|

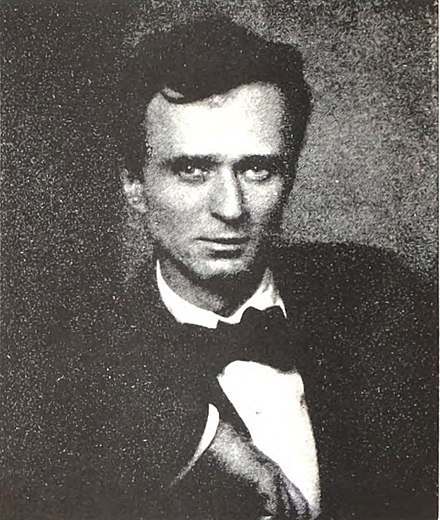

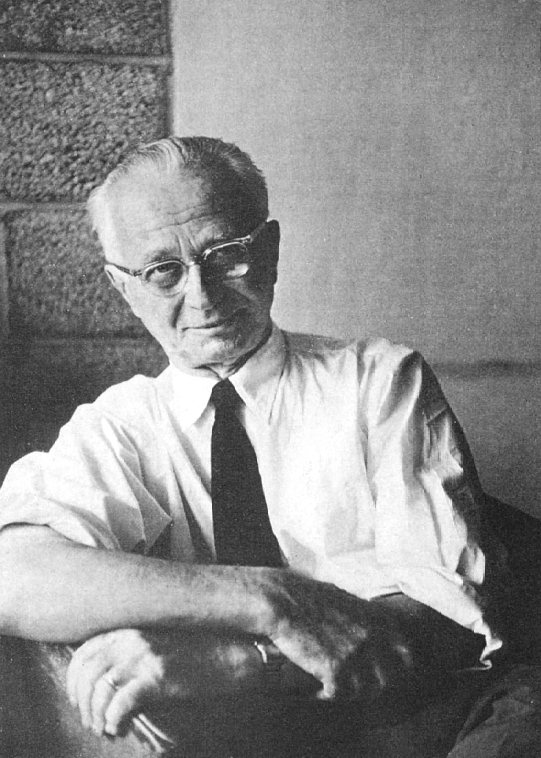

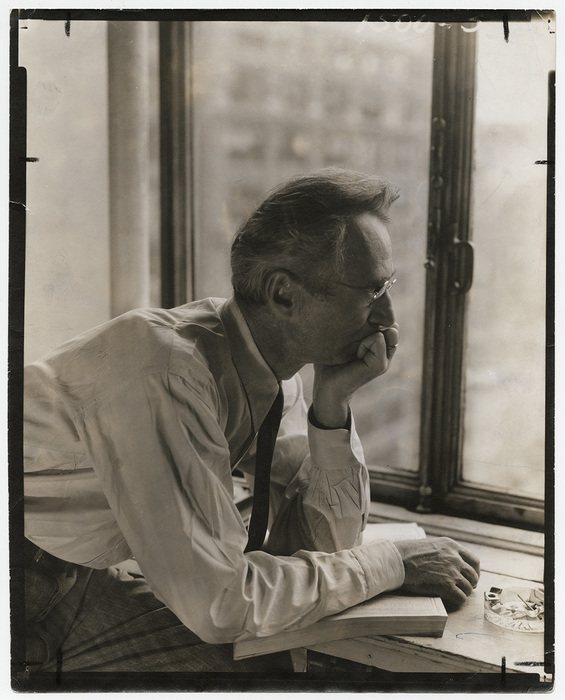

Edward Jean Steichen (March 27, 1879 – March 25, 1973) was a Luxembourgish American photographer, painter, and curator, renowned as one of the most prolific and influential figures in the history of photography. Steichen was credited with transforming photography into an art form. His photographs appeared in Alfred Stieglitz's groundbreaking magazine Camera Work more often than anyone else during its publication run from 1903 to 1917. Stieglitz hailed him as "the greatest photographer that ever lived". As a pioneer of fashion photography, Steichen's gown images for the magazine Art et Décoration in 1911 were the first modern fashion photographs to be published. From 1923 to 1938, Steichen served as chief photographer for the Condé Nast magazines Vogue and Vanity Fair, while also working for many advertising agencies, including J. Walter Thompson. During these years, Steichen was regarded as the most popular and highest-paid photographer in the world. After the United States' entry into World War II, Steichen was invited by the United States Navy to serve as Director of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit. In 1944, he directed the war documentary The Fighting Lady, which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature at the 17th Academy Awards. From 1947 to 1961, Steichen served as Director of the Department of Photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art. While there, he curated and assembled exhibits including The Family of Man, which was seen by nine million people. In 2003, the Family of Man photographic collection was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in recognition of its historical value. In February 2006, a print of Steichen's early pictorialist photograph, The Pond—Moonlight (1904), sold for US$2.9 million—at the time, the highest price ever paid for a photograph at auction. A print of another photograph of the same style, The Flatiron (1904), became the second most expensive photograph ever on November 8, 2022, when it was sold for $12,000,000, at Christie's New York - well above the original estimate of $2,000,000-$3,000,000. BiographyEdward Steichen was born Éduard Jean Steichen on March 27, 1879, in a small house in the village of Bivange, Luxembourg, the son of Jean-Pierre and Marie Kemp Steichen. His parents facing increasingly straitened circumstances and financial difficulties, decided to make a new start and emigrated to the United States when Steichen was eighteen months old. Jean-Pierre Steichen immigrated in 1880, with Marie Steichen bringing the infant Éduard along after Jean-Pierre had settled in Hancock in Michigan's Upper Peninsula copper country. According to noted Steichen biographer, Penelope Niven, the Steichens were “part of a large exodus of Luxembourgers displaced in the late nineteenth century by worsening economic conditions.” Éduard's sister and only sibling, Lilian Steichen, was born in Hancock on May 1, 1883. She would later marry poet Carl Sandburg, whom she met at the Milwaukee Social Democratic Party office in 1907. Her marriage to Sandburg the following year helped forge a life-long friendship and partnership between her brother and Sandburg. By 1889, when Éduard was 10, his parents had saved up enough money to move the family to Milwaukee. There he learned German and English at school, while continuing to speak Luxembourgish at home. In 1894, at fifteen, Steichen began attending Pio Nono College, a Catholic boys' high school, where his artistic talents were noticed. His drawings in particular were said to show promise. He quit high school to begin a four-year lithography apprenticeship with the American Fine Art Company of Milwaukee. After hours, he would sketch and draw, and he began to teach himself painting. Having discovered a camera shop near his work, he visited frequently until he persuaded himself to buy his first camera, a secondhand Kodak box "detective" camera, in 1895. Steichen and his friends who were also interested in drawing and photography pooled their funds, rented a small room in a Milwaukee, WI office building, and began calling themselves the Milwaukee Art Students League. The group hired Richard Lorenz and Robert Schade for occasional lectures. In 1899, Steichen's photographs were exhibited in the second Philadelphia Photographic Salon. Edward Steichen became a U.S. citizen in 1900 and signed the naturalization papers as Edward J. Steichen, but he continued to use his birth name of Éduard until after the First World War. In April 1900, Steichen left Milwaukee for Paris to study art. Clarence H. White thought Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz should meet, and thus produced an introduction letter for Steichen, and Steichen met Stieglitz in New York City in early 1900. In that first meeting, Stieglitz expressed praise for Steichen's background in painting and bought three of Steichen's photographic prints. In 1902, when Stieglitz was formulating what would become Camera Work, he asked Steichen to design the logo for the magazine with a custom typeface. Steichen was the most frequently shown photographer in the journal. Steichen began experimenting with color photography in 1904 and was one of the earliest in the United States to use the Autochrome Lumière process. In 1905, Stieglitz and Steichen created the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, in what had been Steichen's portrait studio; it eventually became known as the 291 Gallery after its address. It presented some of the first American exhibitions of Auguste Rodin, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Constantin Brâncuși. According to author and art historian William A. Ewing, Steichen became one of the earliest "jet setters", constantly moving back and forth between Europe and the U.S. by steamship, in the process cross-pollinating art from Europe to the United States, helping to define photography as an art form, and at the same time widening America's understanding of European art and art in general. Fashion photography began with engravings reproduced from photographs of modishly-dressed actresses by Leopold-Emile Reutlinger, Nadar and others in the 1890s. After high-quality half-tone reproduction of photographs became possible, most credit as pioneers of the genre goes to the French Baron Adolph de Meyer and to Edward Steichen who, borrowing his friend's hand-camera in 1907, candidly photographed dazzlingly-dressed ladies at the Longchamp Racecourse Fashion then was being photographed for newspaper supplements and fashion magazines, particularly by the Frères Séeberger, as it was worn at Paris horse-race meetings by aristocracy and hired models. In 1911, Lucien Vogel, the publisher of Jardin des Modes and La Gazette du Bon Ton, challenged Steichen to promote fashion as a fine art through photography. Steichen took photos of gowns designed by couturier Paul Poiret, which were published in the April 1911 issue of the magazine Art et Décoration. Two were in colour, and appeared next to flat, stylised, yellow-and-black Georges Lepape drawings of accessories, fabrics, and girls. Steichen himself, in his 1963 autobiography, asserted that his 1911 Art et Décoration photographs "were probably the first serious fashion photographs ever made," a generalised claim since repeated by many commentators. What he (and de Meyer) did bring was an artistic approach; a soft-focus, aesthetically retouched Pictorialist style that was distinct from the mechanically sharp images made by his commercial colleagues for half-tone reproduction, and that he and the publishers and fashion designers for whom he worked appreciated as a marketable idealisation of the garment, beyond the exact description of fabrics and buttonholes. After World War I, during which he commanded the photographic division of the American Expeditionary Forces, he gradually reverted to straight photography for his fashion photography and was hired by Condé Nast in 1923 for the extraordinary salary of $35,000 (equivalent to over $500,000 in 2019 value). At the commencement of World War II, Steichen, then in his sixties, had retired as a full-time photographer. He was developing new varieties of delphinium, which in 1936 had been the subject of his first exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, and the only flower exhibition ever held there. When the United States joined the global conflict, Steichen, who had come out of the first World War an Army Colonel, was refused for active service because of his age. Later, invited by the Navy to serve as Director of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit, he was commissioned a Lieutenant-Commander in January 1942. Steichen selected for his unit six officer-photographers from the industry including photographers Wayne Miller and Charles Fenno Jacobs. A collection of 172 silver gelatin photographs taken by the Unit under his leadership is held at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Their war documentary The Fighting Lady, directed by Steichen, won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature at the 17th Academy Awards. In 1942, Steichen curated for the Museum of Modern Art the exhibition Road to Victory, five duplicates of which toured the world. Photographs in the exhibition were credited to enlisted members of the Navy, Coast Guard, and Marine Corps and numbers by Steichen's unit, while many were anonymous and some were made by automatic cameras in Navy planes operated while firing at the enemy. This was followed in January 1945 by Power in the Pacific: Battle Photographs of our Navy in Action on the Sea and In the Sky. Steichen was released from Active Duty (under honorable conditions) on December 13, 1945, at the rank of Captain. For his service during World War II, he was awarded the World War II Victory Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal (with 2 campaign stars), American Campaign Medal, and numerous other awards. In the summer of 1929, Museum of Modern Art director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. had included a department devoted to photography in a plan presented to the Trustees. Though not put in place until 1940, it became the first department of photography in a museum devoted to twentieth-century art and was headed by Beaumont Newhall. On the strength of attendances of his propaganda exhibitions Road to Victory and Power in the Pacific, and precipitating curator Newhall's resignation along with most of his staff, in 1947 Steichen was appointed Director of Photography until 1962, later assisted by Grace M. Mayer, his assistant curator. Steichen as director held a strong belief in the local product, of the "liveness of the melting pot of American photography,’’ and worked to expand and organise the collection, inspiring and recognising the 1950s generation while keeping historical shows to a minimum. Steichen also kept international developments in his scope and held shows and made important acquisitions from Europe and Latin America, occasionally visiting those countries to do so. Three books were published by the Department during his tenure, including Steichen the Photographer. Despite his solid career in photography, Steichen displayed his own work at MoMA—his retrospective, Steichen the Photographer—only after he had already announced his retirement in 1961. Among accomplishments that were to redeem initial resentment at his appointment, Steichen created The Family of Man, a world-touring Museum of Modern Art exhibition that was seen by 9 million visitors and still holds the record for most-visited photography exhibit. Now permanently housed and on continuous display in Clervaux (Luxembourgish: Klierf) Castle in northern Luxembourg, his country of birth, Steichen regarded the exhibition as the "culmination of his career.". Comprising over 500 photos that depicted life, love and death in 68 countries, the prologue for its widely purchased catalogue was written by Steichen's brother-in-law, Carl Sandburg. As had been Steichen's wish, the exhibition was donated to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, his country of birth. Steichen hired John Szarkowski to be his successor at the Museum of Modern Art on July 1, 1962. On December 6, 1963, Steichen was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1968 the Edward Steichen Archive was established in MoMA's Department of Photography. The Museum's then-Director René d’Harnoncourt declared that its function was to "amplify and clarify the meaning of Steichen’s contribution to the art of photography, and to modern art generally.” Creator of the Archive was Grace M. Mayer, who in 1959 started her career as an assistant to the director, Edward Steichen, and who became Curator of Photography in 1962, retiring in 1968. Mayer returned after her retirement to serve in a voluntary capacity as Curator of the Edward Steichen Archive until the mid-1980s to source materials by, about, and related to Steichen. Her detailed card catalogs are housed in the Museum's Grace M. Mayer Papers. Steichen's 90th birthday was marked with a dinner gathering of photographers, editors, writers, and museum professionals at the Plaza Hotel in 1969. The event was hosted by MoMA trustee Henry Allen Moe, and U.S. Camera magazine publisher Tom Maloney. Edward Steichen married Clara E. Smith (1875–1952) in 1903. They had two daughters, Mary Rose Steichen (1904-1998) and Charlotte "Kate" Rodina Steichen (1908-1988). In 1914, Clara accused her husband of having an affair with artist Marion H. Beckett, who was staying with them in France. In 1919, Clara Steichen sued Marion Beckett for having an affair with her husband, but was unable to prove her claims. Clara and Edward Steichen eventually divorced in 1922. Steichen married Dana Desboro Glover in 1923. She died of leukemia in 1957. In 1928, Steichen bought a farm that he called Umpawaug, just outside West Redding, Connecticut. He lived there until his death. In 1960, aged 80, Steichen married 27-year-old Joanna Taub and remained married to her until his death. Edward Steichen died on March 25, 1973, two days before his 94th birthday. After his death, Steichen's farm was made into a park, known as Topstone Park. As of 2018, Topstone Park was open seasonally. His wife Joanna Steichen died on July 24, 2010, in Montauk, New York, aged 77. In 1974 Steichen was posthumously inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum. Further interestArticles  Model Dinarzade in a Dress by Poiret, photo by Edward Steichen, 1924 Model Dinarzade in a Dress by Poiret, photo by Edward Steichen, 1924

