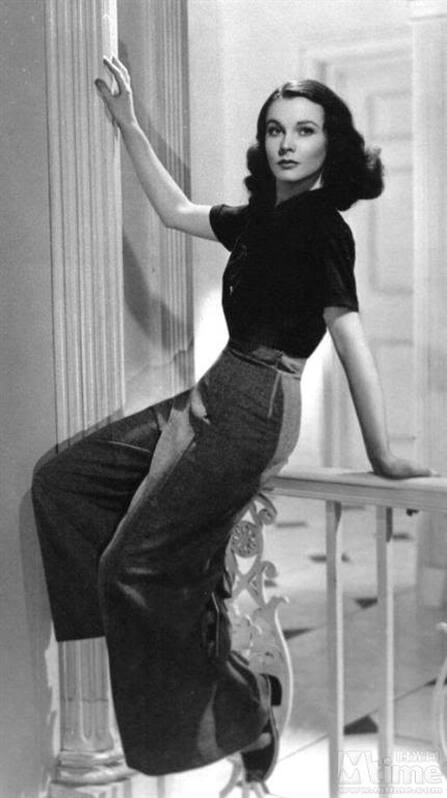

ProfileVivien Leigh (5 November 1913 – 8 July 1967; born Vivian Mary Hartley) was a British stage and film actress. She won the Academy Award for Best Actress twice, for her definitive performances as Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939) and Blanche DuBois in the film version of A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), a role she had also played on stage in London's West End in 1949. She also won a Tony Award for her work in the Broadway musical version of Tovarich (1963). After completing her drama school education, Leigh appeared in small roles in four films in 1935 and progressed to the role of heroine in Fire Over England (1937). Lauded for her beauty, Leigh felt that her physical attributes sometimes prevented her from being taken seriously as an actress. Despite her fame as a screen actress, Leigh was primarily a stage performer. During her 30-year career, she played roles ranging from the heroines of Noël Coward and George Bernard Shaw comedies to classic Shakespearean characters such as Ophelia, Cleopatra, Juliet, and Lady Macbeth. Later in life, she performed as a character actress in a few films. At the time, the public strongly identified Leigh with her second husband, Laurence Olivier, who was her spouse from 1940 to 1960. Leigh and Olivier starred together in many stage productions, with Olivier often directing, and playing in three films. She earned a reputation for being difficult to work with, and for much of her adult life, she had bipolar disorder, as well as recurrent bouts of chronic tuberculosis, which was first diagnosed in the mid-1940s and ultimately killed her at the age of 53. Although her career had periods of inactivity, in 1999 the American Film Institute ranked Leigh as the 16th greatest female movie star of classic Hollywood cinema. BiographyLeigh was born Vivian Mary Hartley on 5 November 1913 in British India on the campus of St. Paul's School in Darjeeling, Bengal Presidency. She was the only child of Ernest Richard Hartley, a British broker, and his wife, Gertrude Mary Frances who were married in 1912 in Kensington, London. At the age of three, young Vivian made her first stage appearance for her mother's amateur theatre group, reciting "Little Bo Peep". Gertrude Hartley tried to instill an appreciation of literature in her daughter and introduced her to the works of Hans Christian Andersen, Lewis Carroll and Rudyard Kipling, as well as stories of Greek mythology and Indian folklore. At the age of six, Vivian was sent by her mother from Loreto Convent, Darjeeling, to the Convent of the Sacred Heart (now Woldingham School) then situated in Roehampton, southwest London. One of her friends there was future actress Maureen O'Sullivan, two years her senior. She was removed from the school by her father, and travelling with her parents for four years, she attended schools in Europe, notably in Dinard (Brittany, France), Biarritz (France), the Sacred Heart in San Remo on the Italian Riviera, and in Paris, becoming fluent in both French and Italian. The family returned to Britain in 1931. She attended A Connecticut Yankee, one of O'Sullivan's films playing in London's West End, and told her parents of her ambitions to become an actress. Shortly after, her father enrolled Vivian at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in London. Vivian met Herbert Leigh Holman, known as Leigh Holman, a barrister 13 years her senior, in 1931. Despite his disapproval of "theatrical people", they married on 20 December 1932 and she terminated her studies at RADA, her attendance and interest in acting having already waned after meeting Holman. On 12 October 1933 in London, she gave birth to a daughter, Suzanne, later Mrs. Robin Farrington. Leigh's friends suggested she take a small role as a schoolgirl in the film Things Are Looking Up, which was her film debut, albeit uncredited as an extra. She engaged an agent, John Gliddon, who believed that "Vivian Holman" was not a suitable name for an actress. After rejecting his many suggestions, she took "Vivian Leigh" as her professional name. Gliddon recommended her to Alexander Korda as a possible film actress, but Korda rejected her as lacking potential. She was cast in the play The Mask of Virtue, directed by Sidney Carroll in 1935, and received excellent reviews, followed by interviews and newspaper articles. John Betjeman, the future poet laureate, described her as "the essence of English girlhood". Korda attended her opening night performance, admitted his error, and signed her to a film contract. In the autumn of 1935 and at Leigh's insistence, John Buckmaster introduced her to Laurence Olivier at the Savoy Grill, where he and his first wife Jill Esmond dined regularly after his performance in Romeo and Juliet. Olivier had seen Leigh in The Mask of Virtue earlier in May and congratulated her on her performance. Olivier and Leigh began an affair while acting as lovers in Fire Over England (1937), while both were still married. Despite her relative inexperience, Leigh was chosen to play Ophelia to Olivier's Hamlet in an Old Vic Theatre production staged at Elsinore, Denmark. They began living together, as