry Cohn, head of Columbia Pictures, to move to Hollywood and create costume designs for the film studio. During the 1950s Norell's biannual shows of his collection at his firm's New York City showroom at 550 Seventh Avenue were lavish, black tie events. Norell received his second Coty Award in 1951 and became the first winner of the fashion industry critics' Hall of Fame award in 1956, the same year Norell designed Marilyn Monroe's wedding dress for her marriage to playwright Arthur Miller. After Traina retired in 1960 Norell and several silent partners established the Norell fashion house. Norell retained ownership of fifty-one percent of the company's stock. The firm's main office and showroom were on Seventh Avenue; its factory in lower Manhattan employed 150 workers. Norell held his first solo fashion show in June 1960. In the early 1960s Norell had become "the label of choice for the fashionable and the famous." Norell amassed numerous private clients, including Hollywood stars such as Marilyn Monroe, Lauren Bacall, Judy Garland, Carol Channing, Dinah Shore, and Lena Horne. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Lady Bird Johnson, Babe Paley, and Lyn Revson, the wife of Revlon cosmetics founder Charles Revson, were also among his private clients. On occasion, Norell created designs for Hollywood films, including three ensembles for Doris Day that appeared in That Touch of Mink (1962) and fashions for the film Sex and the Single Girl (1964). In 1968 Norell became the first American fashion designer to launch his own brand of perfume, marketed by Revlon. Norell took an active role in making selections for the composition of the new fragrance, which he described as "floral with green overtones." The perfume sold at $50 an ounce when it was successfully introduced in 1968, earning Norell an estimated $1 million. The venture provided him with sufficient funds to buy out his silent partners and become the sole owner of the Norell fashion house. Norell's dominance of the American fashion industry began to decline in the late 1960s as other designers, such as Bill Blass and Halston, rose to prominence, but Norell was widely considered "the dean of the fashion industry" in the United States. Known throughout his career for his calm demeanor and easy-going manner, Norell lived a quiet, private life in New York City. He also maintained a lifelong relationship with his Indiana family, returning to Indiana for Christmas holidays and annual summer vacations for many years. Norell, a chain smoker, was diagnosed with throat cancer and underwent successful surgery on his vocal cords in 1962. His voice remained a hoarse whisper for the remainder of his life. Norell underwent a hernia operation in 1969. Newspapers also reported that he suffered from migraine headaches and diverticulitis. Throughout his life, Norell maintained a close relationship with Parsons School of Design . Over the years Norell became known for making impromptu visits to the school to assist Parsons students with their projects. For more than twenty years he served as a critic in Parsons' fashion department, where he was once been a student. Norell also mentored younger designers such as Bill Blass, another fashion designer from Indiana, and Stephen Sprouse. A retrospective show presented by the Parsons School of Design to honor Norell's fifty years in the fashion industry was scheduled to open at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on October 16, 1972. But Norell suffered a stroke on October 15, 1972, he was rushed to New York City's Lenox Hill Hospital. Norell never regained consciousness and died on October 25, 1972, at the age of seventy-two. The retrospective show went on as planned. Norman Norell's funeral service was held at the Unitarian Church of All Souls in Manhattan. Norell's remains are interred at Crownland Cemetery, Noblesville, Indiana, along with other members of the Levinson family. Norell's career in the fashion industry spanned five decades, beginning in 1922, when he worked as a costume designer for Paramount Pictures in Astoria, Queens, until his death in 1972, when he was the sole owner of his own fashion house on New York City's Seventh Avenue. Over the years Norell's clients included Hollywood film stars and entertainers, as well as socialites and the wives of politicians and industrialists. Called the "dean of American fashion designers," Norell was the first recipient of the first fashion industry critics’ Coty Award. From the early 1940s through the 1960s his designs helped make the New York's fashion houses with which he was associated rivals to Parisian firms. The New York Times noted that Norell's designs were known for their "glamour, timelessness and high quality construction." Fashion critics also praised Norell for his keen eye for detail, accuracy in judging proper proportion, effective use of color, and insistence on high-quality workmanship. Norell's lavish, avant-garde fashion shows showcased his designs that were tailored for the American woman's active lifestyle. He was well known for his high quality, tailored fashions. He was especially known for his sailor-inspired clothes, chemise dresses, wool jersey dresses, and Empire-line dresses, as well as culottes and sequin-covered, "mermaid" evening gowns and sheath dresses. In the late 1960s, during the height of his popularity, Norell's "mermaid" gowns sold for $3,000 to $4,000, "considered the most expensive dresses in America" at that time. To make sure that imitations of his design for culottes would be constructed correctly, Norell published the specifications in Women's Wear Daily. Norell believed that his greatest contribution to fashion was the inclusion of simple, no-neckline dresses. Beginning in 2000 the City of New York placed bronze plaques honoring American designers along Seventh Avenue and Norell was among the first to be honored. Further interestBooks  Norell: Master of American FashionAuthor Jeffrey Banks and Doria de la Chapelle, Foreword by Ralph Rucci, Afterword by Kenneth PoolThe first book dedicated to the career and creations of esteemed fashion designer Norman Norell, the man hailed as the “Dean of American Fashion” by the New York Times. Norman Norell (1900–1972)—the first American designer to employ couture techniques, refined workmanship, and luxurious fabrics—made dresses, coats, and suits that critics deemed “the equal of Paris,” earning him the sobriquet “the American Balenciaga” and forever changing perceptions about New York’s Seventh Avenue garment industry. Norell showed the world that American design could climb to great heights by producing collection after collection that was both elegant and practical. He singlehandedly shaped the character of the ready-to-wear industry and served as a role model to younger generations of American designers. Early jobs included creating costumes for film and stage and outfits for the stars themselves, as well as working for fashion entrepreneur Hattie Carnegie. Norell brought to the world a lean sophistication and American glamour in his daytime suits, jersey separates, swing coats, and his shimmering sequined “mermaid” dresses. Clients included Lauren Bacall, Babe Paley, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Lena Horne, Dinah Shore, Marilyn Monroe, and Lady Bird Johnson. Norell was the first thoroughly modern American designer—and his dresses are still prized by stylish women today. About The AuthorJeffrey Banks is a Coty Award–winning designer of men’s and women’s apparel. Doria de La Chapelle is a freelance writer. She has written on fashion, beauty, and style for Mademoiselle magazine and other publications. Ralph Rucci is a fashion designer and artist. Stan Herman is a clothing designer and former CFDA president. Kenneth Pool is a bridal-dress designer and Norell collector.