0 Comments

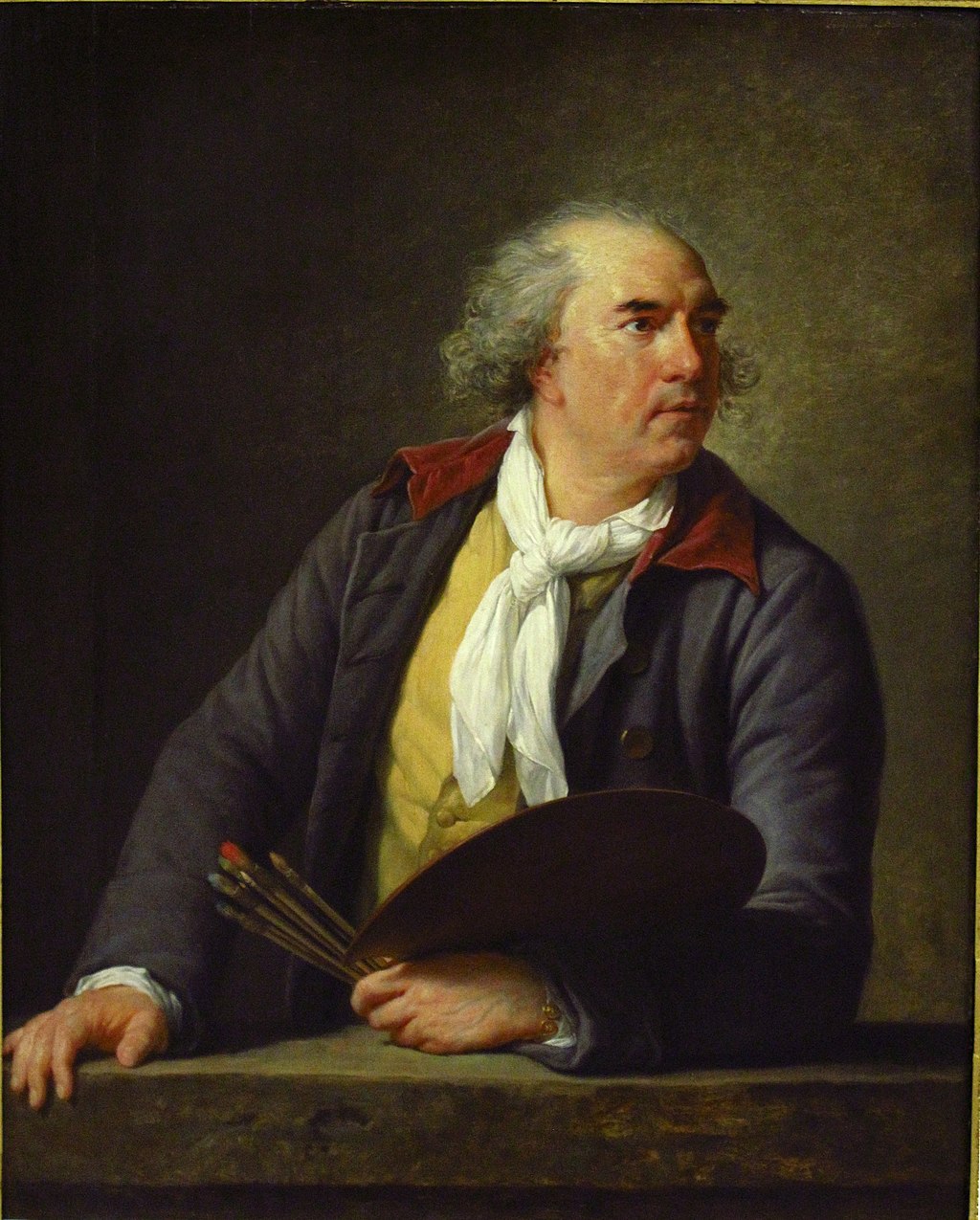

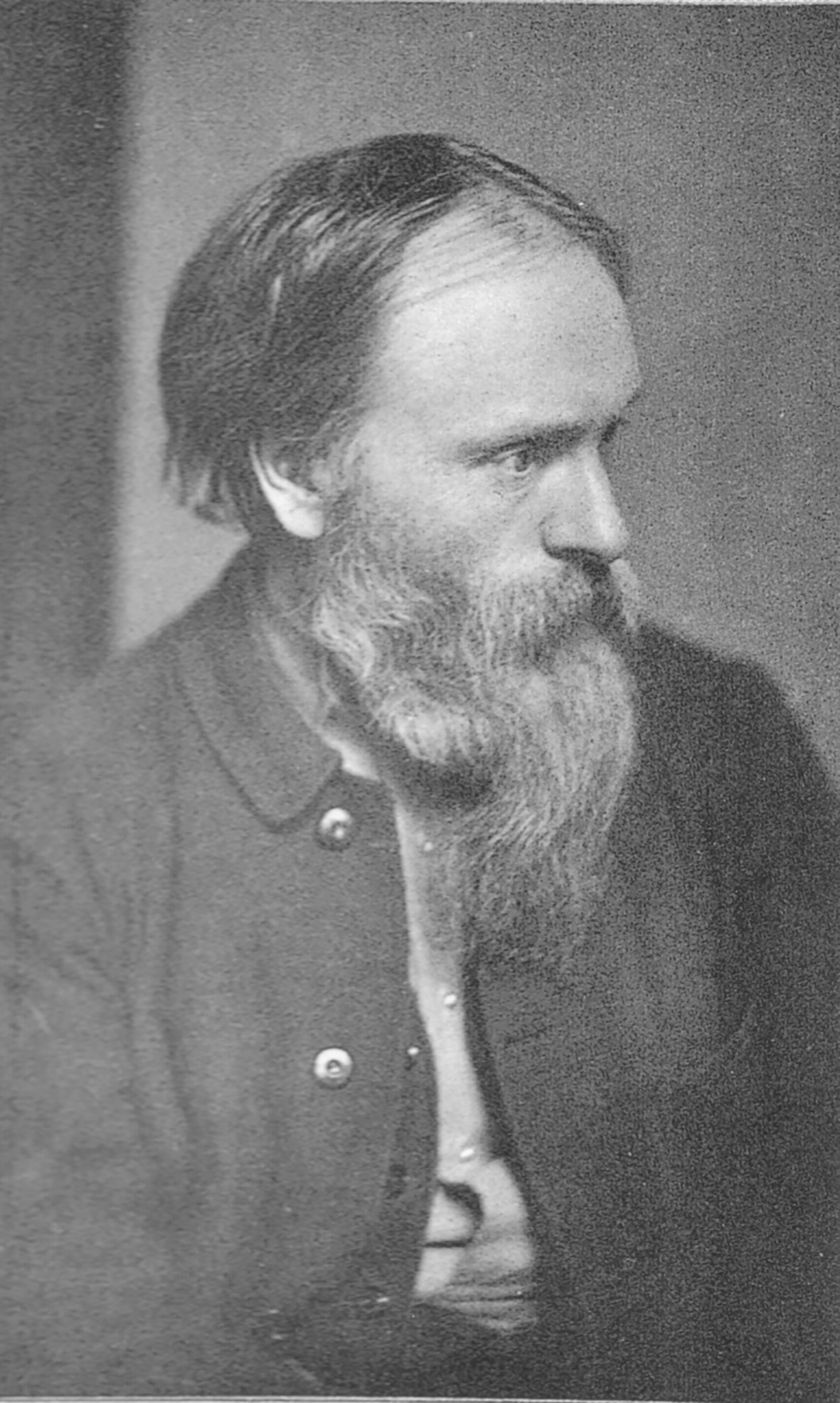

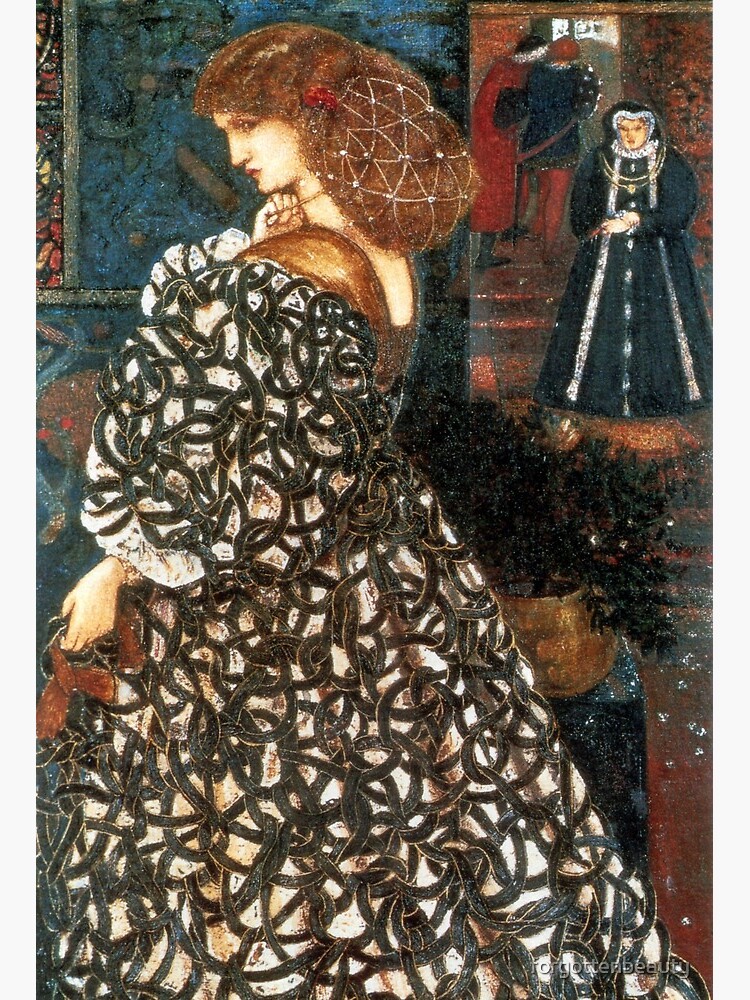

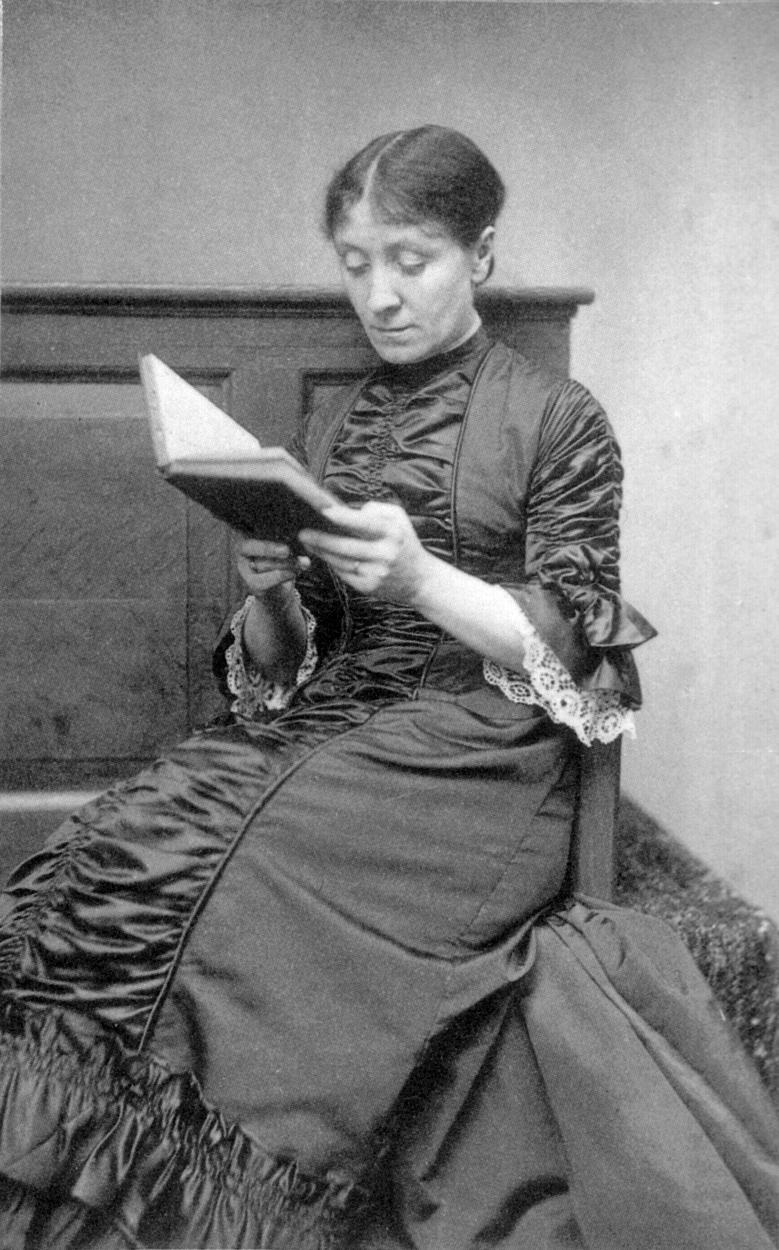

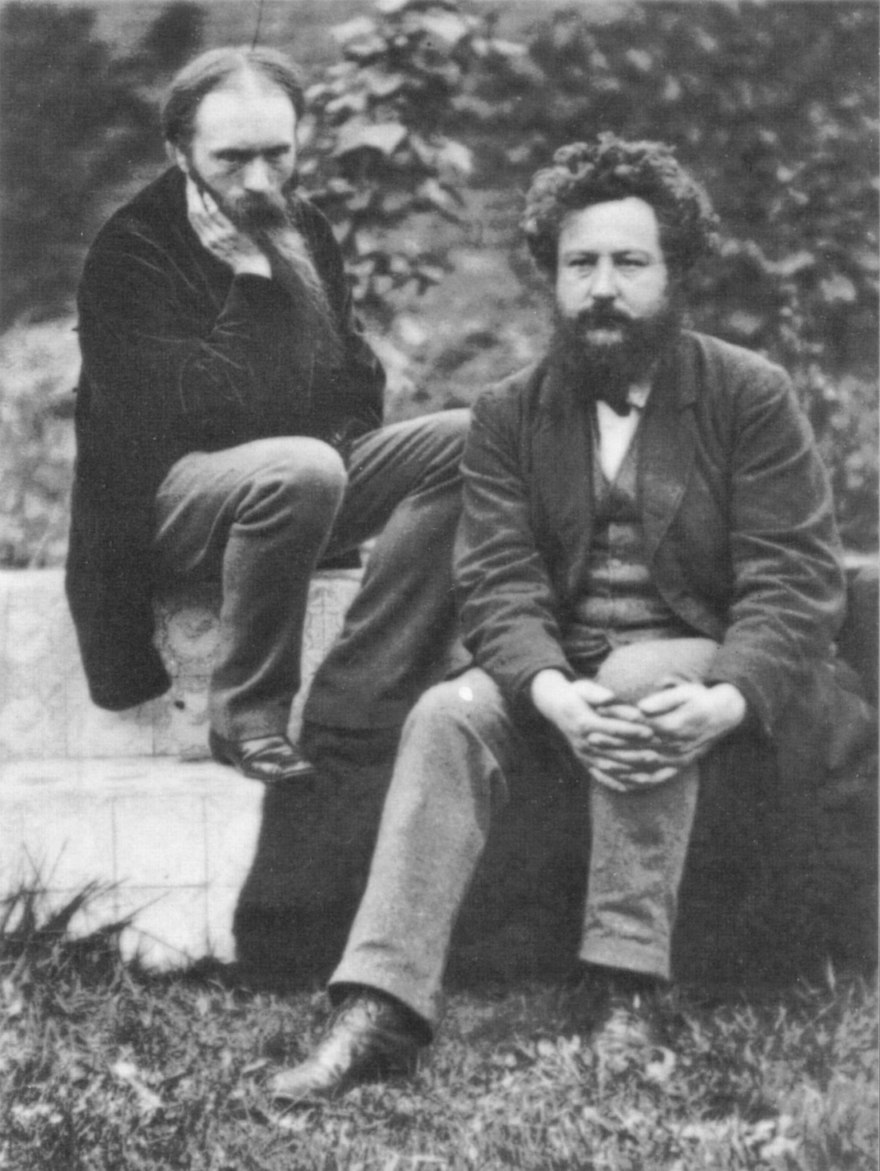

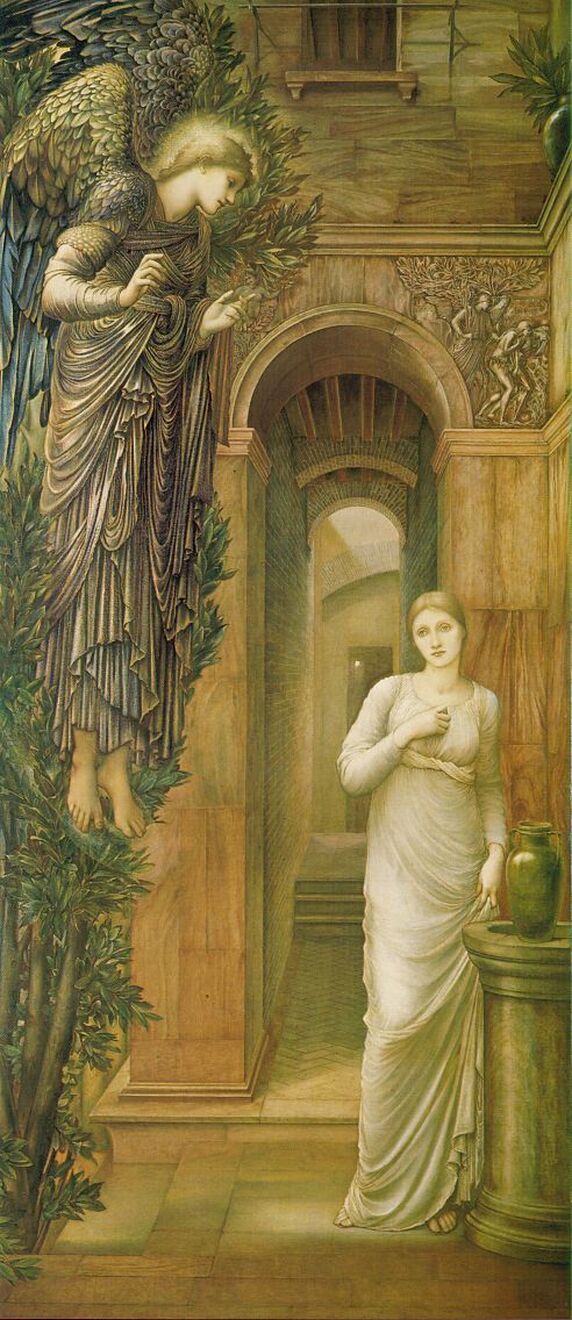

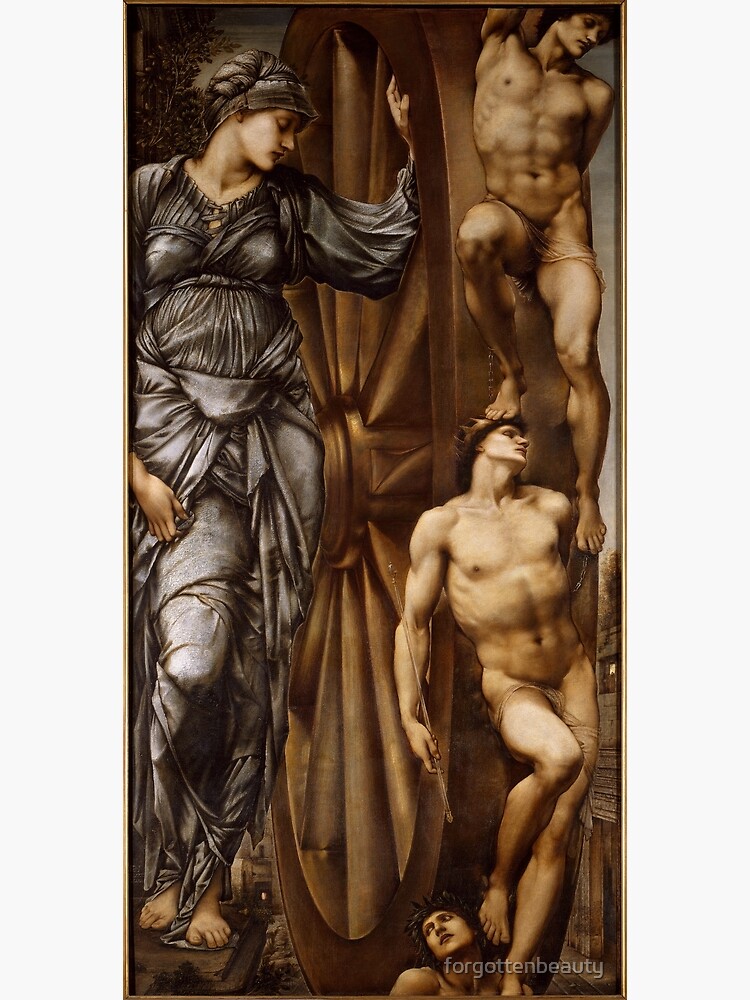

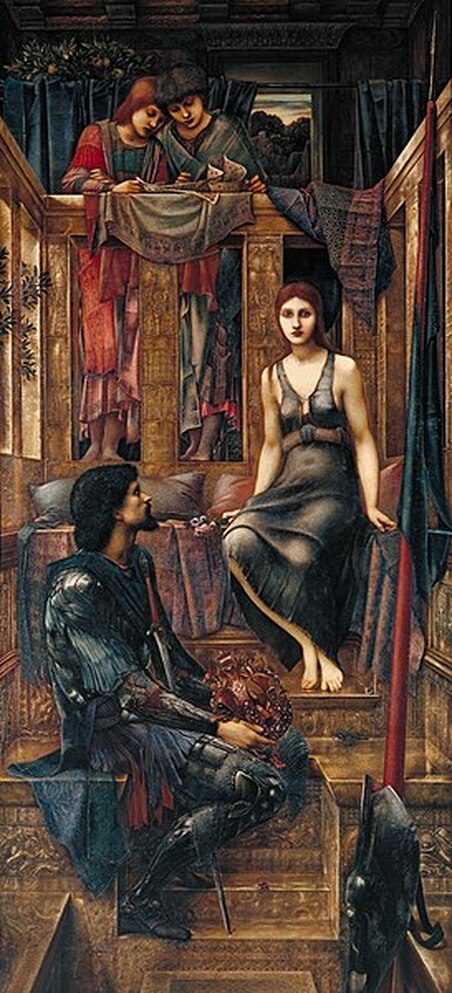

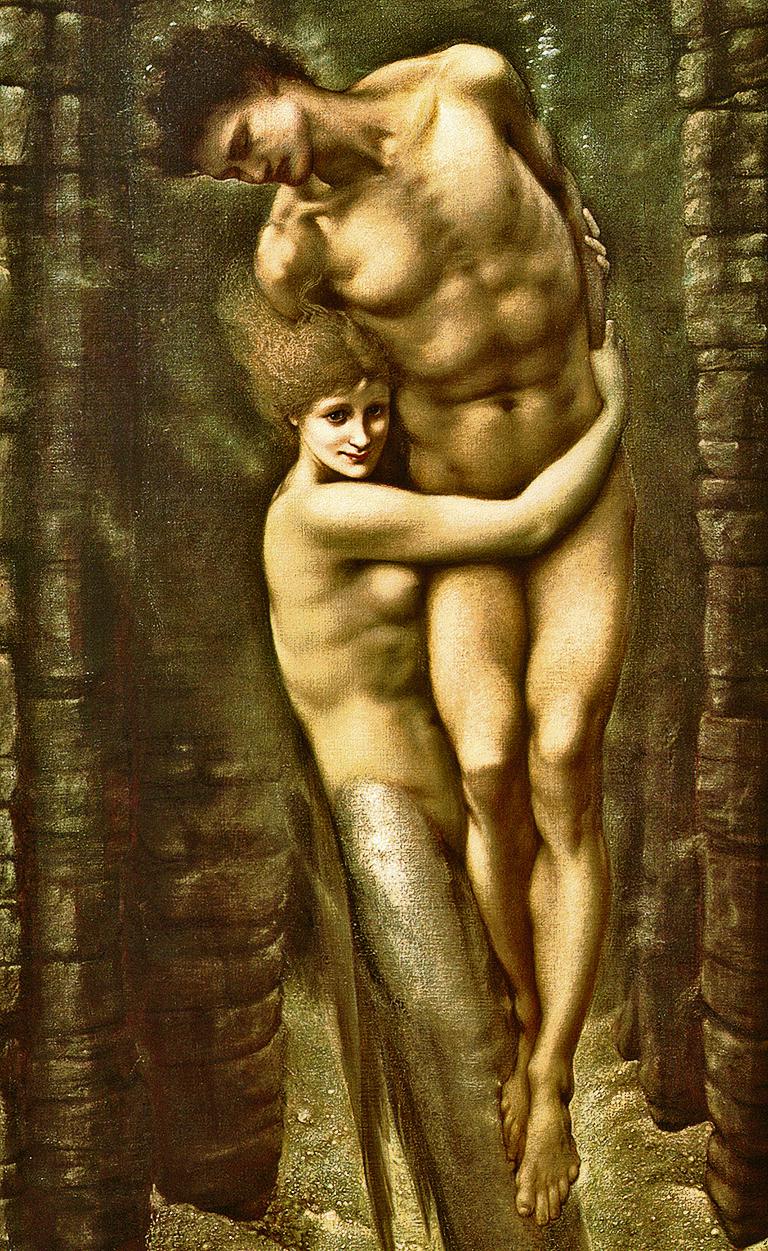

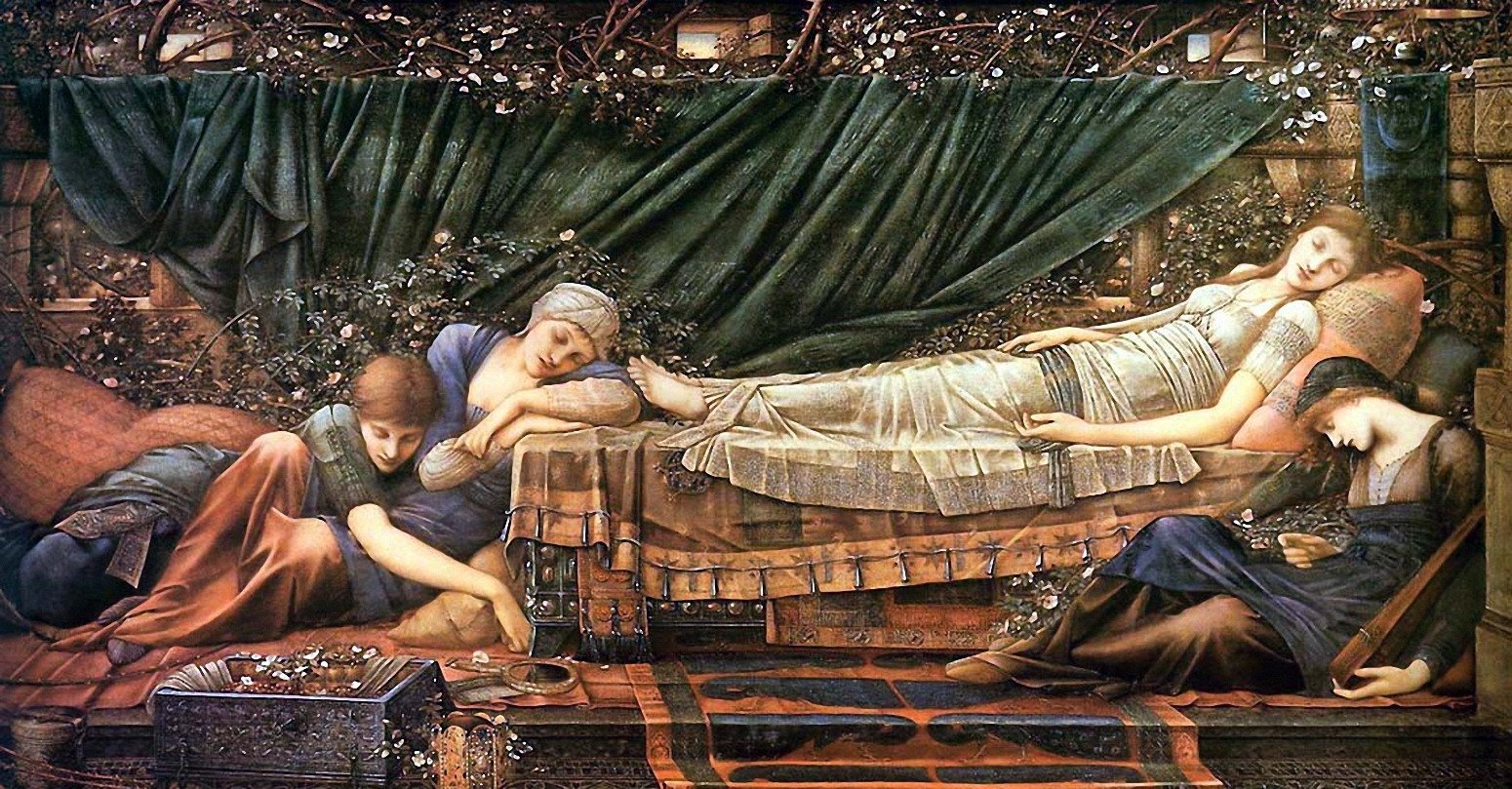

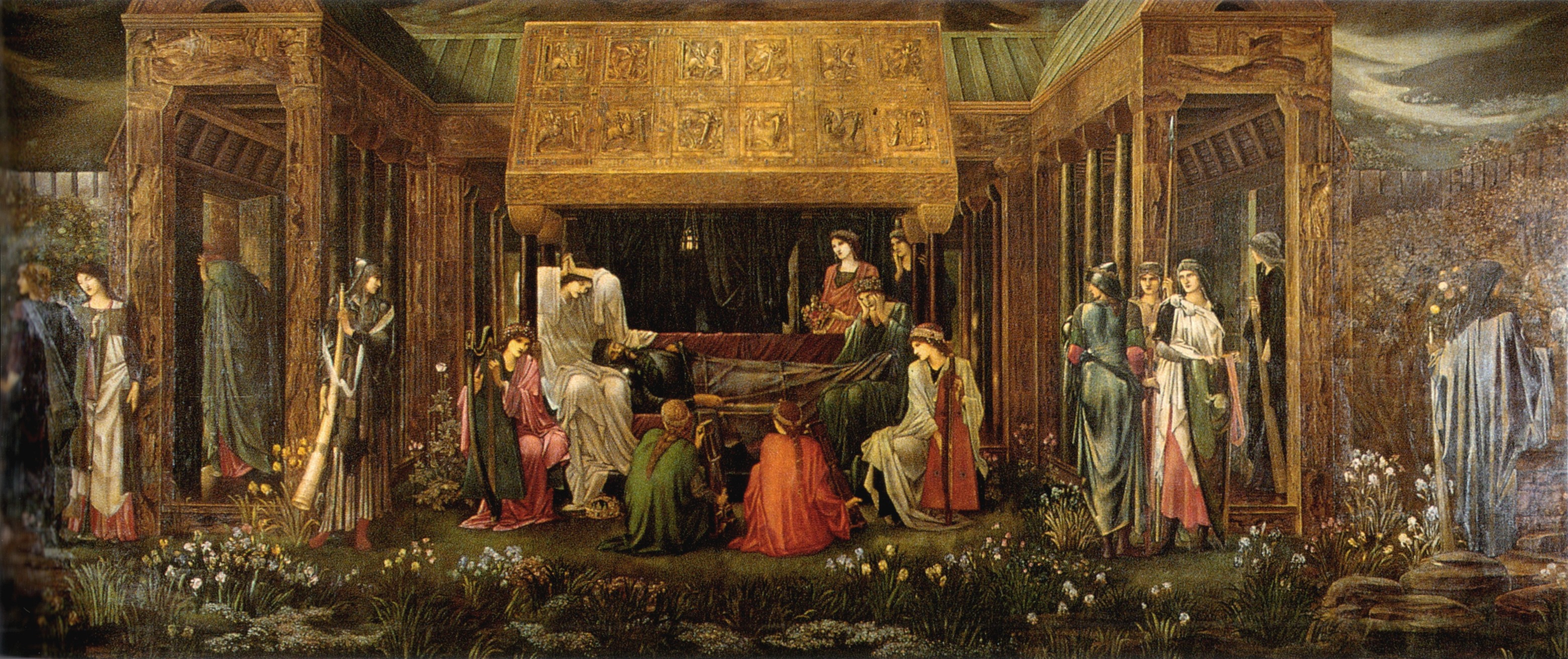

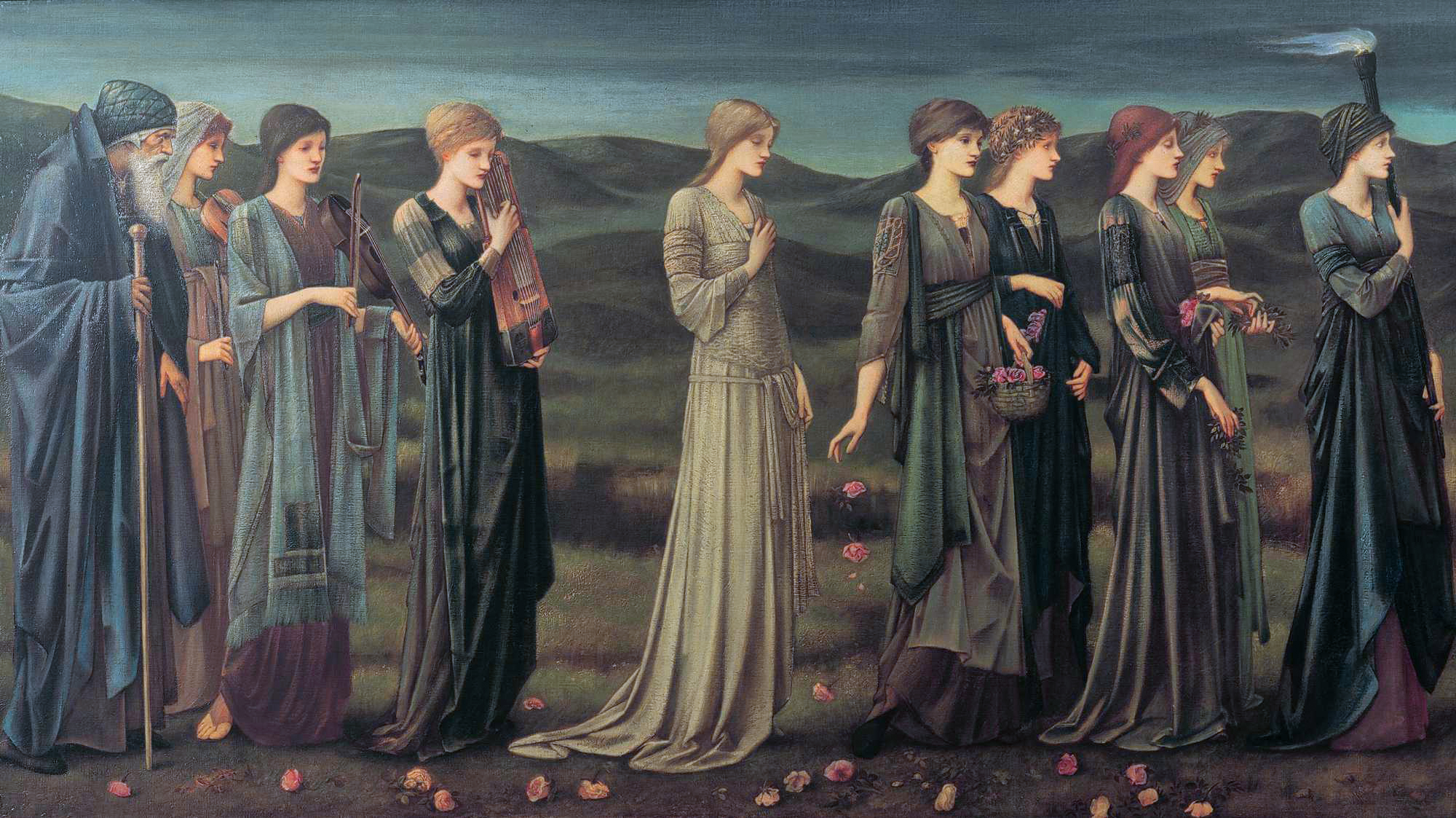

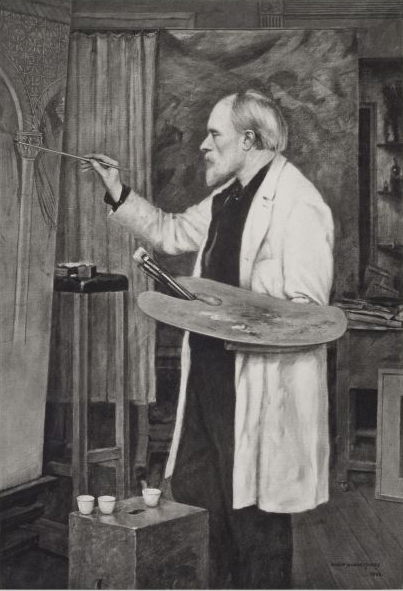

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (16 April 1755 – 30 March 1842), also known as Madame Le Brun, was a French portrait painter in the late 18th century. Her artistic style is generally considered part of the aftermath of Rococo with elements of an adopted Neoclassical style. Her subject matter and color palette can be classified as Rococo, but her style is aligned with the emergence of Neoclassicism. Vigée Le Brun created a name for herself in Ancien Régime society by serving as the portrait painter to Marie Antoinette. She enjoyed the patronage of European aristocrats, actors, and writers, and was elected to art academies in ten cities. Vigée Le Brun created 660 portraits and 200 landscapes. In addition to many works in private collections, her paintings are owned by major museums, such as the Louvre Paris, Uffizi Florence, Hermitage Museum Saint Petersburg, National Gallery in London, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and many other collections in continental Europe and the United States. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, aussi appelée Élisabeth Vigée, Élisabeth Le Brun ou Élisabeth Lebrun, née Louise-Élisabeth Vigée le 16 avril 1755 à Paris, et morte dans la même ville le 30 mars 1842, est une artiste peintre française, considérée comme une grande portraitiste de son temps. Elle a été comparée à Quentin de La Tour ou Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Son art et sa carrière exceptionnelle en font un témoin privilégié des bouleversements de la fin du xviiie siècle, de la Révolution Française et de la Restauration. Fervente royaliste, elle sera successivement peintre de la cour de France, de Marie-Antoinette et de Louis XVI, du Royaume de Naples, de la Cour de l'empereur de Vienne, de l'empereur de Russie et de la Restauration. On lui connaît aussi plusieurs autoportraits, dont deux avec sa fille. BiographyBorn in Paris on 16 April 1755, Élisabeth Louise Vigée was the daughter of Jeanne (1728–1800), a hairdresser from a peasant background, and Louis Vigée, a portraitist, pastellist and member of the Académie de Saint-Luc, from whom she received her first instruction. In 1760, at the age of five, she entered a convent, where she remained until 1766. Her father died when she was 12 years old. In 1768, her mother married a wealthy jeweller, Jacques-François Le Sèvre, and shortly after, the family moved to the Rue Saint-Honoré, close to the Palais Royal. In her memoir, Vigée Le Brun directly stated her feelings about her step-father: "I hated this man; even more so since he made use of my father's personal possessions. He wore his clothes, just as they were, without altering them to fit his figure.” During this period, Élisabeth benefited from the advice of Gabriel François Doyen, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and Joseph Vernet, whose influence is evident in her portrait of her younger brother, playwright and poet Étienne Vigée. By the time she was in her early teens, Élisabeth was painting portraits professionally. After her studio was seized for her practicing without a license, she applied to the Académie de Saint-Luc, which unwittingly exhibited her works in their Salon. In 1774, she was made a member of the Académie. On 11 January 1776, she married Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, a painter and art dealer. Her husband's great-great-uncle was Charles Le Brun, the first director of the French Academy under Louis XIV. Vigée Le Brun began exhibiting her work at their home in Paris, the Hôtel de Lubert, and the Salons she held here supplied her with many new and important contacts. On 12 February 1780, Vigée Le Brun gave birth to a daughter, Jeanne Lucie Louise, whom she called Julie and nicknamed "Brunette". In 1781 she and her husband toured Flanders and the Netherlands, where seeing the works of the Flemish masters inspired her to try new techniques. Her Self-portrait with Straw Hat (1782) was a "free imitation" of Peter Paul Rubens' Le Chapeau de Paille. Dutch and Flemish influences have also been noted in her later paintings The Comte d'Espagnac (1786) and Madame Perregaux (1789). As her career blossomed, Vigée Le Brun was granted patronage by Marie Antoinette. She painted more than 30 portraits of the queen and her family, leading to the common perception that she was the official portraitist of Marie Antoinette. At the Salon of 1783, Vigée Le Brun exhibited Marie-Antoinette in a Muslin Dress (1783), sometimes called Marie-Antoinette en gaulle, in which the queen chose to be shown in a simple, informal white cotton garment. The resulting scandal was prompted by both the informality of the attire and the queen's decision to be shown in that way. On 31 May 1783, Vigée Le Brun was received as a member of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. She was one of only 15 women to be granted full membership in the Académie between 1648 and 1793. Her rival, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, was admitted on the same day. Vigée Le Brun was initially refused on the grounds that her husband was an art dealer, but eventually the Académie was overruled by an order from Louis XVI because Marie Antoinette put considerable pressure on her husband on behalf of her portraitist. As her reception piece, Vigée Le Brun submitted an allegorical painting, Peace Bringing Back Abundance (La Paix ramenant l'Abondance), instead of a portrait. As a