|

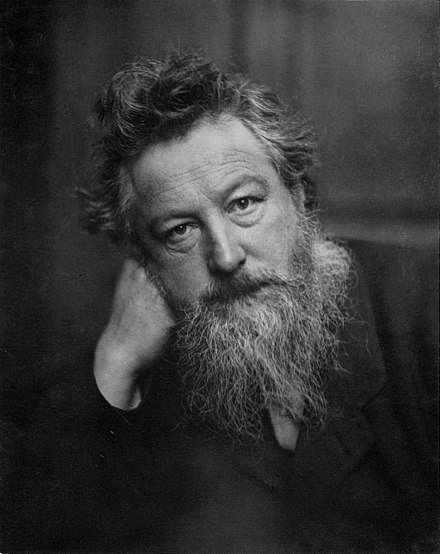

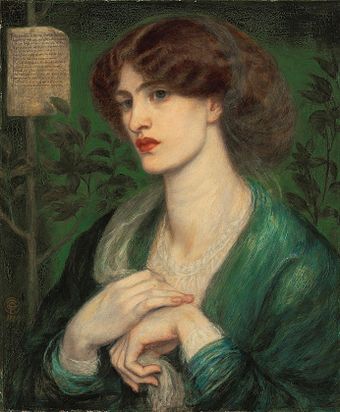

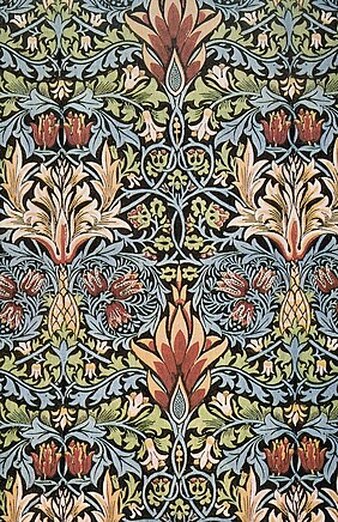

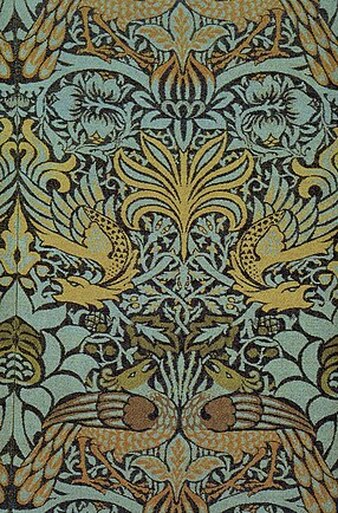

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditional British textile arts and methods of production. His literary contributions helped to establish the modern fantasy genre, while he helped win acceptance of socialism in fin de siècle Great Britain. Morris was born in Walthamstow, Essex, to a wealthy middle-class family. He came under the strong influence of medievalism while studying Classics at Oxford University, there joining the Birmingham Set. After university, he married Jane Burden, and developed close friendships with Pre-Raphaelite artists Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti and with Neo-Gothic architect Philip Webb. Webb and Morris designed Red House in Kent where Morris lived from 1859 to 1865, before moving to Bloomsbury, central London. In 1861, Morris founded the Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. decorative arts firm with Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Webb, and others, which became highly fashionable and much in demand. The firm profoundly influenced interior decoration throughout the Victorian period, with Morris designing tapestries, wallpaper, fabrics, furniture, and stained glass windows. In 1875, he assumed total control of the company, which was renamed Morris & Co. Morris rented the rural retreat of Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire, from 1871 while also retaining a main home in London. He was greatly influenced by visits to Iceland with Eiríkr Magnússon, and he produced a series of English-language translations of Icelandic Sagas. He also achieved success with the publication of his epic poems and novels, namely The Earthly Paradise (1868–1870), A Dream of John Ball (1888), the Utopian News from Nowhere (1890), and the fantasy romance The Well at the World's End (1896). In 1877, he founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings to campaign against the damage caused by architectural restoration. He embraced Marxism and was influenced by anarchism in the 1880s and became a committed revolutionary socialist activist. He founded the Socialist League in 1884 after an involvement in the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), but he broke with that organisation in 1890. In 1891, he founded the Kelmscott Press to publish limited-edition, illuminated-style print books, a cause to which he devoted his final years. Morris is recognised as one of the most significant cultural figures of Victorian Britain. He was best known in his lifetime as a poet, although he posthumously became better known for his designs. The William Morris Society founded in 1955 is devoted to his legacy, while multiple biographies and studies of his work have been published. Many of the buildings associated with his life are open to visitors, much of his work can be found in art galleries and museums, and his designs are still in production. BiographyWilliam Morris was born at Elm House in Walthamstow, Essex, on 24 March 1834. Raised into a wealthy middle-class family, he was named after his father, a financier who worked as a partner in the Sanderson & Co. firm, bill brokers in the City of London. His mother was Emma Morris who descended from a wealthy bourgeois family. Morris was the third of his parents' surviving 9 children. The Morris family were followers of the evangelical Protestant form of Christianity, and William was baptised four months after his birth at St. Mary's Church, Walthamstow. As a child, Morris was kept largely housebound at Elm House by his mother; there, he spent much time reading, favouring the novels of Walter Scott. Aged 6, Morris moved with his family to the Georgian Italianate mansion at Woodford Hall, Woodford, Essex, which was surrounded by 50 acres of land adjacent to Epping Forest. He took an interest in fishing with his brothers as well as gardening in the Hall's grounds, and spent much time exploring the Forest. He also took rides through the Essex countryside on his pony, and visited the various churches and cathedrals throughout the country, marveling at their architecture. His father also took him on visits outside of the county. Aged 9, he was then sent to Misses Arundale's Academy for Young Gentlemen, a nearby preparatory school; although initially riding there by pony each day, he later began boarding, intensely disliking the experience. In 1847, Morris's father died unexpectedly. From this point, the family relied upon continued income from the copper mines at Devon Great Consols, and sold Woodford Hall to move into the smaller Water House. In February 1848 Morris began his studies at Marlborough College in Marlborough, Wiltshire, where he gained a reputation as an eccentric nicknamed "Crab". He despised his time there, being bullied, bored, and