their respective spouses had each refused to grant either of them a divorce. Under the moral standards then enforced by the film industry, their relationship had to be kept from public view. During this period, Leigh read the Margaret Mitchell novel Gone with the Wind and instructed her American agent to recommend her to David O. Selznick, who was planning a film version. According to legend, Myron Selznick, David O. Selznick‘s brother took Vivien Leigh and Lawrence Olivier to the set where the burning of the Atlanta Depot scene was being filmed and stage-managed an encounter, where he introduced Leigh, derisively addressing his younger brother, "Hey, genius, meet your Scarlett O'Hara." The following day, Leigh read a scene for Selznick, who organized a screen test with director George Cukor who praised Leigh's "incredible wildness". She secured the role of Scarlett soon after. Filming proved difficult for Leigh. Cukor was dismissed and replaced by Victor Fleming, with whom Leigh frequently quarrelled. Leigh was sometimes required to work seven days a week, often late into the night, which added to her distress, and she missed Olivier, who was working in New York City. Gone with the Wind brought Leigh immediate attention and fame. The film won 10 Academy Awards including a Best Actress award for Leigh, who also won a New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress.  "Miss Leigh's Scarlett has vindicated the absurd talent quest that indirectly turned her up. She is so perfectly designed for the part by art and nature that any other actress in the role would be inconceivable". Film critic Frank Nugent on Vivien Leigh in film Gone with the Wind for The New York Times, 1939 In February 1940, Jill Esmond agreed to divorce Laurence Olivier, and Leigh Holman agreed to divorce Vivien, although they maintained a strong friendship for the rest of Leigh's life. Esmond was granted custody of Tarquin, her son with Olivier. Holman was granted custody of Suzanne, his daughter with Leigh. On 31 August 1940, Olivier and Leigh were married at the San Ysidro Ranch in Santa Barbara, California, in a ceremony attended only by their hosts, Ronald and Benita Colman and witnesses, Katharine Hepburn and Garson Kanin. The Oliviers mounted a stage production of Romeo and Juliet for Broadway, but the critics were hostile in their assessment of the play. The couple had invested almost all of their combined savings of $40,000 in the project, and the failure was a financial disaster for them. The Oliviers then filmed That Hamilton Woman (1941) with Olivier as Horatio Nelson and Leigh as Emma Hamilton. With the United States not yet having entered the war, it was one of several Hollywood films made with the aim of arousing a pro-British sentiment among American audiences. The film was popular in the United States and an outstanding success in the Soviet Union. Winston Churchill arranged a screening for a party that included Franklin D. Roosevelt and, on its conclusion, addressed the group, saying, "Gentlemen, I thought this film would interest you, showing great events similar to those in which you have just been taking part." The Oliviers remained favourites of Churchill, attending dinners and occasions at his request for the rest of his life. With her doctor's approval, Leigh was well enough to resume acting in 1946, starring in a successful London production of Thornton Wilder's The Skin of Our Teeth. In 1947, Olivier was knighted and Leigh accompanied him to Buckingham Palace for the investiture. She became Lady Olivier. After their divorce, according to the style granted to the divorced wife of a knight, she became known socially as Vivien, Lady Olivier. By 1948, Olivier was on the board of directors for the Old Vic Theatre, and he and Leigh embarked on a six-month tour of Australia and New Zealand to raise funds for the theatre. Olivier played the lead in Richard III and also performed with Leigh in The School for Scandal and The Skin of Our Teeth. The tour was an outstanding success and, although Leigh was plagued with insomnia and allowed her understudy to replace her for a week while she was ill, she generally withstood the demands placed upon her, with Olivier noting her ability to "charm the press". By the end of the tour, both were exhausted and ill. Later, Olivier would observe that he "lost Vivien" in Australia. The success of the tour encouraged the Oliviers to make their first West End appearance together, performing the same works with one addition, Antigone, included at Leigh's insistence because she wished to play a role in a tragedy. The Oliviers returned to Britain in March 1943, and Leigh toured through North Africa that same year as part of a revue for the armed forces stationed in the region. She reportedly turned down a studio contract worth $5,000 a week in order to volunteer as part of the war effort.Leigh performed for troops before falling ill with a persistent cough and fevers. In 1944, she was diagnosed as having tuberculosis in her left lung and spent several weeks in hospital before appearing to have recovered. Leigh was filming Caesar and Cleopatra (1945) when she discovered she was pregnant, then had a miscarriage. Leigh temporarily fell