|

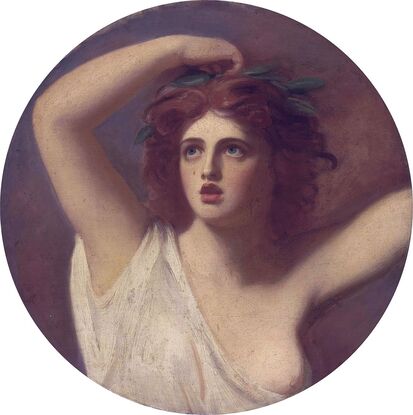

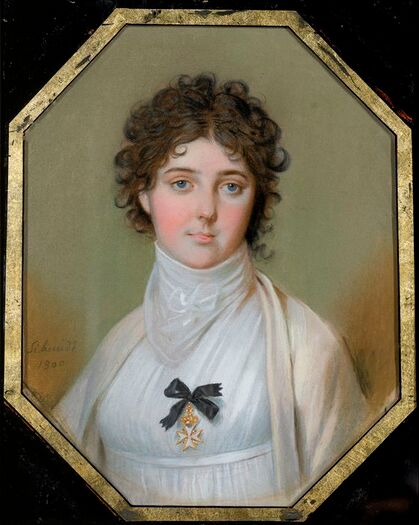

Dame Emma Hamilton (born Amy Lyon; 26 April 1765 – 15 January 1815), generally known as Lady Hamilton, was an English maid, model, dancer and actress. She began her career in London's demi-monde, becoming the mistress of a series of wealthy men, culminating in the naval hero Lord Nelson, and was the favourite model of the portrait artist George Romney. In 1791, at the age of 26, she married Sir William Hamilton, British ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples, where she was a success at court, befriending the queen, the sister of Marie Antoinette, and most famously, having an affair with British war hero, Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson. BiographyEmma was born Amy Lyon in Swan Cottage, Ness near Neston, Cheshire, England, the daughter of Henry Lyon, a blacksmith who died when she was two months old. She was baptised on 12 May 1765. She was raised by her mother, the former Mary Kidd (later Cadogan), and grandmother, Sarah Kidd, at Hawarden, and received no formal education. She later went by the name of Emma Hart. With her grandmother Sarah struggling to make ends meet at the age of 60, and after her mother Mary went to London in 1777, Emma began work, aged 12, as a maid at the Hawarden, home of Doctor Honoratus Leigh Thomas, a surgeon working in Chester. Only a few months later she was unemployed again and moved to London in the autumn of 1777. She started to work for the Budd family in Chatham Place, Blackfriars, London, and began acting at the Drury Lane theatre in Covent Garden. She also worked as a maid for actresses, among them Mary Robinson. Emma next worked as a model and dancer at the "Goddess of Health" for James Graham, a Scottish "quack" doctor. At fifteen, Emma met Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh, who hired her for several months as hostess and entertainer at a lengthy stag party at Fetherstonhaugh's Uppark country estate in the South Downs. She is said to have danced nude on his dining room table. Fetherstonhaugh took Emma there as a mistress, but frequently ignored her in favour of drinking and hunting with his friends. Emma soon befriended the dull but sincere Honourable Charles Francis Greville (1749–1809). It was about this time (late June-early July 1781) that she conceived a child by Fetherstonhaugh. Greville took her in as his mistress, on condition that the child was fostered out. As a young woman, Emma's daughter saw her mother frequently, but later when Emma fell into debt, her daughter worked abroad as a companion or governess. Greville kept Emma in a small house at Edgware Row, Paddington Green, at this time a village on the rural outskirts of London. At Greville's request, she changed her name to "Mrs Emma Hart", dressed in modest outfits in subdued colours and eschewed a social life. He arranged for Emma's mother Mary to live with her as housekeeper and chaperone. Greville also taught Emma to enunciate more elegantly, and after a while, started to invite some of his friends to meet her. Seeing an opportunity to make some money by taking a cut of sales, Greville sent her to sit for his friend, the painter George Romney, who was looking for a new model and muse. It was then that Emma became the subject of many of Romney's most famous portraits, and soon became London's biggest celebrity. So began Romney's lifelong obsession with her, sketching her nude and clothed in many poses that he later used to create paintings in her absence. Through the popularity of Romney's work and particularly of his striking-looking young model, Emma became well known in society circles, under the name of "Emma Hart". She was witty, intelligent, a quick learner, elegant and, as paintings of her attest, extremely beautiful. Romney was fascinated by her looks and ability to adapt to the ideals of the age. Romney and other artists painted her in many guises, foreshadowing her later "attitudes". In 1783, Greville needed to find a rich wife to replenish his finances, and found a fit in the form of eighteen-year-old heiress Henrietta Middleton. Emma would be a problem, as he disliked being known as her lover, and his prospective wife would not accept him as a suitor if he lived openly with Emma Hart. To be rid of Emma, Greville persuaded his uncle, younger brother of his mother, Sir William Hamilton, British Envoy to Naples, to take her off his hands. Sir William had long been happily married until the death of his wife in 1782, and he liked female companionship. Then 55 and newly widowed, he had arrived back in London for the first time in over five years. To promote his plan, Greville suggested to Sir William that Emma would make a very pleasing mistress, assuring him that, once married to Henrietta Middleton, he would come and fetch Emma back. Greville's marriage would be useful to Sir William, as it relieved him of having Greville as a poor relation. Emma's famous beauty was by then well known to Sir William, so much so that he even agreed