homesick. He did use the opportunity to visit many of the prehistoric sites of Wiltshire. The school was Anglican in faith and in March 1849 Morris was confirmed by the Bishop of Salisbury in the college chapel, developing an enthusiastic attraction towards the Anglo-Catholic movement and its Romanticist aesthetic. At Christmas 1851, Morris was removed from the school and returned to Water House, where he was privately tutored. In June 1852 Morris entered Exeter College at Oxford University. He disliked the college and was bored by the manner in which they taught him Classics. Instead he developed a keen interest in Medieval history and Medieval architecture, inspired by the many Medieval buildings in Oxford. This interest was tied to Britain's growing Medievalist movement, a form of Romanticism that rejected many of the values of Victorian industrial capitalism. For Morris, the Middle Ages represented an era with strong chivalric values and an organic, pre-capitalist sense of community, both of which he deemed preferable to his own period. This attitude was compounded by his reading of Thomas Carlyle's book Past and Present (1843), in which Carlyle championed Medieval values as a corrective to the problems of Victorian society. Under this influence, Morris's dislike of contemporary capitalism grew. At the college, Morris met fellow first-year undergraduate Edward Burne-Jones, who became his lifelong friend and collaborator. Although from very different backgrounds, they found that they had a shared attitude to life, both being keenly interested in Anglo-Catholicism and Arthurianism. Through Burne-Jones, Morris joined a group of undergraduates from Birmingham who were studying at Pembroke College: William Fulford, Richard Watson Dixon, Charles Faulkner, and Cormell Price. They were known among themselves as the "Brotherhood" and to historians as the Birmingham Set. Morris was the most affluent member of the Set, and was generous with his wealth toward the others. Like Morris, the Set were fans of the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and would meet together to recite the plays of William Shakespeare. William Morris was heavily influenced by the writings of the art critic John Ruskin, being particularly inspired by his chapter "On the Nature of Gothic Architecture" in the second volume of The Stones of Venice; he later described it as "one of the very few necessary and inevitable utterances of the century". Morris adopted Ruskin's philosophy of rejecting the tawdry industrial manufacture of decorative arts and architecture in favour of a return to hand-craftsmanship, raising artisans to the status of artists, creating art that should be affordable and hand-made, with no hierarchy of artistic mediums. Ruskin had achieved attention in Victorian society for championing the art of a group of painters who had emerged in London in 1848 calling themselves the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The Pre-Raphaelite style was heavily Medievalist and Romanticist, emphasising abundant detail, intense colours and complex compositions; it greatly impressed Morris and the Set. Influenced both by Ruskin and by John Keats, Morris began to spend more time writing poetry, in a style that was imitative of much of theirs. Both he and Burne-Jones were influenced by the Romanticist milieu and the Anglo-Catholic movement, and decided to become clergymen in order to found a monastery where they could live a life of chastity and dedication to artistic pursuit, akin to that of the contemporary Nazarene movement. However, as time went on Morris became increasingly critical of Anglican doctrine and the idea faded. In summer 1854, Morris travelled to Belgium to look at Medieval paintings, and in July 1855 went with Burne-Jones and Fulford across northern France, visiting Medieval churches and cathedrals. It was on this trip that he and Burne-Jones committed themselves to "a life of art". For Morris, this decision resulted in a strained relationship with his family, who believed that he should have entered either commerce or the clergy. On a subsequent visit to Birmingham, Morris discovered Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, which became a core Arthurian text for him and Burne-Jones. In January 1856, the Set began publication of The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, designed to contain "mainly Tales, Poetry, friendly critiques and social articles". Mainly funded by Morris, who briefly served as editor and heavily contributed to it with his own stories, poems, reviews and articles, the magazine lasted for twelve issues, and garnered praise from Tennyson and Ruskin. Having passed his finals and been awarded a BA, Morris began an apprenticeship with the Oxford-based Neo-Gothic architect George Edmund Street in January 1856. His apprenticeship focused on architectural drawing, and there he was placed under the supervision of the young