consequence, the Académie did not place her work within a standard category of painting—either history or portraiture. Vigée Le Brun's membership in the Académie dissolved after the French Revolution because female academicians were abolished. Vigée Le Brun's later Marie Antoinette and Her Children (1786) was evidently an attempt to improve the queen's image by making her more relatable to the public, in the hopes of countering the bad press and negative judgments that the queen had recently received. The portrait shows the queen at home in the Palace of Versailles, engaged in her official function as the mother of the king's children, but also suggests Marie Antoinette's uneasy identity as a foreign-born queen whose maternal role was her only true function under Salic law. The child, Louis Joseph, on the right is pointing to an empty cradle, which signified her recent loss of a child, further emphasizing Marie Antoinette's role as a mother. In 1787, she caused a minor public scandal when her Self-portrait with Her Daughter Julie (1786) was exhibited at the Salon of 1787 showing her smiling and open-mouthed, which was in direct contravention of traditional painting conventions going back to antiquity. The court gossip-sheet Mémoires secrets commented: "An affectation which artists, art-lovers and persons of taste have been united in condemning, and which finds no precedent among the Ancients, is that in smiling, [Madame Vigée LeBrun] shows her teeth." In light of this and her other Self-portrait with Her Daughter Julie (1789), Simone de Beauvoir dismissed Vigée Le Brun as narcissistic in The Second Sex (1949): "Madame Vigée-Lebrun never wearied of putting her smiling maternity on her canvases.” In October 1789, after the arrest of the royal family during the French Revolution, Vigée Le Brun fled France with her young daughter, Julie. Her husband, who remained in Paris, claimed that Vigée Le Brun went to Italy "to instruct and improve herself", but she certainly feared for her own safety. In her 12-year absence from France, she lived and worked in Italy (1789–1792), Austria (1792–1795), Russia (1795–1801) and Germany (1801). While in Italy, Vigée Le Brun was elected to the Academy in Parma (1789) and the Accademia di San Luca in Rome (1790). In Naples, she painted portraits of Maria Carolina of Austria (sister of Marie Antoinette) and her eldest four living children: Maria Teresa, Francesco, Luisa and Maria Cristina. She later recalled that Luisa "was extremely ugly, and pulled such faces that I was most reluctant to finish her portrait." Vigée Le Brun also painted allegorical portraits of the notorious Emma Hamilton as Ariadne (1790) and as a Bacchante (1792). Lady Hamilton was similarly the model for Vigée Le Brun's Sibyl (1792), which was inspired by the painted sibyls of Domenichino.The painting represents the Cumaean Sibyl, as indicated by the Greek inscription on the figure's scroll, which is taken from Virgil's fourth Eclogue. The Sibyl was Vigée Le Brun's favorite painting. It is mentioned in her memoir more than any other work. She displayed it while in Venice (1792), Vienna (1792), Dresden (1794) and Saint Petersburg (1795); she also sent it to be shown at the Salon of 1798. Like her reception piece, Peace Bringing Back Abundance, Vigée Le Brun regarded her Sibyl as a history painting, the most elevated category in the Académie's hierarchy. While in Vienna, Vigée Le Brun was commissioned to paint Princess Maria Josefa Hermengilde von Esterhazy as Ariadne, and its pendant Princess Karoline von Liechtenstein as Iris Princess Karoline. The portraits depict the Liechtenstein sisters-in-law in unornamented Roman-inspired garments that show the influence of Neoclassicism, and which may have been a reference to the virtuous republican Roman matron Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi. In Russia, where she stayed from 1795 until 1801, she was well-received by the nobility and painted numerous aristocrats, including the former king of Poland, Stanisław August Poniatowski, and members of the family of Catherine the Great. Although the French aesthetic was widely admired in Russia, there remained various cultural differences as to what was deemed acceptable. Catherine was not initially happy with Vigée Le Brun's portrait of her granddaughters, Elena and Alexandra Pavlovna, due to the amount of bare skin the short-sleeved gowns revealed. In order to please the Empress, Vigée Le Brun added sleeves. This tactic seemed effective in pleasing Catherine, as she agreed to sit herself for Vigée Le Brun (although Catherine died of a stroke before this work was due to begin). While in Russia, Vigée Le Brun was made a member of the Academy of Fine Arts of Saint Petersburg. Much to Vigée Le Brun's dismay, her daughter Julie married Gaétan Bernard Nigris, secretary to the Director of the Imperial Theaters of Saint Petersburg. Julie predeceased her mother in 1819. After a sustained campaign by her ex-husband and other family members to have her name removed from the list of counter-revolutionary émigrés, Vigée Le Brun was finally able to return to France in January 1802. She travelled to London in 1803, to Switzerland in 1807, and to Switzerland again in 1808. In Geneva, she was made an honorary member of the Société pour l'Avancement des Beaux-Arts. She stayed at Coppet with Madame de Staël, who appears as the title character in Corinne, ou l'Italie (1807). In her later years, Vigée Le Brun purchased a house in Louveciennes, Île-de-France and divided her time between Louveciennes and Paris. She died in Paris on 30 March 1842, aged 86. She was buried at the Cimetière de Louveciennes near her old home. Her tombstone epitaph says "Ici, enfin, je repose..." (Here, at last, I rest...). Between 1835 and 1837, when Vigée Le Brun was in her 80s, she published her memoirs in three volumes (Souvenirs). During her lifetime, Vigée Le Brun's work was publicly exhibited in Paris at the Académie de Saint-Luc (1774), Salon de la Correspondance (1779, 1781, 1782, 1783) and Salon of the Académie in Paris (1783, 1785, 1787, 1789, 1791, 1798, 1802, 1817, 1824). The first retrospective exhibition of Vigée Le Brun's work was held in 1982 at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. The first major international retrospective exhibition of her art premiered at the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais in Paris (2015—2016) and was subsequently shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (2016) and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa (2016). BiographieÉlisabeth-Louise voit le jour en 1755. Ses parents, Louis Vigée, pastelliste et membre de l’Académie de Saint-Luc et Jeanne Maissin, d’origine paysanne, se marient en 1750; un frère cadet, Étienne Vigée, qui deviendra un auteur dramatique à succès, naît deux ans plus tard. Née rue Coquillière à Paris, Élisabeth est baptisée à l’église Saint-Eustache de Paris, puis mise en nourrice. Dans la bourgeoisie et l'aristocratie, il n'est pas encore dans les habitudes d'élever ses enfants soi-même, aussi l’enfant est-elle confiée à des paysans des environs d’Épernon. Son père vient la rechercher six ans plus tard, la ramène à Paris dans l'appartement familial rue de Cléry. Élisabeth-Louise entre comme pensionnaire à l’école du couvent de la Trinité, rue de Charonne dans le faubourg Saint-Antoine, afin de recevoir la meilleure éducation possible. Dès cet âge, son talent précoce pour le dessin s’exprime : dans ses cahiers, sur les murs de son école. En 1766, Élisabeth-Louise quitte le couvent et vient vivre aux côtés de ses parents. Son père meurt accidentellement d'une septicémie après avoir avalé une arête de poisson, le 9 mai 1767. Élisabeth-Louise, qui n'a que douze ans, mettra longtemps à faire son deuil puis décide de s'adonner à ses passions, la peinture, le dessin et le pastel. Sa mère se remarie dès le 26 décembre 1767 avec un joaillier fortuné mais avare, Jacques-François Le Sèvre (1724-1810) ; les relations d'Élisabeth-Louise avec son beau-père sont difficiles. Le premier professeur d’Élisabeth fut son père, Louis Vigée. Après le décès de ce dernier, c’est un autre peintre, Gabriel-François Doyen, meilleur ami de la famille et célèbre en son temps comme peintre d'histoire, qui l’encourage à persévérer dans le pastel et dans l’huile ; conseil qu’elle suivra. C’est certainement conseillée par Doyen, qu’en 1769 Élisabeth Vigée se rend chez le peintre Gabriel Briard, une connaissance de ce dernier (pour avoir eu le même maître, Carl van Loo). Briard est membre de l’Académie royale de peinture, et donne volontiers des leçons, bien qu'il ne soit pas encore professeur. Peintre médiocre, il a surtout la réputation d’être un bon dessinateur et possède en plus un atelier au palais du Louvre ; Élisabeth fait de rapides progrès et, déjà, commence à faire parler d’elle. C’est au Louvre qu’elle fait la connaissance de Joseph Vernet, artiste célèbre dans toute l’Europe. Il est l'un des peintres les plus courus de Paris, ses conseils font autorité, et il ne manquera pas de lui en prodiguer. « J’ai constamment suivi ses avis ; car je n’ai jamais eu de maître proprement dit », écrit-elle dans ses mémoires. Quoi qu’il en soit, Vernet, qui consacrera de son temps à la formation de « Mlle Vigée », et Jean-Baptiste Greuze la remarquent et la conseillent. Elle peint son premier tableau reconnu en 1770, un portrait de sa mère (Madame Le Sèvre). En 1770, le dauphin Louis-Auguste, futur Louis XVI, petit-fils du roi Louis XV, épouse Marie-Antoinette d'Autriche à Versailles, fille de l'impératrice Marie-Thérèse. À la même époque, la famille Le Sèvre-Vigée s’installe rue Saint-Honoré, face au Palais-Royal, dans l'hôtel de Lubert. Louise-Élisabeth Vigée commence à réaliser des portraits de commande et à peindre de nombreux autoportraits. Lorsque son beau-père se retire des affaires en 1775, la famille s'installe rue de Cléry, dans l'hôtel Lubert, dont le principal locataire est Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Lebrun qui exerce les professions de marchand et restaurateur de tableaux, d'antiquaire et de peintre. Il est un spécialiste de peinture hollandaise dont il a publié des catalogues. Elle visite avec le plus vif intérêt la galerie de tableaux de Lebrun et y parfait ses connaissances picturales. Ce dernier devient son agent, s'occupe de ses affaires. Déjà marié une première fois en Hollande, il la demande en mariage. Libertin et joueur, il a mauvaise réputation, et le mariage est formellement déconseillé à la jeune artiste. Cependant, désireuse d'échapper à sa famille, elle l'épouse le 11 janvier 1776 dans l'intimité. Élisabeth Vigée devient Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. Elle reçoit cette même année sa première commande de la Cour du comte de Provence, le frère du roi puis, le 30 novembre 1776, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun est admise à travailler pour la Cour de Louis XVI. En 1778, elle devient peintre officielle de la reine et est donc appelée pour réaliser le premier portrait de la reine Marie-Antoinette d'après nature. Son hôtel particulier devient un lieu à la mode, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun traverse une période de succès et son mari y ouvre une salle des ventes dans laquelle il vend des antiquités et des tableaux de Greuze, Fragonard, etc. Elle vend ses portraits pour 12 000 francs sur lesquels elle ne touche que 6 francs, son mari empochant le reste, comme elle le dit dans ses Souvenirs : « J'avais sur l'argent une telle insouciance, que je n'en connaissais presque pas la valeur. » Le 12 février 1780, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun donne naissance à sa fille Jeanne-Julie-Louise. Elle continue à peindre pendant les premières contractions et, dit-on, lâche à peine ses pinceaux pendant l’accouchement. Sa fille Julie sera le sujet de nombreux portraits. Une seconde grossesse quelques années plus tard donnera un enfant mort en bas âge. En 1781, elle voyage à Bruxelles