0 Comments

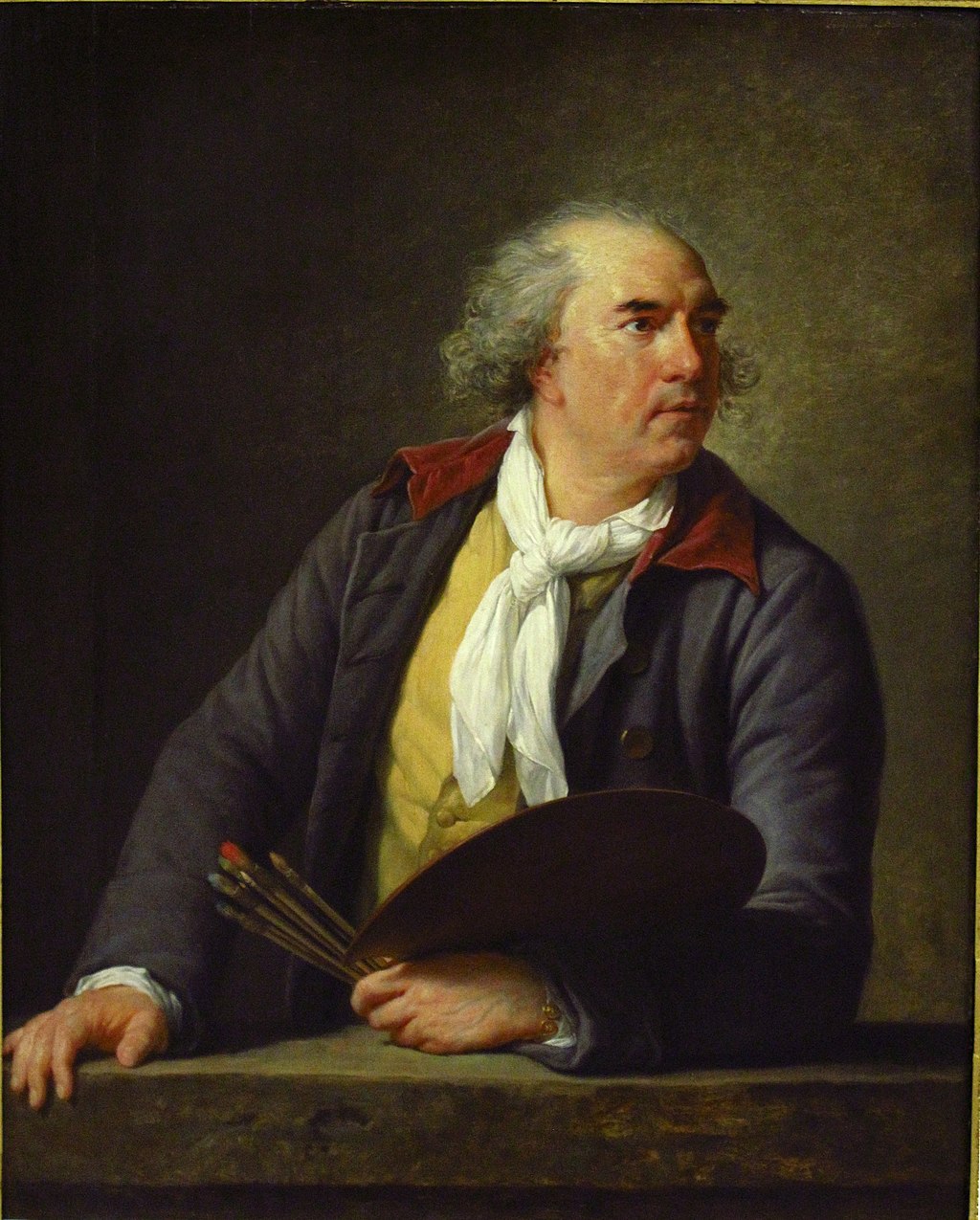

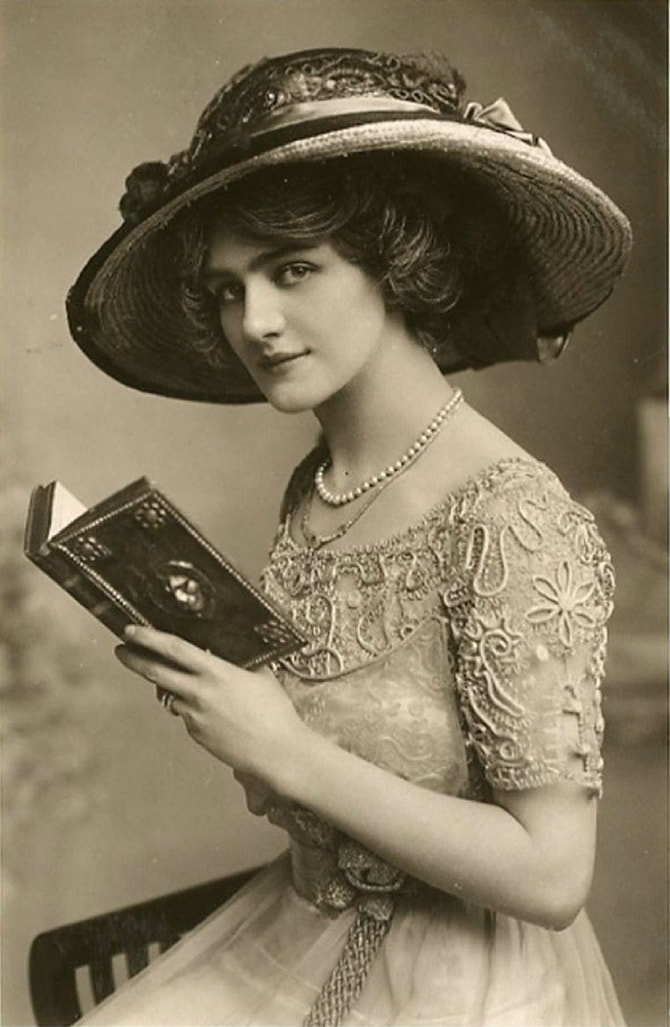

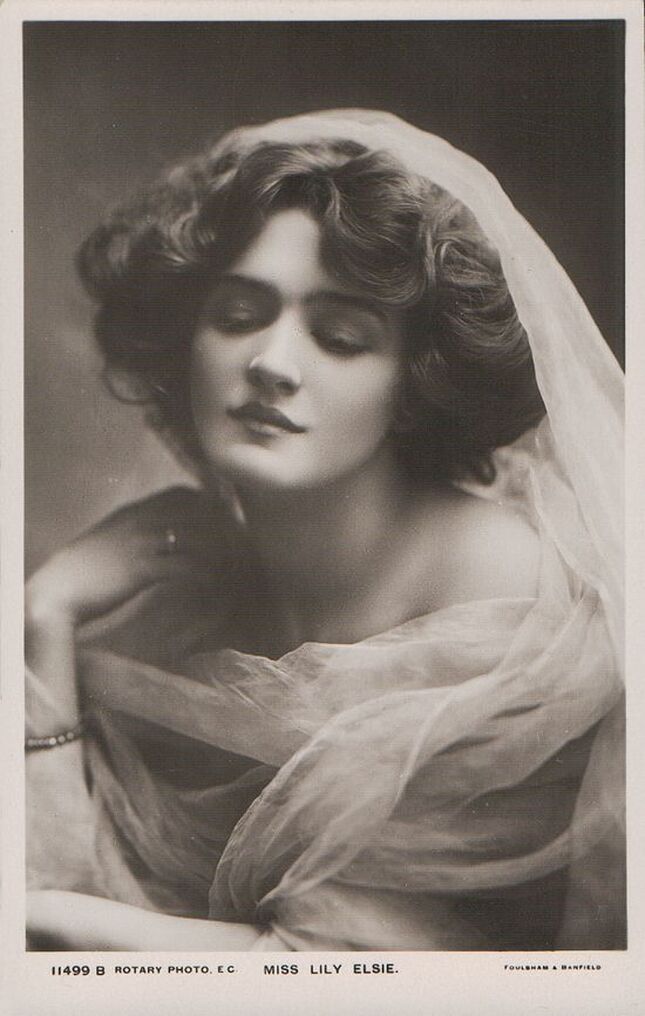

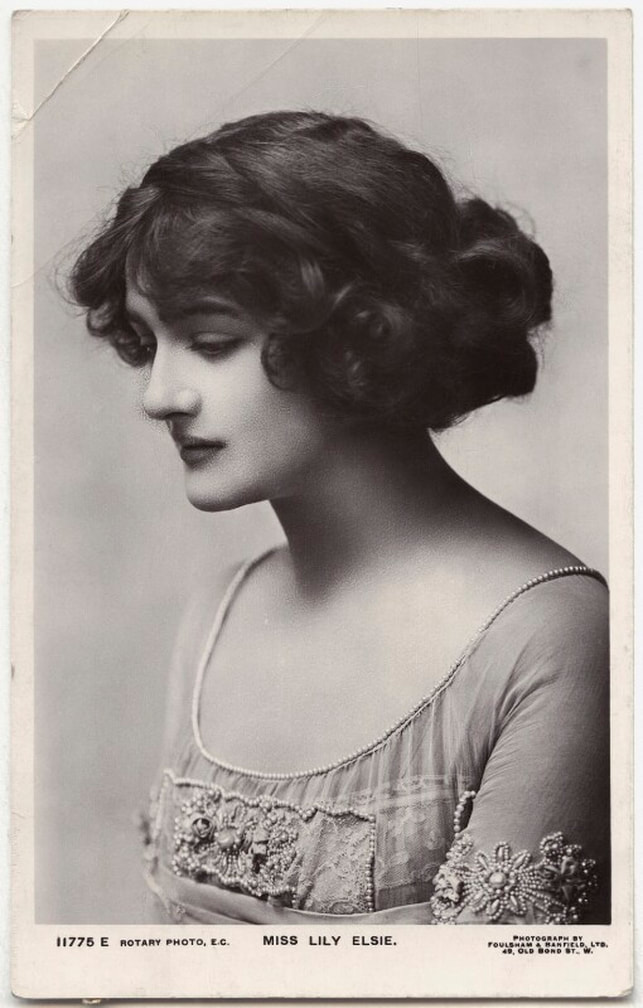

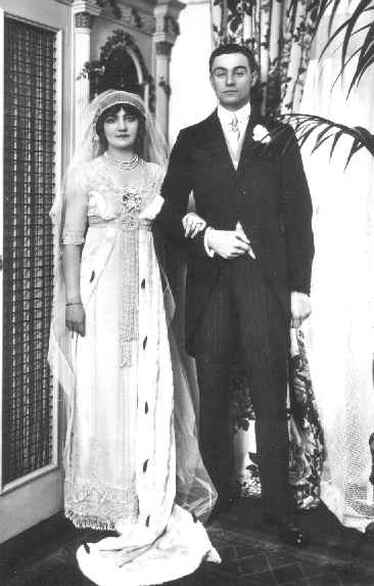

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (16 April 1755 – 30 March 1842), also known as Madame Le Brun, was a French portrait painter in the late 18th century. Her artistic style is generally considered part of the aftermath of Rococo with elements of an adopted Neoclassical style. Her subject matter and color palette can be classified as Rococo, but her style is aligned with the emergence of Neoclassicism. Vigée Le Brun created a name for herself in Ancien Régime society by serving as the portrait painter to Marie Antoinette. She enjoyed the patronage of European aristocrats, actors, and writers, and was elected to art academies in ten cities. Vigée Le Brun created 660 portraits and 200 landscapes. In addition to many works in private collections, her paintings are owned by major museums, such as the Louvre Paris, Uffizi Florence, Hermitage Museum Saint Petersburg, National Gallery in London, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and many other collections in continental Europe and the United States. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, aussi appelée Élisabeth Vigée, Élisabeth Le Brun ou Élisabeth Lebrun, née Louise-Élisabeth Vigée le 16 avril 1755 à Paris, et morte dans la même ville le 30 mars 1842, est une artiste peintre française, considérée comme une grande portraitiste de son temps. Elle a été comparée à Quentin de La Tour ou Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Son art et sa carrière exceptionnelle en font un témoin privilégié des bouleversements de la fin du xviiie siècle, de la Révolution Française et de la Restauration. Fervente royaliste, elle sera successivement peintre de la cour de France, de Marie-Antoinette et de Louis XVI, du Royaume de Naples, de la Cour de l'empereur de Vienne, de l'empereur de Russie et de la Restauration. On lui connaît aussi plusieurs autoportraits, dont deux avec sa fille. BiographyBorn in Paris on 16 April 1755, Élisabeth Louise Vigée was the daughter of Jeanne (1728–1800), a hairdresser from a peasant background, and Louis Vigée, a portraitist, pastellist and member of the Académie de Saint-Luc, from whom she received her first instruction. In 1760, at the age of five, she entered a convent, where she remained until 1766. Her father died when she was 12 years old. In 1768, her mother married a wealthy jeweller, Jacques-François Le Sèvre, and shortly after, the family moved to the Rue Saint-Honoré, close to the Palais Royal. In her memoir, Vigée Le Brun directly stated her feelings about her step-father: "I hated this man; even more so since he made use of my father's personal possessions. He wore his clothes, just as they were, without altering them to fit his figure.” During this period, Élisabeth benefited from the advice of Gabriel François Doyen, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and Joseph Vernet, whose influence is evident in her portrait of her younger brother, playwright and poet Étienne Vigée. By the time she was in her early teens, Élisabeth was painting portraits professionally. After her studio was seized for her practicing without a license, she applied to the Académie de Saint-Luc, which unwittingly exhibited her works in their Salon. In 1774, she was made a member of the Académie. On 11 January 1776, she married Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, a painter and art dealer. Her husband's great-great-uncle was Charles Le Brun, the first director of the French Academy under Louis XIV. Vigée Le Brun began exhibiting her work at their home in Paris, the Hôtel de Lubert, and the Salons she held here supplied her with many new and important contacts. On 12 February 1780, Vigée Le Brun gave birth to a daughter, Jeanne Lucie Louise, whom she called Julie and nicknamed "Brunette". In 1781 she and her husband toured Flanders and the Netherlands, where seeing the works of the Flemish masters inspired her to try new techniques. Her Self-portrait with Straw Hat (1782) was a "free imitation" of Peter Paul Rubens' Le Chapeau de Paille. Dutch and Flemish influences have also been noted in her later paintings The Comte d'Espagnac (1786) and Madame Perregaux (1789). As her career blossomed, Vigée Le Brun was granted patronage by Marie Antoinette. She painted more than 30 portraits of the queen and her family, leading to the common perception that she was the official portraitist of Marie Antoinette. At the Salon of 1783, Vigée Le Brun exhibited Marie-Antoinette in a Muslin Dress (1783), sometimes called Marie-Antoinette en gaulle, in which the queen chose to be shown in a simple, informal white cotton garment. The resulting scandal was prompted by both the informality of the attire and the queen's decision to be shown in that way. On 31 May 1783, Vigée Le Brun was received as a member of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. She was one of only 