to pay the expenses for her journey to ensure her speedy arrival. A great collector of antiquities and beautiful objects, he took interest in her as another acquisition. His home in Naples was well known all over the world for hospitality and refinement. He needed a hostess for his salon, and from what he knew about Emma, he thought she would be the perfect choice. Greville did not inform Emma of his plan, but instead in 1785 suggested the trip as a prolonged holiday in Naples, not long after Emma's mother had suffered a stroke. Emma was thus sent to Naples, supposedly for six to eight months, little realising that she was going as the mistress of her host Sir William. Emma set off for Naples with her mother and on 13 March 1786 overland in an old coach, and arrived in Naples on her 21st birthday on 26 April. After about six months of living alone in apartments in the Palazzo Sessa with her mother and begging Greville to come and fetch her, Emma came to understand that he had cast her off. She was furious when she realised what Greville had planned for her, but eventually started to enjoy life in Naples and responded to Sir William's intense courtship just before Christmas in 1786. They fell in love, Sir William forgot about his plan to take her on as a temporary mistress, and Emma moved into his apartments, leaving her mother downstairs in the ground floor rooms. Emma was unable to attend Court yet, but Sir William took her to every other party, assembly and outing. Emma and Sir William were married on 6 September 1791 at St Marylebone Parish Church, London, having returned to England for the purpose and Sir William having gained the King's consent. Emma was twenty-six and Sir William was sixty. Although she was obliged to use her legal name of Amy Lyon on the marriage register, the wedding gave her the title Lady Hamilton which she would use for the rest of her life. Hamilton's public career was now at its height and during their visit to England he was inducted into the Privy Council. Shortly after the ceremony, George Romney painted his last portrait of Emma from life, The Ambassadress, after which he plunged into a deep depression and drew a series of frenzied sketches of Emma. The newly married couple returned to Naples after two days. After the marriage, Greville transferred the cost of Emma Carew(Lady Hamilton's daughter)'s upkeep to Sir William, and suggested that he might move her to an establishment befitting the stepdaughter of an envoy. However, Sir William preferred to forget about her for a while. Lady Hamilton became a close friend of Queen Maria Carolina, wife of Ferdinand I of Naples and sister of French Queen Marie Antoinette, and soon acquired fluency in both French and Italian. She was also a talented amateur singer. She sang one of the solo parts of Joseph Haydn's Nelson Mass and entertained guests at her home. At one point, the Royal Opera in Madrid tried to engage her for a season, in competition with their star, Angelica Catalani, but that offer was turned down. Sharing Sir William Hamilton's enthusiasm for classical antiquities and art, she developed what she called her "Attitudes"—tableaux vivants in which she portrayed sculptures and paintings before British visitors. Emma developed the attitudes, also known as mimoplastic art, by using Romney's idea of combining classical poses with modern allure as the basis for her act. Emma had her dressmaker make dresses modelled on those worn by peasant islanders in the Bay of Naples, and the loose-fitting garments she often wore when modelling for Romney. She would pair these tunics with a few large shawls or veils, draping herself in folds of cloth and posing in such a way as to evoke popular images from Greco-Roman mythology. This cross between postures, dance and acting was first revealed to guests in the spring of 1787 by Sir William at his home in Naples. It formed a sort of charade, with the audience guessing the names of the classical characters and scenes Emma portrayed. With the aid of her shawls, Emma posed as various classical figures from Medea to Queen Cleopatra, and her performances charmed aristocrats, artists such as Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun, writers—including the great Johann Wolfgang von Goethe—and kings and queens alike, setting off new dance trends across Europe and starting a fashion for a draped Grecian style of dress. "Attitudes" were taken up by several other (female) artists, among them Ida Brun from Denmark, who became Emma's successor in the new art form. The famed sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen admired her art. As wife of the British Envoy, Emma welcomed Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount(who had been married to Fanny Nisbet for about 6 years at that point) after his arrival in Naples on 10 September 1793, when he came to gather reinforcements against the French. She is described in 1797 in the diary of 18-year-old Elizabeth Wynne as "a charming woman, beautiful and exceedingly good humoured and amiable." When he set