architect Philip Webb, who became a close friend. In August 1856 he moved into a flat in Bloomsbury in Central London with Burne-Jones, an area perhaps chosen for its avant-garde associations. Morris was fascinated by London but dismayed at its pollution and rapid expansion into neighbouring countryside, describing it as "the spreading sore". Morris became increasingly fascinated with the idyllic Medievalist depictions of rural life which appeared in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, and spent large sums of money purchasing such artworks. Burne-Jones shared this interest, but took it further by becoming an apprentice to one of the foremost Pre-Raphaelite painters, Dante Gabriel Rossetti; the three soon became close friends. Through Rossetti, Morris came to associate with poet Robert Browning, and the artists Arthur Hughes, Thomas Woolner, and Ford Madox Brown. Tired of architecture, Morris abandoned his apprenticeship, with Rossetti persuading him to take up painting instead, which he chose to do in the Pre-Raphaelite style. Morris aided Rossetti and Burne-Jones in painting the Arthurian murals at the Oxford Union, although his contributions were widely deemed inferior and unskilled compared to those of the others. At Rossetti's recommendation, Morris and Burne-Jones moved in together to the flat at Bloomsbury's No. 17 Red Lion Square by November 1856. Morris designed and commissioned furniture for the flat in a Medieval style, much of which he painted with Arthurian scenes in a direct rejection of mainstream artistic tastes. Morris also continued writing poetry and began designing illuminated manuscripts and embroidered hangings. In March 1857 Bell and Dandy published a book of Morris's poems, The Defence of Guenevere, which was largely self-funded by the author. It did not sell well and garnered few reviews, most of which were unsympathetic. Disconcerted, Morris would not publish again for a further eight years. In October 1857 Morris met Jane Burden, a woman from a poor working-class background, at a theatre performance. Rosetti initially asked her to model for him. Controversially both Rosetti and Morris were smitten with her; Morris, however, began a relationship with her and they were engaged in spring 1858 and were married in a low-key ceremony held at St Michael at the North Gate church in Oxford on 26 April 1859, before honeymooning in Bruges, Belgium, and settling temporarily at 41 Great Ormond Street, London. Their first daughter was Jane"Jenny" was born in January 1861, and second daughter Mary "May" Morris in March 1862, Morris was a caring father to his daughters, and years later they both recounted having idyllic childhoods. However, there were problems in Morris's marriage as Janey became increasingly close to Rossetti, who often painted her. Jane Burden would later admit that she never loved Morris. In April 1861, Morris founded a decorative arts company, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., with six other partners: Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Webb, Ford Madox Brown, Charles Faulkner, and Peter Paul Marshall. Operating from premises at No. 6 Red Lion Square, they referred to themselves as "the Firm" and were intent on adopting Ruskin's ideas of reforming British attitudes to production. They hoped to reinstate decoration as one of the fine arts and adopted an ethos of affordability and anti-elitism. Although working within the Neo-Gothic school of design, they sought to return completely to Medieval Gothic methods of craftmanship. The products created by the Firm included furniture, architectural carving, metalwork, stained glass windows, and murals. Their stained glass windows proved a particular success in the firm's early years as they were in high demand for the surge in the Neo-Gothic construction and refurbishment of churches. Morris was slowly abandoning painting, recognising that his work lacked a sense of movement; none of his paintings are dated later than 1862. Instead he focused his energies on designing wallpaper patterns, the first being "Trellis", designed in 1862. Morris desired a new home for himself and his daughters resulting in the construction of the Red House in the Kentish hamlet of Upton near Bexleyheath, ten miles from central London. The building's design was a co-operative effort, with Morris focusing on the interiors and the exterior being designed by Webb, for whom the House represented his first commission as an independent architect. Named after the red bricks and red tiles from which it was constructed, Red House rejected architectural norms by being L-shaped. Influenced by various forms of contemporary Neo-Gothic architecture, the House was nevertheless unique, with Morris describing it as "very mediaeval in spirit". Situated within an orchard, the house and garden were intricately linked in their design. It took a year to construct, and cost Morris £4000 