15 women to be granted full membership in the Académie between 1648 and 1793. Her rival, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, was admitted on the same day. Vigée Le Brun was initially refused on the grounds that her husband was an art dealer, but eventually the Académie was overruled by an order from Louis XVI because Marie Antoinette put considerable pressure on her husband on behalf of her portraitist. As her reception piece, Vigée Le Brun submitted an allegorical painting, Peace Bringing Back Abundance (La Paix ramenant l'Abondance), instead of a portrait. As a consequence, the Académie did not place her work within a standard category of painting—either history or portraiture. Vigée Le Brun's membership in the Académie dissolved after the French Revolution because female academicians were abolished. Vigée Le Brun's later Marie Antoinette and Her Children (1786) was evidently an attempt to improve the queen's image by making her more relatable to the public, in the hopes of countering the bad press and negative judgments that the queen had recently received. The portrait shows the queen at home in the Palace of Versailles, engaged in her official function as the mother of the king's children, but also suggests Marie Antoinette's uneasy identity as a foreign-born queen whose maternal role was her only true function under Salic law. The child, Louis Joseph, on the right is pointing to an empty cradle, which signified her recent loss of a child, further emphasizing Marie Antoinette's role as a mother. In 1787, she caused a minor public scandal when her Self-portrait with Her Daughter Julie (1786) was exhibited at the Salon of 1787 showing her smiling and open-mouthed, which was in direct contravention of traditional painting conventions going back to antiquity. The court gossip-sheet Mémoires secrets commented: "An affectation which artists, art-lovers and persons of taste have been united in condemning, and which finds no precedent among the Ancients, is that in smiling, [Madame Vigée LeBrun] shows her teeth." In light of this and her other Self-portrait with Her Daughter Julie (1789), Simone de Beauvoir dismissed Vigée Le Brun as narcissistic in The Second Sex (1949): "Madame Vigée-Lebrun never wearied of putting her smiling maternity on her canvases.” In October 1789, after the arrest of the royal family during the French Revolution, Vigée Le Brun fled France with her young daughter, Julie. Her husband, who remained in Paris, claimed that Vigée Le Brun went to Italy "to instruct and improve herself", but she certainly feared for her own safety. In her 12-year absence from France, she lived and worked in Italy (1789–1792), Austria (1792–1795), Russia (1795–1801) and Germany (1801). While in Italy, Vigée Le Brun was elected to the Academy in Parma (1789) and the Accademia di San Luca in Rome (1790). In Naples, she painted portraits of Maria Carolina of Austria (sister of Marie Antoinette) and her eldest four living children: Maria Teresa, Francesco, Luisa and Maria Cristina. She later recalled that Luisa "was extremely ugly, and pulled such faces that I was most reluctant to finish her portrait." Vigée Le Brun also painted allegorical portraits of the notorious Emma Hamilton as Ariadne (1790) and as a Bacchante (1792). Lady Hamilton was similarly the model for Vigée Le Brun's Sibyl (1792), which was inspired by the painted sibyls of Domenichino.The painting represents the Cumaean Sibyl, as indicated by the Greek inscription on the figure's scroll, which is taken from Virgil's fourth Eclogue. The Sibyl was Vigée Le Brun's favorite painting. It is mentioned in her memoir more than any other work. She displayed it while in Venice (1792), Vienna (1792), Dresden (1794) and Saint Petersburg (1795); she also sent it to be shown at the Salon of 1798. Like her reception piece, Peace Bringing Back Abundance, Vigée Le Brun regarded her Sibyl as a history painting, the most elevated category in the Académie's hierarchy. While in Vienna, Vigée Le Brun was commissioned to paint Princess Maria Josefa Hermengilde von Esterhazy as Ariadne, and its pendant Princess Karoline von Liechtenstein as Iris Princess Karoline. The portraits depict the Liechtenstein sisters-in-law in unornamented Roman-inspired garments that show the influence of Neoclassicism, and which may have been a reference to the virtuous republican Roman matron Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi. In Russia, where she stayed from 1795 until 1801, she was well-received by the nobility and painted numerous aristocrats, including the former king of Poland, Stanisław August Poniatowski, and members of the family of Catherine the Great. Although the French aesthetic was widely admired in Russia, there remained various cultural differences as to what was deemed acceptable. Catherine was not initially happy with Vigée Le Brun's portrait of her granddaughters, Elena and Alexandra Pavlovna, due to the amount of bare skin the short-sleeved gowns revealed. In order to please the Empress, Vigée Le Brun added sleeves. This tactic seemed effective