sail for Sardinia on 15 September after only 5 days in Naples, it was clear that he had already fallen a little in love. After four years of marriage, Emma had despaired of having children with Sir William, although she wrote of him as "the best husband and friend". It seems likely that he was sterile. She once again tried to persuade him to allow her daughter to come and live with them in the Palazzo Sessa as her mother Mrs Cadogan's niece, but he refused this as well as her request to make enquiries in England about suitors for the young Emma. Horatio Nelson returned to Naples five years later, on 22 September 1798, now a living legend, after his victory at the Battle of the Nile in Aboukir. By this time, Nelson's adventures had prematurely aged him; he had lost an arm and most of his teeth, and was afflicted by coughing spells. Before his arrival, Emma had written a letter passionately expressing her admiration for him. Nelson even wrote effusively of Emma to his increasingly estranged wife. Emma and Sir William escorted Nelson to their home, the Palazzo Sessa. Emma nursed Nelson under her husband's roof and arranged a party with 1,800 guests to celebrate his 40th birthday on 29 September. After the party, Emma became Nelson's secretary, translator and political facilitator. They soon fell in love and began an affair. Hamilton showed admiration and respect for Nelson, and vice versa; the affair was tolerated. By November, gossip from Naples about their affair reached the English newspapers. Emma Hamilton and Horatio Nelson were famous. Emma had by then become not only a close personal friend of Queen Maria Carolina, but had developed into an important political influence. She advised the Queen on how to react to the threats from the French Revolution. Maria Carolina's sister Marie Antoinette had fallen a victim to the Revolution. In 1799, Naples was the scene of a strange revolution led by members of the aristocracy; the common people did not agree with the revolution. The French troops were not welcome, but the royal family fled to Sicily. From here Nelson tried to help the royal family put down the revolutionaries. He had no support from the British government. Emma played an important role in helping to put an end to the revolution when she arrived off Naples with Nelson's fleet on 24 June 1799. She acted as a go-between, conveying messages from the queen to Nelson and from Nelson to the queen. Nelson's recall to Britain shortly afterwards coincided with the government finally granting Hamilton's request for relief from his post in Naples. Emma must have become pregnant around April 1800. Nelson, Emma, her mother and Sir William travelled together—taking the longest possible route back to Britain via Central Europe (hearing the Missa in Angustiis by Joseph Haydn, now known as the "Nelson Mass", in Vienna in 1800), and eventually arriving in Yarmouth to a hero's welcome on 6 November 1800. Upon arrival in London on 8 November, the three of them took suites at Nerot's Hotel. Lady Nelson and Nelson's father arrived and they all dined at the hotel, with Fanny Nelson deeply unhappy to see Emma pregnant. The affair soon became public knowledge, and to the delight of the newspapers, Fanny did not accept the affair as placidly as Sir William. Nelson contributed to Fanny's misery by being cruel to her when not in Emma's company. Emma was winning the media war at that point, and every fine lady was experimenting with her look. Sir William was mercilessly lampooned in the press, but his sister observed that he doted on Emma and she was very attached to him. The Hamiltons moved into William Beckford's mansion at 22 Grosvenor Square, and Nelson and Fanny took an expensive furnished house at 17 Dover Street, a comfortable walking distance away, until December, when Sir William rented a home at 23 Piccadilly, opposite Green Park. On 1 January, Nelson's promotion to vice admiral was confirmed and he prepared to go to sea on the same night. Infuriated by Fanny's ultimatum to choose between her and his mistress, Nelson chose Emma and decided to take steps to formalise separation from his wife. He never saw her again, after being hustled out of town by an agent. While he was at sea, Nelson and Emma exchanged many letters, using a secret code to discuss Emma's condition. Emma kept her first daughter Emma Carew's existence a secret from Nelson, while Sir William continued to provide for her. Emma gave birth to Nelson's daughter Horatia, on 29 January 1801 at 23 Piccadilly, who was taken soon afterwards to a Mrs Gibson for care and hire of a wet nurse. On 1 February, Emma made a spectacular appearance at a concert at the house of the Duke of Norfolk in St James' Square, and Emma worked hard to keep the press onside. Soon after this, the Prince of Wales (later King George IV) became infatuated with Emma, leading Nelson to be consumed by jealousy, and inspiring a remarkable letter by Sir William to Nelson, assuring him that she was being faithful. In late February, Nelson returned to London and met his