at a time when his fortune was greatly reduced by a dramatic fall in the price of his shares. Burne-Jones described it as "the beautifullest place on Earth." After construction, Morris invited friends to visit, most notably Burne-Jones and his wife Georgiana, as well as Rossetti and his wife Lizzie Siddal. They aided him in painting murals on the furniture, walls, and ceilings, much of it based on Arthurian tales, the Trojan War, and Geoffrey Chaucer's stories, while he also designed floral embroideries for the rooms. They also spent much time playing tricks on each other, enjoying games like hide and seek, and singing while accompanied by the piano. Imagining the creation of an artistic community at Upton, Morris helped develop plans for a second house to be constructed adjacent to Red House in which Burne-Jones could live with his family; the plans were abandoned when Burne-Jones' son Christopher died from scarlet fever. By 1864, Morris had become increasingly tired of life at Red House, being particularly unhappy with the 3 to 4 hours spent commuting to his London workplace on a daily basis. He sold Red House, and in autumn 1865 moved with his family to No. 26 Queen Square in Bloomsbury, the same building to which the Firm had moved its base of operations earlier in the summer. At Queen Square, the Morris family lived in a flat directly above the Firm's shop. The Firm's work received increasing interest from people in the United States, resulting in Morris's acquaintance with Henry James and Charles Eliot Norton. However, despite its success, the Firm was not turning over a large net profit, and this, coupled with the decreasing value of Morris' stocks, meant that he had to decrease his spending. short, burly, corpulent, very careless and unfinished in his dress ... He has a loud voice and a nervous restless manner and a perfectly unaffected and businesslike address. His talk indeed is wonderfully to the point and remarkable for clear good sense." Jane's relationship with Rossetti had continued, and by the late 1860s gossip regarding their affair had spread about London, where they were regularly seen spending time together. Morris had continued to devote much time to writing poetry. In 1867 Bell and Dandy published Morris's epic poem, The Life and Death of Jason, at his own expense. The book was a retelling of the ancient Greek myth of the hero Jason and his quest to find the Golden Fleece. In contrast to Morris's former publication, The Life and Death of Jason was well received, resulting in the publishers paying Morris a fee for the second edition. From 1865 to 1870, Morris worked on another epic poem, The Earthly Paradise. Designed as a homage to Chaucer, it consisted of 24 stories, adopted from an array of different cultures, and each by a different narrator; set in the late 14th century, the synopsis revolved around a group of Norsemen who flee the Black Death by sailing away from Europe, on the way discovering an island where the inhabitants continue to venerate the ancient Greek gods. Published in four parts by F. S. Ellis, it soon gained a cult following and established Morris' reputation as a major poet. By 1870, Morris had become a public figure in Britain, resulting in repeated press requests for photographs, which he despised. Morris was keenly interested in Icelandic literature, having befriended the Icelandic theologian Eiríkur Magnússon. Together they produced prose translations of the Eddas and Sagas for publication in English. Morris also developed a keen interest in creating handwritten illuminated manuscripts, producing 18 such books between 1870 and 1875, the first of which was A Book of Verse, completed as a birthday present for Georgina Burne-Jones. Morris deemed calligraphy to be an art form, and taught himself both Roman and italic script, as well as learning how to produce gilded letters. By 1871, he had begun work on a novel set in the present, The Novel on Blue Paper, which was about a love triangle; it would remain unfinished and Morris later asserted that it was not well written. By early summer 1871, Morris began to search for a house outside London where his children could spend time away from the city's pollution. He settled on Kelmscott Manor in the village of Kelmscott, Oxfordshire, obtaining a joint tenancy on the building with Rossetti in June. Morris adored the building, which was constructed circa 1570, and would spend much time in the local countryside. Morris divided his time between London and Kelmscott, however when Rossetti was there he would not spend more than three days at a time at the latter. He became fed up with his family home in Queen Square, and relocated his family to Horrington House in Turnham Green Road, West London, in January 1873. In July 1874 Rossetti left Kelmscott, as a result of the deteriorating friendship between him and Morris. In March 1875, Morris paid £1000 each in compensation to the Firm's