|

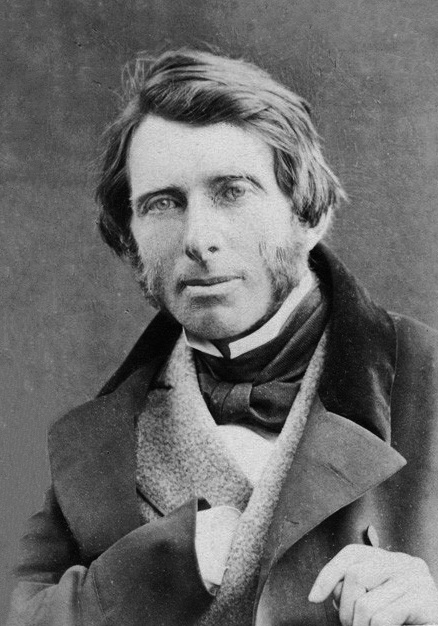

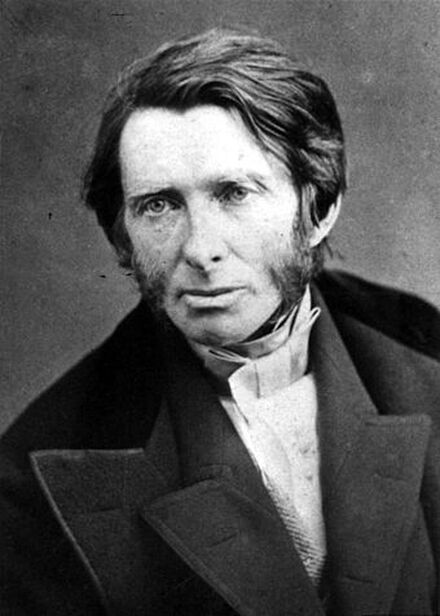

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 – 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher and art critic of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and political economy. Ruskin's writing styles and literary forms were equally varied. He wrote essays and treatises, poetry and lectures, travel guides and manuals, letters and even a fairy tale. He also made detailed sketches and paintings of rocks, plants, birds, landscapes, architectural structures and ornamentation. The elaborate style that characterised his earliest writing on art gave way in time to plainer language designed to communicate his ideas more effectively. In all of his writing, he emphasised the connections between nature, art and society. Ruskin was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century and up to the First World War. After a period of relative decline, his reputation has steadily improved since the 1960s with the publication of numerous academic studies of his work. Today, his ideas and concerns are widely recognised as having anticipated interest in environmentalism, sustainability and craft. Ruskin first came to widespread attention with the first volume of Modern Painters (1843), an extended essay in defence of the work of J. M. W. Turner in which he argued that the principal role of the artist is "truth to nature". From the 1850s, he championed the Pre-Raphaelites, who were influenced by his ideas. His work increasingly focused on social and political issues. Unto This Last (1860, 1862) marked the shift in his emphasis. In 1869, Ruskin became the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford, where he established the Ruskin School of Drawing. In 1871, he began his monthly "letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain", published under the title Fors Clavigera (1871–1884). In the course of this complex and deeply personal work, he developed the principles underlying his ideal society. As a result, he founded the Guild of St George, an organisation that endures today. BiographyJohn Ruskin was born on 8 February 1819 at 54 Hunter Street, Brunswick Square, London, the only child of his parents who were first cousins. His father, John James Ruskin (1785–1864), was a sherry and wine importer, founding partner and de facto business manager of Ruskin, Telford and Domecq. His mother Margaret Cock (1781–1871), was the daughter of a publican. She had joined the Ruskin household when she became companion to John James's mother, Catherine. They married, without celebration, in 1818. Ruskin's childhood was shaped by the contrasting influences of his father and mother, both of whom were fiercely ambitious for him. John James Ruskin helped to develop his son's Romanticism. They shared a passion for the works of Byron, Shakespeare and especially Walter Scott. Margaret Ruskin, an evangelical Christian, more cautious and restrained than her husband, taught young John to read the Bible from beginning to end, and then to start all over again, committing large portions to memory. Its language, imagery and parables had a profound and lasting effect on his writing. As a child Ruskin was educated at home by his parents and private tutors. From 1834 to 1835 he attended the school in Peckham run by the progressive evangelical Thomas Dale (1797–1870). Ruskin heard Dale lecture in 1836 at King's College, London, where Dale was the first Professor of English Literature. Ruskin went on to enroll and complete his studies at King's College, where he prepared for Oxford under Dale's tutelage. Ruskin was greatly influenced by the extensive and privileged travels he enjoyed in his childhood. It helped to establish his taste and augmented his education. He sometimes accompanied his father on visits to business clients at their country houses, which exposed him to English landscapes, architecture and paintings. As early as 1825, the family visited France and Belgium. He developed a lifelong love of the Alps, and in 1835 visited Venice for the first time, that 'Paradise of cities' that provided the subject and symbolism of much of his later work. These tours gave Ruskin the opportunity to observe and record his impressions of nature. He composed elegant, though mainly conventional poetry, some of which was published in Friendship's Offering. His early notebooks and sketchbooks are full of visually sophisticated and technically accomplished drawings of maps, landscapes and buildings, remarkable for a boy of his age. He was profoundly affected by Samuel Rogers's poem, Italy (1830), a copy of which was given to him as a 13th birthday present; in particular, he deeply admired the accompanying illustrations by J. M. W. Turner. Much of Ruskin's own art in the 1830s was in imitation of Turner, and of Samuel Prout, whose Sketches Made in Flanders and Germany (1833) he also admired. Ruskin's journeys also provided inspiration for his writing. His first publication was the poem "On Skiddaw and Derwent Water" (August 1829). In 1834, three short articles for Loudon's Magazine of Natural History were published. They show early signs of his skill as a close "scientific" observer of nature, especially its geology. From September 1837 to December 1838, Ruskin's The Poetry of Architecture was serialised in Loudon's Architectural Magazine, under the pen name "Kata Phusin" (Greek for "According to Nature"). It was a study of cottages, villas, and other dwellings centred on a Wordsworthian argument that buildings should be sympathetic to their immediate environment and