avec son mari pour assister et acheter à la vente de la collection du défunt gouverneur Charles-Alexandre de Lorraine ; elle y rencontre le prince de Ligne. Inspirée par Rubens qu'elle admire, elle peint son Autoportrait au chapeau de paille en 1782 (Londres, National Gallery). Alors qu'elle n'arrivait pas à y être admise, elle est reçue à l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture le 31 mai 1783 en même temps que sa concurrente Adélaïde Labille-Guiard et contre la volonté de Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre, premier peintre du roi. Son sexe et la profession de son mari marchand de tableaux sont pourtant de fortes oppositions à son entrée, mais l'intervention protectrice de Marie-Antoinette lui permet d'obtenir ce privilège de Louis XVI. Vigée Le Brun présente une peinture de réception (alors qu’on ne lui en demandait pas), La Paix ramenant l’Abondance réalisée en 1783 (Paris, musée du Louvre), pour être admise en qualité de peintre d’Histoire. Forte de l'appui de la reine, elle se permet l'impertinence d'y montrer un sein découvert, alors que les nus académiques étaient réservés aux hommes. Elle est reçue sans qu’aucune catégorie soit précisée. En septembre de la même année, elle participe au Salon pour la première fois et y présente Marie-Antoinette dit « à la Rose » : initialement, elle a l'audace de présenter la reine dans une robe en gaule, mousseline de coton qui est généralement utilisée en linge de corps ou d'intérieur, mais les critiques se scandalisent du fait que la reine s'est fait peindre en chemise, si bien qu'au bout de quelques jours, Vigée Le Brun doit le retirer et le remplacer par un portrait identique mais avec une robe plus conventionnelle. Dès lors, les prix de ses tableaux s'envolent. Avant 1789, l'œuvre d'Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun est composé de portraits, genre à la mode dans la seconde moitié du xviiie siècle, pour les clients fortunés et aristocratiques qui constituent sa clientèle. Parmi ses portraits de femmes, on peut citer notamment les portraits de Marie-Antoinette (une vingtaine sans compter ceux des enfants) ; Catherine Noël Worlee (la future princesse de Talleyrand) qu’elle réalisa en 1783 et qui fut exposé au Salon de peinture de Paris de cette même année 1783 ; la sœur de Louis XVI, Mme Élisabeth ; l'épouse du comte d'Artois ; deux amies de la reine : la princesse de Lamballe et la comtesse de Polignac. En 1786, elle peint son premier autoportrait avec sa fille et le portrait de Marie-Antoinette et ses enfants. Les deux tableaux sont exposés au Salon de peinture de Paris de la même année et c'est l'autoportrait avec sa fille qui est encensé par le public. En 1788, elle peint ce qu'elle considère comme son chef-d'œuvre : Le Portrait du peintre Hubert Robert. Au sommet de sa gloire, dans son hôtel particulier parisien, rue de Cléry, où elle reçoit une fois par semaine la haute société, elle donne un « souper grec », qui défraye la chronique par l'ostentation qui s'y déploie et pour laquelle on la soupçonne d'avoir dépensé une fortune. Le coût du dîner de 20 000 francs fut rapporté au roi Louis XVI qui s'emporta contre l'artiste. À l’été 1789, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun se trouve à Louveciennes chez la comtesse du Barry, la dernière maîtresse de Louis XV, dont elle a commencé le portrait, lorsque les deux femmes entendent le canon tonner dans Paris. Dans la nuit du 5 au 6 octobre 1789, alors que la famille royale est ramenée de force à Paris, Élisabeth quitte la capitale avec sa fille, Julie, sa gouvernante et cent louis, laissant derrière elle son époux qui l'encourage à fuir, ses peintures et le million de francs qu'elle a gagné à son mari, n'emportant que 20 francs, écrit-elle dans ses Souvenirs. Elle arrive à Rome en novembre 1789. En 1790, elle est reçue à la Galerie des Offices en réalisant son Autoportrait, qui obtient un grand succès. Elle envoie des œuvres à Paris au Salon. L’artiste effectue son Grand Tour et vit entre Florence, Rome où elle retrouve Ménageot, et Naples avec Talleyrand et Lady Hamilton, puis Vivant Denon, le premier directeur du Louvre, à Venise. Elle veut rentrer en France, mais elle est inscrite, en 1792, sur la liste des émigrés et perd ainsi ses droits civiques. Elle se rend à Vienne en Autriche, d'où elle ne pense pas partir et où, en tant qu'ancienne peintre de la reine Marie-Antoinette, elle bénéficie de la protection de la famille impériale. À Paris, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Lebrun a vendu tout son fonds de commerce en 1791 pour éviter la faillite, alors que le marché de l'art s'est effondré et a perdu la moitié de sa valeur. Proche de Jacques-Louis David, il demande en 1793, sans succès, que le nom de sa femme soit retiré de la liste des émigrés. Invoquant la désertion de sa femme, Jean-Baptiste-Pierre demande et obtient le divorce en 1794 pour se protéger et préserver leurs biens. Quant à Elisabeth-Louise, elle parcourt l'Europe en triomphe. En 1809, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun revient en France et s'installe à Louveciennes, dans une maison de campagne voisine du château ayant appartenu à la comtesse du Barry (guillotinée en 1793) dont elle avait peint trois portraits avant la Révolution. Elle vit alors entre Louveciennes et Paris. À Louveciennes, où elle vit huit mois de l'année, le reste en hiver à Paris, où elle tient salon et croise les artistes en renom le dimanche. Son mari, dont elle avait divorcé, meurt en 1813. En 1814, elle se réjouit du retour de Louis XVIII, « Le monarque qui convenait à l'époque », écrit-elle dans ses mémoires. Après 1815 et la Restauration, ses tableaux, en particulier les portraits de Marie-Antoinette, sont restaurés et ré-accrochés au Louvre, à Fontainebleau et à Versailles. Sa fille finit sa vie dans la misère en 1819, et son frère, Étienne Vigée, meurt en 1820. Elle effectue un dernier voyage à Bordeaux au cours duquel elle effectue de nombreux dessins de ruines. En 