partners Rossetti, Brown, and Marshall, although the other partners waived their claims to financial compensation, and The Firm was replaced by Morris & Co. Morris took an increased interest in the process of textile dyeing as a necessary adjunct of his manufacturing business and entered into a co-operative agreement with Thomas Wardle, a silk dyer who operated the Hencroft Works in Staffordshire. As a result, Morris would spend time with Wardle at his home on various occasions between summer 1875 and spring 1878, mastering the processes of that art and making experiments in the revival of old or discovery of new methods. Deeming the colours to be of inferior quality, Morris rejected the chemical aniline dyes which were then predominant, instead emphasizing the revival of organic dyes. One result of these experiments was to reinstate indigo dyeing as a practical industry and generally to renew the use of those vegetable dyes, such as walnut shells and roots for brown, and cochineal, kermes, and madder for red, which had been driven almost out of use by the anilines. Dyeing of wools, silks, and cottons was the necessary preliminary to what he had much at heart, the production of woven and printed fabrics of the highest excellence. After learning the skills of dyeing, in the late 1870s Morris turned his attention to weaving, experimenting with silk weaving at Queen's Square. Morris's patterns for woven textiles, some of which were also machine made under ordinary commercial conditions, included intricate double-woven furnishing fabrics in which two sets of warps and wefts are interlinked to create complex gradations of colour and texture. Morris long dreamed of weaving tapestries in the medieval manner, which he called "the noblest of the weaving arts." In September 1879 he finished his first solo effort, a small piece called "Cabbage and Vine". Meanwhile he continued with his literary output. Morris translated his own version of Virgil's Aeneid, titling it The Aeneids of Vergil (1876). Although many translations were already available, often produced by trained Classicists, Morris claimed that his unique perspective was as "a poet not a pedant". He also continued producing translations of Icelandic tales with Magnússon. In summer 1876 Morris' daughter Jenny Morris was diagnosed with epilepsy. Refusing to allow her to be societally marginalised or institutionalised, as was common in the period, Morris insisted that she be cared for by the family. In 1877 Morris was approached by Oxford University and offered the largely honorary position of Professor of Poetry. He declined, asserting that he felt unqualified. In March 1877 he founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), which he personally referred to as "Anti-Scrape", to combat the increasing trend for restoration. That same spring, he opened a store at No. 449 Oxford Street and obtained new staff who were able to improve its professionalism; as a result, sales increased and its popularity grew. In April 1879 Morris moved the family home again, this time renting an 18th-century mansion on Hammersmith's Upper Mall in West London owned by the novelist George MacDonald, Morris would name it Kelmscott House and re-decorate it according to his own taste. In the House's grounds he set up a workshop, focusing on the production of hand-knotted carpets. He revived a number of dead techniques, and insisted on the use of good quality raw materials, almost all natural dyes, and hand processing, and insisted on learning the techniques of production prior to producing a design. Morris taught himself embroidery, working with wool on a frame custom-built from an old example. Once he had mastered the technique he trained his wife Jane, her sister Bessie Burden and others to execute designs to his specifications. When "embroideries of all kinds" were offered through Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. catalogues, church embroidery became and remained an important line of business for its successor companies into the twentieth century. By 1880, Morris & Co. had become a household name, having become very popular with Britain's upper and middle classes, obtaining increasing numbers of commissions from aristocrats, wealthy industrialists, and provincial entrepreneurs, with Morris furnishing parts of St James's Palace and the chapel at Eaton Hall. In summer 1881, Morris took out a lease on the seven-acre former silk weaving factory, the Merton Abbey Works, next to the River Wandle on the High Street at Merton, Southwest London. Moving his workshops to the site, the premises were used for weaving, dyeing, and creating stained glass; within three years, 100 craftsmen were employed there. Working conditions at the Abbey were better than at most Victorian factories. Rossetti died in April 1882. Jane, who continued her relationship with Rossetti through a correspondence and occasional visits, last saw him in 