in pleasing Catherine, as she agreed to sit herself for Vigée Le Brun (although Catherine died of a stroke before this work was due to begin). While in Russia, Vigée Le Brun was made a member of the Academy of Fine Arts of Saint Petersburg. Much to Vigée Le Brun's dismay, her daughter Julie married Gaétan Bernard Nigris, secretary to the Director of the Imperial Theaters of Saint Petersburg. Julie predeceased her mother in 1819. After a sustained campaign by her ex-husband and other family members to have her name removed from the list of counter-revolutionary émigrés, Vigée Le Brun was finally able to return to France in January 1802. She travelled to London in 1803, to Switzerland in 1807, and to Switzerland again in 1808. In Geneva, she was made an honorary member of the Société pour l'Avancement des Beaux-Arts. She stayed at Coppet with Madame de Staël, who appears as the title character in Corinne, ou l'Italie (1807). In her later years, Vigée Le Brun purchased a house in Louveciennes, Île-de-France and divided her time between Louveciennes and Paris. She died in Paris on 30 March 1842, aged 86. She was buried at the Cimetière de Louveciennes near her old home. Her tombstone epitaph says "Ici, enfin, je repose..." (Here, at last, I rest...). Between 1835 and 1837, when Vigée Le Brun was in her 80s, she published her memoirs in three volumes (Souvenirs). During her lifetime, Vigée Le Brun's work was publicly exhibited in Paris at the Académie de Saint-Luc (1774), Salon de la Correspondance (1779, 1781, 1782, 1783) and Salon of the Académie in Paris (1783, 1785, 1787, 1789, 1791, 1798, 1802, 1817, 1824). The first retrospective exhibition of Vigée Le Brun's work was held in 1982 at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. The first major international retrospective exhibition of her art premiered at the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais in Paris (2015—2016) and was subsequently shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (2016) and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa (2016). BiographieÉlisabeth-Louise voit le jour en 1755. Ses parents, Louis Vigée, pastelliste et membre de l’Académie de Saint-Luc et Jeanne Maissin, d’origine paysanne, se marient en 1750; un frère cadet, Étienne Vigée, qui deviendra un auteur dramatique à succès, naît deux ans plus tard. Née rue Coquillière à Paris, Élisabeth est baptisée à l’église Saint-Eustache de Paris, puis mise en nourrice. Dans la bourgeoisie et l'aristocratie, il n'est pas encore dans les habitudes d'élever ses enfants soi-même, aussi l’enfant est-elle confiée à des paysans des environs d’Épernon. Son père vient la rechercher six ans plus tard, la ramène à Paris dans l'appartement familial rue de Cléry. Élisabeth-Louise entre comme pensionnaire à l’école du couvent de la Trinité, rue de Charonne dans le faubourg Saint-Antoine, afin de recevoir la meilleure éducation possible. Dès cet âge, son talent précoce pour le dessin s’exprime : dans ses cahiers, sur les murs de son école. En 1766, Élisabeth-Louise quitte le couvent et vient vivre aux côtés de ses parents. Son père meurt accidentellement d'une septicémie après avoir avalé une arête de poisson, le 9 mai 1767. Élisabeth-Louise, qui n'a que douze ans, mettra longtemps à faire son deuil puis décide de s'adonner à ses passions, la peinture, le dessin et le pastel. Sa mère se remarie dès le 26 décembre 1767 avec un joaillier fortuné mais avare, Jacques-François Le Sèvre (1724-1810) ; les relations d'Élisabeth-Louise avec son beau-père sont difficiles. Le premier professeur d’Élisabeth fut son père, Louis Vigée. Après le décès de ce dernier, c’est un autre peintre, Gabriel-François Doyen, meilleur ami de la famille et célèbre en son temps comme peintre d'histoire, qui l’encourage à persévérer dans le pastel et dans l’huile ; conseil qu’elle suivra. C’est certainement conseillée par Doyen, qu’en 1769 Élisabeth Vigée se rend chez le peintre Gabriel Briard, une connaissance de ce dernier (pour avoir eu le même maître, Carl van Loo). Briard est membre de l’Académie royale de peinture, et donne volontiers des leçons, bien qu'il ne soit pas encore professeur. Peintre médiocre, il a surtout la réputation d’être un bon dessinateur et possède en plus un atelier au palais du Louvre ; Élisabeth fait de rapides progrès et, déjà, commence à faire parler d’elle. C’est au Louvre qu’elle fait la connaissance de Joseph Vernet, artiste célèbre dans toute l’Europe. Il est l'un des peintres les plus courus de Paris, ses conseils font autorité, et il ne manquera pas de lui en prodiguer. « J’ai constamment suivi ses avis ; car je n’ai jamais eu de maître proprement dit », écrit-elle dans ses mémoires. Quoi qu’il en soit, Vernet, qui consacrera de son temps à la formation de « Mlle Vigée », et Jean-Baptiste Greuze la remarquent et la conseillent. Elle peint son premier tableau reconnu en 1770, un portrait de sa mère (Madame Le Sèvre). En 1770, le dauphin Louis-Auguste, futur Louis XVI, petit-fils du roi Louis XV, épouse Marie-Antoinette d'Autriche à Versailles, fille de l'impératrice