1835, elle publie ses Souvenirs avec l'aide de ses nièces Caroline Rivière, venue vivre avec elle, et d'Eugénie Tripier Le Franc, peintre portraitiste et dernière élève. C'est cette dernière qui écrit de sa main une partie des souvenirs du peintre, d'où les doutes émis par certains historiens quant à leur authenticité. À la fin de sa vie, l'artiste en proie à des attaques cérébrales, perd la vue. Elle meurt à Paris à son domicile de la rue Saint-Lazare le 30 mars 1842 et est enterrée au cimetière paroissial de Louveciennes. Sur la pierre tombale, privée de sa grille d'entourage, se dresse la stèle de marbre blanc portant l'épitaphe « Ici, enfin, je repose… », ornée d'un médaillon représentant une palette sur un socle et surmontée d'une croix. Sa tombe a été transférée en 1880 au cimetière des Arches de Louveciennes, lorsque l'ancien cimetière a été désaffecté. À l'invitation de l'ambassadeur de Russie, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun se rend en Russie, pays qu'elle considèrera comme sa seconde patrie. En 1799, une pétition de deux cent cinquante-cinq artistes, littérateurs et scientifiques demandent au Directoire le retrait de son nom de la liste des émigrés. En 1800, son retour est précipité par le décès de sa mère à Neuilly et le mariage, qu'elle n'approuve pas, de sa fille Julie avec Gaëtan Bertrand Nigris, directeur des Théâtres impériaux à Saint-Pétersbourg. C'est pour elle un déchirement. Déçue par son mari, elle avait fondé tout son univers affectif sur sa fille. Les deux femmes ne se réconcilieront jamais totalement. Elle est accueillie à Paris le 18 janvier 1802, où elle retrouve son mari, avec qui elle revit sous le même toit. Si le retour d’Élisabeth est salué par la presse, elle a du mal à retrouver sa place dans la nouvelle société née de la Révolution et de l'Empire. Quelques mois plus tard, elle quitte la France pour l'Angleterre, où elle s'installe à Londres pour trois ans. Là, elle rencontre Lord Byron, le peintre Benjamin West, retrouve Lady Hamilton, la maîtresse de l'amiral Nelson qu'elle avait connue à Naples, et admire la peinture de Joshua Reynolds. Elle vit avec la Cour de Louis XVIII et du comte d'Artois en exil entre Londres, Bath et Douvres. En 1805, elle reçoit la commande du portrait de Caroline Murat, épouse du général Murat, une des sœurs de Napoléon devenue reine de Naples, et cela se passe mal : « J’ai peint de véritables princesses qui ne m’ont jamais tourmentée et ne m’ont pas fait attendre », dira l'artiste quinquagénaire à cette jeune reine parvenue. Le 14 janvier 1807, elle rachète à son mari endetté son hôtel particulier parisien et sa salle des ventes. Mais en butte au pouvoir impérial, Vigée Le Brun quitte la France pour la Suisse, où elle rencontre Madame de Staël en 1807. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun fut célèbre de son vivant, mais son œuvre associée à l'Ancien Regime, et en particulier à la Reine Marie-Antoinette va être sous-estimée jusqu'au xxie siècle. La première rétrospective de son œuvre en France a lieu de septembre 2015 au 11 janvier 2016 au Grand Palais de Paris. Accompagnée de films, de documentaires, la peintre de Marie-Antoinette apparaît alors dans toute sa complexité. ArticlesVideosÉlisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842) : Une vie, une œuvre (2015 / France Culture) The Remarkable Talent Of Elizabeth Vigée Lebrun | Portraits of Marie Antoinette Pt. 1 | Perspective The Prolonged Exile Of France’s Finest Artist | Portraits of Marie Antoinette Part 2 | Perspective Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet, ARA (28 August, 1833 – 17 June, 1898) was a British artist and designer associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, who worked with William Morris on decorative arts as a founding partner in Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. Burne-Jones was involved in the rejuvenation of the tradition of stained glass art in Britain; his works include windows in numerous Cathedrals and churches in England. Burne-Jones's early paintings show the inspiration of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, but by the 1860s Burne-Jones was discovering his own artistic "voice". In 1877, he was persuaded to show eight oil paintings at the Grosvenor Gallery (a new rival to the Royal Academy). These included The Beguiling of Merlin. The timing was right and he was taken up as a herald and star of the new Aesthetic Movement. Burne-Jones worked in crafts; including designing ceramic tiles, jewellery, tapestries, and mosaics. BiographyEdward Coley Burne Jones (the hyphen came later) was born in Birmingham, the son of a Welshman, Edward Richard Jones, a frame-maker at Bennetts Hill(A blue plaque commemorates the painter's childhood). His mother Elizabeth Jones (née Coley) died within six days of his birth, and Edward was raised by his father, and the family housekeeper, Ann Sampson, an obsessively affectionate but humourless, and unintellectual local girl. He attended Birmingham's King Edward VI grammar school in 1844 and the Birmingham School of Art from 1848 to 1852, before studying theology at Exeter College, Oxford. At Oxford, he became a friend of William Morris as a consequence of a mutual interest in poetry. The two Exeter undergraduates, together with a group of Jones' friends from Birmingham known as the Birmingham Set, formed a society, which they called "The Brotherhood". The members of the brotherhood read John Ruskin and Alfred Tennyson, visited churches, and worshipped the Middle Ages. At this time, Burne-Jones discovered Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur which would be very influential in his life. At that time, neither Burne-Jones nor Morris knew Dante Gabriel Rossetti personally, but both were much influenced by his works, and met him by recruiting him as a contributor to their Oxford and Cambridge Magazine which Morris founded in 1856 to promote their ideas. Burne-Jones had intended to become a church minister, but under Rossetti's