daughter at Mrs Gibson's. Nelson's family were aware of the pregnancy, and his clergyman brother Rev. William Nelson wrote to Emma praising her virtue and goodness. Nelson and Emma continued to write letters to each other when he was away at sea, and she kept every one. By the autumn of the same year, upon Emma's advice, Nelson bought Merton Place, a small ramshackle house at Merton, near Wimbledon, for £9,000, borrowing money from his friend Davison. He gave her free rein with spending to improve the property, and her vision was to transform the house into a celebration of his genius. There they lived together openly, with Sir William and Emma's mother, in a ménage à trois that fascinated the public. Emma turned herself to winning over Nelson's family, nursing his 80-year-old father Edmund for 10 days at Merton, who loved her and thought of moving in with them, but could not bear to leave his beloved Norfolk. Emma also made herself useful to Nelson's sisters Kitty (Catherine), and Susanna by helping to raise their children and to make ends meet. Also around this time, Emma finally told Nelson about her daughter Emma Carew, now known as Emma Hartley, and he invited her to stay at Merton and soon grew fond of "Emma's relative" and assumed responsibility for upkeep of young Emma at this time. After the Treaty of Amiens on 25 March 1802, Nelson was released from active service, but wanted to keep his new-found position in society by maintaining an aura of wealth, and Emma worked hard to live up to this dream. The newspapers reported on their every move, looking to Emma to set fashions in dress, home decoration and even dinner party menus. By the autumn of 1803, Sir William's health was declining, at the same time that the peace with France was disintegrating. Soon afterwards, Sir William collapsed at 23 Piccadilly and on 6 April died in Emma's arms. Charles Greville was the executor of the estate and he instructed her to leave 23 Piccadilly, but for the sake of respectability, she had to keep an address separate from Nelson's and so moved into 11 Clarges Street, not far away, a couple of months later. Nelson had been offered the position of Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, and they rushed to have Horatia christened at Marylebone Parish Church before he left, by now Emma was pregnant with their second child, although neither knew it at this time. She was desperately lonely, preoccupied with attempting to turn Merton Place into the grand home Nelson desired, suffering from several ailments and frantic for his return. The second child, a girl, died about 6 weeks after her birth in early 1804, and Horatia also fell ill at her home with Mrs Gibson on Titchfield Street. Emma kept the infant's death a secret from the press, kept her deep grief from Nelson's family and found it increasingly difficult to cope alone. She reportedly distracted herself by gambling, and succumbed to binges of heavy drinking and eating and spending lavishly. Emma received several marriage proposals during 1804, all wealthy men, but she was still in love with Nelson and believed that he would become wealthy with prize money and leave her rich in his will, and she refused them all. She continued to entertain and help Nelson's relatives. Nelson urged her to keep Horatia at Merton, and when his return seemed imminent in 1804, Emma ran up bills on furnishing and decorating Merton. Five-year-old Horatia came to live at Merton in May 1805. After a brief visit to England in August 1805, Nelson once again had to return to service. On the ship, he wrote a note intended as a codicil to his will requesting that, in return for his legacy to King and Country that they should give Emma "ample provision to maintain her rank in life", and that his "adopted daughter, Horatia Nelson Thompson...use in future the name of Nelson only". On 21 October 1805, Nelson's fleet defeated a joint Franco-Spanish naval force at the Battle of Trafalgar. Nelson was seriously wounded during the battle and died three hours later. When the news of his death arrived in London, a messenger was sent to Merton Place to bring the news to Lady Hamilton. She later recalled, Emma lay in bed prostrate with grief for many weeks, often receiving visitors in tears. It was some weeks before she heard that Nelson's last words were of her and that he had begged the nation to take care of her and Horatia. Emma relied on Nelson's sisters (Kitty Matcham and Susanna Bolton) for moral support and company. Like her, the Boltons and Matchams had spent lavishly in expectation of Nelson's victorious return, and Emma gave them and other of his friends and relations money. Nelson's will was read in November 1805; Nelson's brother William inherited his entire estate except for Merton, as well as his bank accounts and possessions. The government had made William an Earl and his son Horatio (aka Horace) a Viscount - the titles Nelson had aspired to - and now he was also Duke of Bronte. Emma received £2000, Merton, and £500 per annum from the Bronte estate - much less than