Marie-Thérèse. À la même époque, la famille Le Sèvre-Vigée s’installe rue Saint-Honoré, face au Palais-Royal, dans l'hôtel de Lubert. Louise-Élisabeth Vigée commence à réaliser des portraits de commande et à peindre de nombreux autoportraits. Lorsque son beau-père se retire des affaires en 1775, la famille s'installe rue de Cléry, dans l'hôtel Lubert, dont le principal locataire est Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Lebrun qui exerce les professions de marchand et restaurateur de tableaux, d'antiquaire et de peintre. Il est un spécialiste de peinture hollandaise dont il a publié des catalogues. Elle visite avec le plus vif intérêt la galerie de tableaux de Lebrun et y parfait ses connaissances picturales. Ce dernier devient son agent, s'occupe de ses affaires. Déjà marié une première fois en Hollande, il la demande en mariage. Libertin et joueur, il a mauvaise réputation, et le mariage est formellement déconseillé à la jeune artiste. Cependant, désireuse d'échapper à sa famille, elle l'épouse le 11 janvier 1776 dans l'intimité. Élisabeth Vigée devient Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. Elle reçoit cette même année sa première commande de la Cour du comte de Provence, le frère du roi puis, le 30 novembre 1776, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun est admise à travailler pour la Cour de Louis XVI. En 1778, elle devient peintre officielle de la reine et est donc appelée pour réaliser le premier portrait de la reine Marie-Antoinette d'après nature. Son hôtel particulier devient un lieu à la mode, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun traverse une période de succès et son mari y ouvre une salle des ventes dans laquelle il vend des antiquités et des tableaux de Greuze, Fragonard, etc. Elle vend ses portraits pour 12 000 francs sur lesquels elle ne touche que 6 francs, son mari empochant le reste, comme elle le dit dans ses Souvenirs : « J'avais sur l'argent une telle insouciance, que je n'en connaissais presque pas la valeur. » Le 12 février 1780, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun donne naissance à sa fille Jeanne-Julie-Louise. Elle continue à peindre pendant les premières contractions et, dit-on, lâche à peine ses pinceaux pendant l’accouchement. Sa fille Julie sera le sujet de nombreux portraits. Une seconde grossesse quelques années plus tard donnera un enfant mort en bas âge. En 1781, elle voyage à Bruxelles avec son mari pour assister et acheter à la vente de la collection du défunt gouverneur Charles-Alexandre de Lorraine ; elle y rencontre le prince de Ligne. Inspirée par Rubens qu'elle admire, elle peint son Autoportrait au chapeau de paille en 1782 (Londres, National Gallery). Alors qu'elle n'arrivait pas à y être admise, elle est reçue à l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture le 31 mai 1783 en même temps que sa concurrente Adélaïde Labille-Guiard et contre la volonté de Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre, premier peintre du roi. Son sexe et la profession de son mari marchand de tableaux sont pourtant de fortes oppositions à son entrée, mais l'intervention protectrice de Marie-Antoinette lui permet d'obtenir ce privilège de Louis XVI. Vigée Le Brun présente une peinture de réception (alors qu’on ne lui en demandait pas), La Paix ramenant l’Abondance réalisée en 1783 (Paris, musée du Louvre), pour être admise en qualité de peintre d’Histoire. Forte de l'appui de la reine, elle se permet l'impertinence d'y montrer un sein découvert, alors que les nus académiques étaient réservés aux hommes. Elle est reçue sans qu’aucune catégorie soit précisée. En septembre de la même année, elle participe au Salon pour la première fois et y présente Marie-Antoinette dit « à la Rose » : initialement, elle a l'audace de présenter la reine dans une robe en gaule, mousseline de coton qui est généralement utilisée en linge de corps ou d'intérieur, mais les critiques se scandalisent du fait que la reine s'est fait peindre en chemise, si bien qu'au bout de quelques jours, Vigée Le Brun doit le retirer et le remplacer par un portrait identique mais avec une robe plus conventionnelle. Dès lors, les prix de ses tableaux s'envolent. Avant 1789, l'œuvre d'Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun est composé de portraits, genre à la mode dans la seconde moitié du xviiie siècle, pour les clients fortunés et aristocratiques qui constituent sa clientèle. Parmi ses portraits de femmes, on peut citer notamment les portraits de Marie-Antoinette (une vingtaine sans compter ceux des enfants) ; Catherine Noël Worlee (la future princesse de Talleyrand) qu’elle réalisa en 1783 et qui fut exposé au Salon de peinture de Paris de cette même année 1783 ; la sœur de Louis XVI, Mme Élisabeth ; l'épouse du comte d'Artois ; deux amies de la reine : la princesse de Lamballe et la comtesse de Polignac. En 1786, elle peint son premier autoportrait avec sa fille et le portrait de Marie-Antoinette et ses enfants. Les deux tableaux sont exposés au Salon de peinture de Paris de la même année et c'est l'autoportrait