influence both he and Morris decided to become artists, and Burne-Jones left college before taking a degree to pursue a career in art. Burne-Jones once admitted that after leaving Oxford he "found himself at five-and-twenty what he ought to have been at fifteen". He had had no regular training as a draughtsman, and lacked the confidence of science. But his extraordinary faculty of invention as a designer was already ripening; his mind, rich in knowledge of classical story and medieval romance, teemed with pictorial subjects, and he set himself to complete his set of skills by resolute labour, witnessed by his drawings. Edward Burne-Jones works of this first period are all more or less tinged by the influence of Dante Rossetti; but they are already differentiated from the elder master's style by their more facile though less intensely felt elaboration of imaginative detail. Many are pen-and-ink drawings on vellum, exquisitely finished, of which his Waxen Image (1856) is one of the earliest and best examples. Although the subject, medium and manner derive from Rossetti's inspiration, it is not the hand of a pupil merely, but of a potential master. This was recognised by Rossetti himself, who before long avowed that he had nothing more to teach him. In February 1857, Rossetti wrote to William Bell Scott: Two young men, projectors of the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, have recently come up to town from Oxford, and are now very intimate friends of mine. Their names are Morris and Jones. They have turned artists instead of taking up any other career to which the university generally leads, and both are men of real genius. Jones's designs are marvels of finish and imaginative detail, unequalled by anything unless perhaps Albert Dürer's finest works. In 1856 Burne-Jones became engaged to Georgiana "Georgie" MacDonald (1840–1920), one of the MacDonald sisters. She was training to be a painter, and was the sister of Burne-Jones's old school friend. Burne-Jones's first sketch in oils dates from this same year, 1856, and during 1857 he made for Bradfield College the first of what was to be an immense series of cartoons for stained glass. In the autumn of 1857 Burne-Jones joined Morris, Valentine Prinsep, J. R. Spencer Stanhope and others in Rossetti's ill-fated scheme to decorate the walls of the Oxford Union. None of the painters had mastered the technique of fresco, and their pictures had begun to peel from the walls before they were completed. In 1858 he decorated a cabinet with the Prioress's Tale from Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, his first direct illustration of the work of a poet whom he especially loved and who inspired him with endless subjects. In 1859 Burne-Jones made his first journey to Italy. He saw Florence, Pisa, Siena, Venice and other places, and appears to have found the gentle and romantic Sienese more attractive than any other school. Rossetti's influence persisted, and is visible, more strongly perhaps than ever before, in the two watercolours of 1860, Sidonia von Bork and Clara von Bork. Both paintings illustrate the 1849 gothic novel Sidonia the Sorceress by Lady Wilde, a translation of Sidonia Von Bork: Die Klosterhexe (1847) by Johann Wilhelm Meinhold. In 1860, Burne-Jones married Georgiana MacDonald, after which she made her own work in woodcuts, and became a close friend of George Eliot. (Another MacDonald sister was the mother of Rudyard Kipling, who was thus Burne-Jones's nephews by marriage). Georgiana gave birth to a son, Philip, in 1861. That same year, William Morris founded the decorative arts firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. with Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Ford Madox Brown and Philip Webb as partners, together with Charles Faulkner and Peter Paul Marshall, the former of whom was a member of the Oxford Brotherhood, and the latter a friend of Brown and Rossetti. The prospectus set forth that the firm would undertake carving, stained glass, metal-work, paper-hangings, chintzes (printed fabrics), and carpets. Since then, Burne-Jones was responsible for designs of stained glass windows and panel figures in various Cathedrals and churches, and later tapestries until the end of his career. In 1864, Burne-Jones was elected an associate of the Society of Painters in Water-Colours—which is known as the Old Water-Colour Society—and exhibited, among other works, The Merciful Knight, the first picture which fully revealed his ripened personality as an artist. In the winter of that year, Georgiana became gravely ill with scarlet fever and gave birth to a second son who died soon thereafter. The family then moved to 41 Kensington Square. In 1866, Edward Burne-Jones's daughter Margaret was born, that same year, Mrs. Cassavetti commissioned Burne-Jones to paint her daughter, Maria Zambaco, in Cupid finding Psyche, an introduction which led to their tragic affair. In 1867 Burne-Jones and his family settled at the Grange, an 18th-century house set in a garden in North End, Fulham, London. In 1870, Burne-Jones resigned his membership following a controversy over his painting Phyllis and Demophoön. The features of Maria Zambaco were clearly recognisable in the barely draped Phyllis, and the undraped nakedness of Demophoön coupled with the suggestion of female sexual assertiveness offended Victorian sensibilities. Burne-Jones was asked to make a slight alteration, but instead "withdrew not only the picture from the walls, but himself from the Society." During the next seven years, 1870–1877, only two works of the painter's were exhibited. This was partly due to a number of bitterly hostile attacks in the press, and partly due to his passionate affair with his Greek model Maria Zambaco, which ended with her trying to commit suicide by throwing herself in Regent's Canal. Both exhibited works were water-colours, shown at the Dudley Gallery in 1873, one of them being the beautiful Love Among the Ruins, destroyed twenty years