1881. Morris described his mixed feelings toward his deceased friend Rossetti by stating that he had "some of the very greatest qualities of genius, most of them indeed; what a great man he would have been but for the arrogant misanthropy which marred his work, and killed him before his time". In 1883, he opened up another store in Manchester and held a stand at that year's Foreign Fair in Boston, USA. In August 1883, His wife Jane was introduced to the poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, with whom she embarked on another affair. By now, William Morris has been increasingly involved in politics, devoting to the socialist cause, which meant he saw less of Burne-Jones who did not share his opinion, and less time for his literature pursuit. In April 1887, Reeves and Turner published the first volume of Morris' translation of Homer's Odyssey, with the second following in November. In December 1888, the Chiswick Press published Morris' The House of the Wolfings, a fantasy story set in Iron Age Europe which provides a reconstructed portrait of the lives of Germanic-speaking Gothic tribes. It contained both prose and aspects of poetic verse. A sequel, The Roots of the Mountains, followed in 1889. Over the coming years he would publish a string of other poetic works. Following the death of the sitting Poet Laureate of Great Britain and Ireland, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in October 1892, Morris was offered the position, but turned it down, disliking its associations with the monarchy and political establishment. Morris' influence on Britain's artistic community became increasingly apparent as the Art Workers' Guild was founded in 1884, although at the time he was too preoccupied with his socialist activism to pay it any attention. Morris was elected to the Guild in 1888, and to the position of master in 1892. The work of Morris & Co. continued during Morris' final years, producing an array of stained glass windows designed by Burne-Jones. In January 1891, Morris began renting a cottage near to Kelmscott House, which would serve as the first premises of the Kelmscott Press. Devoted to the production of books which he deemed beautiful, Morris was artistically influenced by the illustrated manuscripts and early printed books of Medieval and Early Modern Europe. It was his ambition to produce a perfect work to restore all the beauty of illuminated lettering, richness of gilding and grace of binding that used to make a volume the treasure of a king. His efforts were constantly directed towards giving the world at least one book that exceeded anything that had ever appeared. Before publishing its first work, Morris ensured that he had mastered the techniques of printing and secured the supplies of hand-made paper and binding materials necessary for production. As a result only the wealthy could purchase his lavish works; Morris realized that creating works in the manner of the middle ages was difficult in a profit-grinding society. Over the next seven years, they published 66 volumes, 23 of them are Morris' books, and editions of works by Keats, Shelley, Ruskin, and Swinburne, as well as copies of various Medieval texts. The Press' magnum opus was the Kelmscott Chaucer, which had taken years to complete and included 87 illustrations by Burne-Jones. The press was closed in 1898. The Kelmscott Press influenced much of the fine press movement in England and the United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It brought the need for books that were aesthetic objects as well as words to the attention of the reading and publishing worlds. By the early 1890s, Morris was increasingly ill and living largely as an invalid; aside from his gout, he also exhibited signs of epilepsy. In 1896, he became a complete invalid, being visited by friends and family, before dying of tuberculosis on the morning of 4 October 1896. Obituaries appearing throughout the national press reflected that at the time, Morris was widely recognised primarily as a poet. His funeral was held on 6 October, during which his corpse was carried from Hammersmith to Paddington rail station, where it was transported to Oxford, and from there to Kelmscott, where it was buried in the churchyard of St. George's Church. During his lifetime, apart from his prolific literature outputs both in writing and translation, William Morris produced items in a range of crafts, mainly those to do with furnishing, including over 600 designs for wall-paper, textiles, and embroideries, over 150 for stained glass windows, three typefaces, and around 650 borders and ornamentations for the Kelmscott Press. He emphasised the idea that the design and production of an item should not be divorced from one another, and that where possible those creating items should be designer-craftsmen, thereby both designing and manufacturing their goods.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|