avec sa fille qui est encensé par le public. En 1788, elle peint ce qu'elle considère comme son chef-d'œuvre : Le Portrait du peintre Hubert Robert. Au sommet de sa gloire, dans son hôtel particulier parisien, rue de Cléry, où elle reçoit une fois par semaine la haute société, elle donne un « souper grec », qui défraye la chronique par l'ostentation qui s'y déploie et pour laquelle on la soupçonne d'avoir dépensé une fortune. Le coût du dîner de 20 000 francs fut rapporté au roi Louis XVI qui s'emporta contre l'artiste. À l’été 1789, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun se trouve à Louveciennes chez la comtesse du Barry, la dernière maîtresse de Louis XV, dont elle a commencé le portrait, lorsque les deux femmes entendent le canon tonner dans Paris. Dans la nuit du 5 au 6 octobre 1789, alors que la famille royale est ramenée de force à Paris, Élisabeth quitte la capitale avec sa fille, Julie, sa gouvernante et cent louis, laissant derrière elle son époux qui l'encourage à fuir, ses peintures et le million de francs qu'elle a gagné à son mari, n'emportant que 20 francs, écrit-elle dans ses Souvenirs. Elle arrive à Rome en novembre 1789. En 1790, elle est reçue à la Galerie des Offices en réalisant son Autoportrait, qui obtient un grand succès. Elle envoie des œuvres à Paris au Salon. L’artiste effectue son Grand Tour et vit entre Florence, Rome où elle retrouve Ménageot, et Naples avec Talleyrand et Lady Hamilton, puis Vivant Denon, le premier directeur du Louvre, à Venise. Elle veut rentrer en France, mais elle est inscrite, en 1792, sur la liste des émigrés et perd ainsi ses droits civiques. Elle se rend à Vienne en Autriche, d'où elle ne pense pas partir et où, en tant qu'ancienne peintre de la reine Marie-Antoinette, elle bénéficie de la protection de la famille impériale. À Paris, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Lebrun a vendu tout son fonds de commerce en 1791 pour éviter la faillite, alors que le marché de l'art s'est effondré et a perdu la moitié de sa valeur. Proche de Jacques-Louis David, il demande en 1793, sans succès, que le nom de sa femme soit retiré de la liste des émigrés. Invoquant la désertion de sa femme, Jean-Baptiste-Pierre demande et obtient le divorce en 1794 pour se protéger et préserver leurs biens. Quant à Elisabeth-Louise, elle parcourt l'Europe en triomphe. En 1809, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun revient en France et s'installe à Louveciennes, dans une maison de campagne voisine du château ayant appartenu à la comtesse du Barry (guillotinée en 1793) dont elle avait peint trois portraits avant la Révolution. Elle vit alors entre Louveciennes et Paris. À Louveciennes, où elle vit huit mois de l'année, le reste en hiver à Paris, où elle tient salon et croise les artistes en renom le dimanche. Son mari, dont elle avait divorcé, meurt en 1813. En 1814, elle se réjouit du retour de Louis XVIII, « Le monarque qui convenait à l'époque », écrit-elle dans ses mémoires. Après 1815 et la Restauration, ses tableaux, en particulier les portraits de Marie-Antoinette, sont restaurés et ré-accrochés au Louvre, à Fontainebleau et à Versailles. Sa fille finit sa vie dans la misère en 1819, et son frère, Étienne Vigée, meurt en 1820. Elle effectue un dernier voyage à Bordeaux au cours duquel elle effectue de nombreux dessins de ruines. En 1835, elle publie ses Souvenirs avec l'aide de ses nièces Caroline Rivière, venue vivre avec elle, et d'Eugénie Tripier Le Franc, peintre portraitiste et dernière élève. C'est cette dernière qui écrit de sa main une partie des souvenirs du peintre, d'où les doutes émis par certains historiens quant à leur authenticité. À la fin de sa vie, l'artiste en proie à des attaques cérébrales, perd la vue. Elle meurt à Paris à son domicile de la rue Saint-Lazare le 30 mars 1842 et est enterrée au cimetière paroissial de Louveciennes. Sur la pierre tombale, privée de sa grille d'entourage, se dresse la stèle de marbre blanc portant l'épitaphe « Ici, enfin, je repose… », ornée d'un médaillon représentant une palette sur un socle et surmontée d'une croix. Sa tombe a été transférée en 1880 au cimetière des Arches de Louveciennes, lorsque l'ancien cimetière a été désaffecté. À l'invitation de l'ambassadeur de Russie, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun se rend en Russie, pays qu'elle considèrera comme sa seconde patrie. En 1799, une pétition de deux cent cinquante-cinq artistes, littérateurs et scientifiques demandent au Directoire le retrait de son nom de la liste des émigrés. En 1800, son retour est précipité par le décès de sa mère à Neuilly et le mariage, qu'elle n'approuve pas, de sa fille Julie avec Gaëtan Bertrand Nigris, directeur des Théâtres impériaux à Saint-Pétersbourg. C'est pour elle un déchirement. Déçue par son mari, elle avait fondé tout son univers affectif sur sa fille. Les deux femmes ne se réconcilieront jamais totalement. Elle est accueillie à Paris le 18 janvier 1802, où elle retrouve son mari, avec qui elle revit sous le même toit. Si le retour d’Élisabeth est salué par la