into a deep depression that hit its low point, with her falling to the floor, sobbing in an hysterical fit. This was the first of many major bipolar disorder breakdowns. Olivier later came to recognise the symptoms of an impending episode—several days of hyperactivity followed by a period of depression and an explosive breakdown, after which Leigh would have no memory of the event, but would be acutely embarrassed and remorseful. Leigh next was cast the role of Blanche DuBois in the West End stage production of Tennessee Williams's A Streetcar Named Desire, and Olivier was contracted to direct. After 326 performances, Leigh finished her run, and she was soon assigned to reprise her role as Blanche DuBois in the film version of the play. Leigh's performance in A Streetcar Named Desire won glowing reviews, as well as a second Academy Award for Best Actress, a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for Best British Actress, and a New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress.Tennessee Williams commented that Leigh brought to the role "everything that I intended, and much that I had never dreamed of". Leigh herself had mixed feelings about her association with the character; in later years, she said that playing Blanche DuBois "tipped me over into madness". In January 1953, Leigh travelled to Ceylon to film Elephant Walk with Peter Finch. Shortly after filming commenced, she had a nervous breakdown and Paramount Pictures replaced her with Elizabeth Taylor. Olivier returned her to their home in Britain, where, between periods of incoherence, Leigh told him she was in love with Finch and had been having an affair with him. Leigh's romantic relationship with Finch began in 1948, and waxed and waned for several years, ultimately flickering out as her mental condition deteriorated. In 1958, considering her marriage to be over, Leigh began a relationship with actor Jack Merivale, who knew of Leigh's medical condition and assured Olivier that he would care for her. In 1960, she and Olivier divorced and Olivier soon married actress Joan Plowright. In his autobiography, Olivier discussed the years of strain they had experienced because of Leigh's illness: "Throughout her possession by that uncannily evil monster, manic depression, with its deadly ever-tightening spirals, she retained her own individual canniness—an ability to disguise her true mental condition from almost all except me, for whom she could hardly be expected to take the trouble." Though she was still beset by bouts of depression, she continued to work in the theatre and, in 1963, won a Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical for her role in Tovarich. Leigh's last screen appearance in Ship of Fools was both a triumph and emblematic of her illnesses that were taking root. Leigh's performance was tinged by paranoia and resulted in outbursts that marred her relationship with other actors. Leigh won the L'Étoile de Cristal for her performance in a leading role in Ship of Fools. In May 1967, Leigh was rehearsing to appear with Michael Redgrave in Edward Albee's A Delicate Balance when her tuberculosis resurfaced. Following several weeks of rest, she seemed to recover. On the night of 7 July 1967, Jack Merivale left her as usual at their Eaton Square flat to perform in a play, and he returned home just before midnight to find her asleep. About 30 minutes later (by now 8 July), he entered the bedroom and discovered her body on the floor. She had been attempting to walk to the bathroom and, as her lungs filled with liquid, she collapsed and suffocated. Merivale first contacted her family and later was able to reach Olivier, who was receiving treatment for prostate cancer in a nearby hospital. In his autobiography, Olivier described his "grievous anguish" as he immediately travelled to Leigh's residence, to find that Merivale had moved her body onto the bed. Olivier paid his respects, and "stood and prayed for forgiveness for all the evils that had sprung up between us", before helping Merivale make funeral arrangements; Olivier stayed until her body was removed from the flat. Her death was publicly announced on 8 July, and the lights of every theatre in central London were extinguished for an hour. A Catholic service for Leigh was held at St. Mary's Church, Cadogan Street, London. Her funeral was attended by the luminaries of British stage and screen. According to the provisions of her will, Leigh was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium and her ashes were scattered on the lake at her summer home, Tickerage Mill, near Blackboys, East Sussex, England. A memorial service was held at St Martin-in-the-Fields, with a final tribute read by John Gielgud. In 1968, Leigh became the first actress honoured in the United States, by "The Friends of the Libraries at the University of Southern California". The ceremony was conducted as a memorial service, with selections from her films shown and tributes provided by such associates as George Cukor, who screened the tests that Leigh had made for Gone with the Wind, the first time the screen tests had been seen in 30 years. Further interestArticles Websites

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|