she had when Nelson was alive, and not enough to maintain Merton. In spite of Nelson's status as a national hero, the instructions he left to the government to provide for Emma and Horatia were ignored; they also ignored his wishes that she should sing at his funeral. The funeral was lavish, costing the state £14,000, but Emma was excluded. Only the men of the Bolton and Matcham family were invited, and Emma spent the day with her family and the women. She gave both families dinner and breakfast and accommodated the Boltons. After the funeral, the begging letters began. William would not help, so everybody turned to Emma. Lord Grenville sent the codicil to Nelson's will to his solicitor with a note saying that nothing could be done; instead, the Boltons and Matchams received £10,000 each (but still left their adolescent daughters with Emma to educate), while William was awarded £100,000 to buy an estate called Trafalgar, as well as £5000 for life. Relations between William and Emma became strained and he refused to give her the £500 pension due to her. She spent 1806 to 1808 keeping up the act, continuing to spend on parties and alterations to Merton to make it a monument to Nelson. Goods that Nelson had ordered arrived and had to be paid for. The annual annuity of £800 from Sir William's estate was not enough to pay off the debts and keep up the lifestyle, and Emma fell deeply into debt. She moved from Clarges Street to a cheaper home at 136 Bond Street, but could not bring herself to relinquish Merton. Emma hosted and employed James Harrison for 6 months to write a two-volume Life of Nelson, which made it clear that Horatia was his child. She continued to entertain at Merton, including the Prince of Wales and the Dukes of Sussex and Clarence, but no favours were returned by the royals. Within three years, Emma was more than £15,000 in debt. In June 1808, Merton failed to sell at auction and was eventually sold in April 1809. However, her lavish spending continued, and a combination of this and the steady depletion of funds due to people fleecing her meant that she remained in debt, although unbeknownst to most people. For most of 1811 and 1812 she was in a virtual debtors' prison. In early 1813 she petitioned the Prince of Wales, the government and friends, but all of her requests failed and she was obliged to auction off many of her possessions, including many Nelson relics, at low prices. However she continued to borrow money to keep up appearances. Public opinion turned against her after the Letters of Lord Nelson to Lady Hamilton were published in April 1814. Emma was anxious to leave the country, but owing to the risk of arrest if she travelled on a normal ferry, she and Horatia hid from her creditors for a week before boarding a private vessel bound for Calais on 1 July 1814, with £50 in her purse. Initially taking apartments at the expensive Dessein's Hotel, she initially kept up a social life and fine dining by relying on creditors. But soon she was deeply in debt and suffering from longstanding health problems, including stomach pains, nausea and diarrhoea. Emma started drinking heavily and taking laudanum. She died on 15 January 1815, aged 49. Emma was buried in Calais on 21 January in public ground outside the town, with her friend Joshua Smith paying for the modest funeral at the Catholic church. Her grave was subsequently lost due to wartime destruction, but in 1994 a dedicated group unveiled the memorial which stands today in the Parc Richelieu in her honour. Henry Cadogan cared for the 14-year-old Horatia in the aftermath of Emma's death. Horatia subsequently married the Rev. Philip Ward, had ten children (the first of whom was named Horatio Nelson) and lived until 1881. Horatia never publicly acknowledged that she was the daughter of Emma Hamilton. Emma Hamilton is generally known by the courtesy title of "Lady Hamilton", to which she was entitled from 1791 as the wife and then widow of Sir William Hamilton. In 1800, she became "Dame Emma Hamilton", a title she held in her own right as a female member of the Order of Malta. This was an unusual honour, awarded to Lady Hamilton by the then Grand Master of the Order, Tsar Paul, in recognition of her role in the defence of the island of Malta against the French. Subsequently, she used her new title in formal circumstances, and was also acknowledged as "Dame Emma Hamilton" in official British contexts; most notably, this was the title under which she was formally granted her own coat of arms by the English College of Arms in 1806, Per pale Or and Argent, three Lions rampant Gules, on a chief Sable, a Cross of eight points of the second. The lions evidently refer to her maiden surname of Lyons, while the addition of the Maltese Cross, which has puzzled heraldic scholars unaware of her connection to the Order, is recognisable as an honourable augmentation referring to her damehood. In popular cultureEmma Hamilton was widely recognized in popular culture in different forms

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|