presse, elle a du mal à retrouver sa place dans la nouvelle société née de la Révolution et de l'Empire. Quelques mois plus tard, elle quitte la France pour l'Angleterre, où elle s'installe à Londres pour trois ans. Là, elle rencontre Lord Byron, le peintre Benjamin West, retrouve Lady Hamilton, la maîtresse de l'amiral Nelson qu'elle avait connue à Naples, et admire la peinture de Joshua Reynolds. Elle vit avec la Cour de Louis XVIII et du comte d'Artois en exil entre Londres, Bath et Douvres. En 1805, elle reçoit la commande du portrait de Caroline Murat, épouse du général Murat, une des sœurs de Napoléon devenue reine de Naples, et cela se passe mal : « J’ai peint de véritables princesses qui ne m’ont jamais tourmentée et ne m’ont pas fait attendre », dira l'artiste quinquagénaire à cette jeune reine parvenue. Le 14 janvier 1807, elle rachète à son mari endetté son hôtel particulier parisien et sa salle des ventes. Mais en butte au pouvoir impérial, Vigée Le Brun quitte la France pour la Suisse, où elle rencontre Madame de Staël en 1807. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun fut célèbre de son vivant, mais son œuvre associée à l'Ancien Regime, et en particulier à la Reine Marie-Antoinette va être sous-estimée jusqu'au xxie siècle. La première rétrospective de son œuvre en France a lieu de septembre 2015 au 11 janvier 2016 au Grand Palais de Paris. Accompagnée de films, de documentaires, la peintre de Marie-Antoinette apparaît alors dans toute sa complexité. ArticlesVideosÉlisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842) : Une vie, une œuvre (2015 / France Culture) The Remarkable Talent Of Elizabeth Vigée Lebrun | Portraits of Marie Antoinette Pt. 1 | Perspective The Prolonged Exile Of France’s Finest Artist | Portraits of Marie Antoinette Part 2 | Perspective Elsie Cotton (née Hodder, 8 April 1886 – 16 December 1962), known professionally as Lily Elsie, was an English actress and singer during the Edwardian era. She was best known for her starring role in the London premiere of Franz Lehár's operetta The Merry Widow. Beginning as a child star in the 1890s, Elsie built her reputation in several successful Edwardian musical comedies before her great success in The Merry Widow, opening in 1907. Afterwards, she starred in several more successful operettas and musicals, including The Dollar Princess (1909), A Waltz Dream (1911) and The Count of Luxembourg (1911). Admired for her beauty and charm on stage, Elsie became one of the most photographed women of Edwardian times. BiographyElsie Cotton was born in Armley, West Yorkshire. Her mother, Charlotte Elizabeth Hodder (1864–1922), was a dressmaker who operated a lodging-house. She married William Thomas Cotton, a theatre worker, in 1891, and Elsie became Elsie Cotton. The family lived in Manchester. A precocious child star, Elsie appeared in music hall and variety entertainments as a child impersonator known as Little Elsie. Nevertheless, she was reportedly painfully shy, even as an adult. By 1895–96, she appeared in concerts and pantomimes in theatres in Salford. In 1896, she played the role of Princess Mirza in The Arabian Nights at the Queen's Theatre in Manchester. Then, at Christmas 1896–97, at the age of ten, she appeared in the title role of Little Red Riding Hood at the same theatre for six weeks and then on tour for six additional weeks. Her first London appearance was at Christmas 1898 in King Klondike at Sara Lane's Britannia Theatre as Aerielle, the Spirit of the Air. Elsie then toured the provinces, travelling as far as Bristol and Hull for a full year in McKenna's Flirtation, a farce by American E. Selden, in 1900. She then played in Christmas pantomimes, including Dick Whittington (1901), The Forty Thieves (1902), and Blue Beard (1903) and toured in Edwardian musical comedies, including The Silver Slipper by Owen Hall, with music by Leslie Stuart (1901–02), and Three Little Maids (1903). From about 1900, she adopted the stage name Lily Elsie. Elsie then joined George Edwardes' company at Daly's Theatre in London as a chorus girl. From 1900 to 1906, she appeared in 14 shows. In 1903, she took over the role of Princess Soo-Soo in the hit musical A Chinese Honeymoon and then starred in the flop, Madame Sherry, by Hugo Felix, at the Apollo Theatre. She next played the roles of Gwenny Holden in Lady Madcap, Lady Patricia Vereker in The Cingalee in 1904, Madame du Tertre in The Little Michus in 1905, and Lady Agnes Congress in The Little Cherub (during which, she was fired by George Edwardes for giggling, but soon rehired), Humming Bird in See See and Lally in The New Aladdin at the Gaiety Theatre, all in 1906. Lily Elsie's biggest success came in creating the title role in the English-language version of The Merry Widow in the London production. George Edwardes took Elsie to see the original German version (Die Lustige Witwe) in Berlin. Elsie was at first reluctant to take on the demanding part, thinking her voice too light for the role, but Edwardes persuaded her to accept. Edwardes brought her to see the famous designer, Lucile, for