later by a cleaner who supposed it to be an oil painting, but afterwards reproduced in oils by the painter. He thus began painting in oils again, working at them in turn, and having them on hand. The first Briar Rose series, Laus Veneris, The Golden Stairs, The Pygmalion series, and The Mirror of Venus are among the works planned and completed, or carried far towards completion. During these difficult years Edward Burne-Jones's Georgiana developed a friendship with William Morris, whose wife Jane Morris had fallen in love with Dante Rossetti. William Morris and Georgie Burne Jones may have been in love, but if he asked her to leave her husband, she refused. In the end, the Burne-Joneses remained together, as did the Morrises, but Morris and Georgiana were close for the rest of their lives. The beginnings of Burne-Jones' partnership with the fine-art photographer Frederick Hollyer, whose reproductions of paintings and—especially—drawings would expose an audience to Burne-Jones's works in the coming decades, began during this period. At last, in May 1877, the day of recognition came with the opening of the first exhibition of the Grosvenor Gallery, when the Days of Creation, The Beguiling of Merlin, and the Mirror of Venus were all shown. Burne-Jones followed up the signal success of these pictures with Laus Veneris, the Chant d'Amour, Pan and Psyche, and other works, exhibited in 1878. Most of these pictures are painted in brilliant colours. A change is noticeable in 1879 in the Annunciation and in the four pictures making up the second series of Pygmalion and the Image; the former of these, one of the simplest and most perfect of the artist's works, is subdued and sober; in the latter a scheme of soft and delicate tints was attempted, not with entire success. A similar temperance of colours marks The Golden Stairs, first exhibited in 1880. That same year, the Burne-Joneses bought Prospect House in Rottingdean, near Brighton in Sussex, as their holiday home and soon after, the next door Aubrey Cottage to create North End House, reflecting the fact that their Fulham home was in North End Road. (Years later, in 1923, Sir Roderick Jones, head of Reuters, and his wife, playwright and novelist Enid Bagnold, were to add the adjacent Gothic House to the property, which became the inspiration and setting for her play The Chalk Garden). In 1883, Burne-Jones exhibited his almost sombre Wheel of Fortune, which was followed in 1884 by King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid, in which Burne-Jones once more indulged his love of gorgeous colour, refined by the period of self-restraint. He next turned to two important sets of pictures, The Briar Rose and The Story of Perseus, although these were not completed. Burne-Jones's paintings were one strand in the evolving tapestry of Aestheticism from the 1860s through the 1880s, which considered that art should be valued as an object of beauty engendering a sensual response, rather than for the story or moral implicit in the subject matter. In many ways this was antithetical to the ideals of Ruskin and the early Pre-Raphaelites. Edward Burne-Jones was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1885, and the following year he exhibited uniquely at the Academy, showing The Depths of the Sea, a painting of a mermaid carrying down with her a youth whom she has unconsciously drowned in the impetuosity of her love. This picture adds to the habitual haunting charm a tragic irony of conception and a felicity of execution which give it a place apart among Burne-Jones's works. He formally resigned his Associateship in 1893. One of the Perseus series was exhibited in 1887 and two more in 1888, with The Brazen Tower, inspired by the same legend. In 1890 the second series of The Legend of Briar Rose were exhibited by themselves and won admiration. The huge watercolour, The Star of Bethlehem, painted for the corporation of Birmingham, was exhibited in 1891. A long illness for a time checked the painter's activity, which, when resumed, was much occupied with decorative schemes. An exhibition of his work was held at the New Gallery in the winter of 1892–1893. To this period belong his comparatively few portraits. In 1894, Burne-Jones was made a baronet, and he legally changed his name to Burne-Jones at that time, hyphenating his name, merely—as he wrote later—to avoid "annihilation" in the mass of Joneses. Ill-health again interrupted the progress of his works, chief among which was the vast Arthur in Avalon. Although known primarily as a painter, Burne-Jones was active as an illustrator, helping the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic to enter mainstream awareness. He designed books for the Kelmscott Press between 1892 and 1898. His illustrations appeared in the following books, among others:

William Morris died in 1896, which devastated Burne-Jones and his health declined substantially. In 1898 he suffered an attack of influenza, and had apparently recovered when he was again taken suddenly ill, and died on 17 June 1898. Six days later, at the intervention of the Prince of Wales, a memorial service was held at Westminster Abbey. It was the first time an artist had been so honoured. Burne-Jones' ashes were buried in the churchyard at St Margaret's Church, Rottingdean, a place he knew through summer family holidays. In the winter following his death, a second exhibition of his works was held at the New Gallery, and an exhibition of his drawings (including some of the charmingly humorous sketches made for children) at the Burlington Fine Arts Club. His troubled son Philip, who became a successful portrait painter, died in 1926. His adored daughter Margaret (died 1953) married John William Mackail (1850–1945), the friend and biographer of William Morris, and Professor of Poetry at Oxford from 1911 to 1916. Their children were the novelists Angela Thirkell and Denis Mackail, and the youngest, Clare Mackail.

|

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|