a style coaching. Lucile later wrote, "I realised that here was a girl who had both beauty and intelligence but who had never learnt how to make the best of herself. So shy and diffident was she in those days that a less astute producer than George Edwardes would in all probability have passed her over and left her in the chorus." The production, with English lyrics by Adrian Ross, opened in June 1907 and ran for 778 performances at Daly's Theatre. Elsie created the role at Daly's and toured with it beginning in August 1908. The show was an enormous success for its creators and made Elsie a major star. One critic at the opening night praised "the youthfulness, the dainty charm and grace, the prettiness and the exquisite dancing with which Miss Elsie invests the part.... I share the opinion of most of the first-nighters, who considered it could not have been in better hands, and could not have been better handled.... The night was a genuine triumph for Miss Elsie, and she well deserved all the calls she received." Lucile designed the costumes for Elsie in The Merry Widow (including the plumed hats that became an extraordinary fad) and thereafter used Elsie to promote her fashions, designing her personal clothes and costumes for several of her other shows. Lucile wrote, "That season was a very brilliant one, perhaps the most brilliant of the series which brought the social life of pre-war London to its peak. And just when it was at its zenith a new play was launched with a new actress, who set the whole town raving over her beauty...." After The Merry Widow, Elsie appeared in another 16 shows, including in the very successful English-language versions of The Dollar Princess in 1909; as Franzi in the British premiere of A Waltz Dream in 1911; and as Angèle in The Count of Luxembourg, also in 1911, garnering continuous praise. One critic wrote that "it gave great pleasure merely to see her walk across the stage." Elsie left the cast of The Count of Luxembourg to marry Major John Ian Bullough (1885–1936), the son of a wealthy textile manufacturer, but the marriage was reported to be mostly unhappy. In addition, Elsie often suffered from ill health, including anaemia, among other ailments, and had several operations during her years onstage. The gossip column in The Pelican called her "the occasional actress". Bullough wanted his wife to retire from the stage. The publicly shy and exhausted Elsie was happy to leave the stage for the next several years, except for charity performances to benefit the war effort. Lily Elsie's image was in great demand by advertisers and on postcards, and she received unsolicited gifts of great value from many male admirers (and even bequests). Lucile commented, "She was absolutely indifferent to most [men] for she once told me she disliked the male character and considered that men only behaved tolerably to a woman who treated them coldly". Nevertheless, Elsie became one of the most frequently photographed beauties of the Edwardian era. According to the Atlanta Constitution newspaper in America, writing in 1915: "Perhaps her face is nearer to that of the Venus de Milo in profile than to any other famed beauty. There are no angles to be found about her any place.... If she came to America, she would undoubtedly be called the most beautiful woman in America. Nature never made a more brilliant success in the beauty business than she did with Lily Elsie. It was mostly from the nobility that her suitors came. Everyone agrees that Lily Elsie has the most kissable mouth in all England... she possesses the Cupid's bow outline with the ends curving upward delicately, all ready for smiles.... Strangely enough, the women of the land were among her most devoted admirers." After a few years, Lily Lesie returned in the title role of Louis Parker's comedy play Malvourneen with Herbert Beerbohm Tree at His Majesty's Theatre, as Lady Catherine Lazenby in The Admirable Crichton in 1916 and in the title role in Pamela written by Arthur Wimperis. In 1920, Elsie moved with her husband to the Gloucestershire village of Redmarley D'Abitot. She spent ten years away from the stage during this time, enjoying social events and fox hunting. She returned to performing, first touring and then appearing at the Prince of Wales's Theatre in London in 1927 as Eileen Mayne in The Blue Train, the English language adaptation of Robert Stolz's German musical comedy Mädi. Her last show before retiring was Ivor Novello's successful The Truth Game back at Daly's Theatre in 1928–1929. Finally, in 1930, Elsie's unhappy marriage ended in divorce as her health deteriorated further and she became subject to fits of ill temper.

She spent much time in nursing homes and Swiss sanatoria. She was diagnosed as having serious psychological ailments and underwent brain surgery that reportedly resulted in an improvement in her health. Her last years were spent at St. Andrew's Hospital in London. Elsie died at St. Andrew's Hospital (demolished in 1973), Cricklewood, London, aged 76, and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|