use local materials. It anticipated key themes in his later writings. In 1839, Ruskin's "Remarks on the Present State of Meteorological Science" was published in Transactions of the Meteorological Society. In 1836, Ruskin matriculated at the University of Oxford. Enrolled as a gentleman-commoner, he enjoyed equal status with his aristocratic peers. Ruskin was generally uninspired by Oxford and suffered bouts of illness, and he never became independent from his family during his time at Oxford. In April 1840, whilst revising for his examinations, he began to cough blood, which led to fears of consumption and a long break from Oxford travelling with his parents. For much of the period from late 1840 to autumn 1842, Ruskin was abroad with his parents, mainly in Italy. Back at Oxford, in 1842 Ruskin sat for a pass degree, and was awarded an uncommon honorary double fourth-class degree in recognition of his achievements. Before Ruskin began Modern Painters, his father John James Ruskin had begun collecting watercolours, including works by Samuel Prout and J. M. W. Turner. Both painters were among occasional guests of the Ruskins. When Ruskin read an attack on several of Turner's pictures exhibited at the Royal Academy, he wrote a defence of Turner which finally appeared in 1903, as Turner did not wish it to be published. What became the first volume of Modern Painters (1843) was Ruskin's answer to Turner's critics. Ruskin controversially argued that modern landscape painters—and in particular Turner—were superior to the so-called "Old Masters" of the post-Renaissance period. Ruskin maintained that, unlike Turner, Old Masters such as Gaspard Dughet (Gaspar Poussin), Claude, and Salvator Rosa favoured pictorial convention, and not "truth to nature". For Ruskin, modern landscapists demonstrated superior understanding of the "truths" of water, air, clouds, stones, and vegetation, a profound appreciation of which Ruskin demonstrated in his own prose. Although critics were slow to react and the reviews were mixed, many notable literary and artistic figures were impressed with the young man's work, including Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Gaskell. Suddenly Ruskin had found his métier, and in one leap helped redefine the genre of art criticism, mixing a discourse of polemic with aesthetics, scientific observation and ethics. It cemented Ruskin's relationship with Turner. Ruskin toured the continent with his parents again in 1844, visiting Paris, studying the geology of the Alps and the paintings of Titian, Veronese and Perugino among others at the Louvre. In 1845, at the age of 26, he undertook to travel without his parents for the first time. It provided him with an opportunity to study medieval art and architecture in France, Switzerland and especially Italy. In Venice, he was particularly impressed by the works of Fra Angelico and Giotto in St Mark's Cathedral, and Tintoretto in the Scuola di San Rocco, but he was alarmed by the combined effects of decay and modernisation on the city. Drawing on his travels, he wrote the second volume of Modern Painters (published April 1846). The volume concentrated on Renaissance and pre-Renaissance artists rather than on Turner. It was a more theoretical work than its predecessor. Ruskin explicitly linked the aesthetic and the divine, arguing that truth, beauty and religion are inextricably bound together. In defining categories of beauty and imagination, Ruskin argued that all great artists must perceive beauty and, with their imagination, communicate it creatively by means of symbolic representation. During 1847, Ruskin became closer to Effie Gray, the daughter of family friends. It was for her that Ruskin had written The King of the Golden River, his only work of fiction, set in the Alpine landscape Ruskin loved and knew so well. It remains the most translated of all his works. The couple were engaged in October. They married on 10 April 1848 at her home, Bowerswell, in Perth, once the residence of the Ruskin family. The European Revolutions of 1848 meant that the newlyweds' earliest travels together were restricted, but they were able to visit Normandy, where Ruskin admired the Gothic architecture. Ruskin's developing interest in architecture, and particularly in the Gothic, led to the first work to bear his name, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849). It contained 14 plates etched by the author. The title refers to seven moral categories that Ruskin considered vital to and inseparable from all architecture: sacrifice, truth, power, beauty, life, memory and obedience. All would provide recurring themes in his work. In November 1849, Effie and John Ruskin visited Venice, staying at the Hotel Danieli. For Effie, Venice provided an opportunity to socialise, while Ruskin was engaged in solitary studies. Ruskin was making the extensive sketches and notes that he used for his three-volume work The Stones of Venice (1851–53). Developing from a technical history of Venetian architecture from the Romanesque to the Renaissance, into a broad cultural history, Stones reflected Ruskin's view of contemporary England. In 1848, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti had established the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The Pre-Raphaelite commitment to 'naturalism' – depicting nature in fine detail, had been influenced by Ruskin. Millais had painted Effie for The Order of Release, 1746, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1852. In the summer of 1853 John Everett Millais (and his brother) travelled to Scotland with Ruskin and Effie. She and Millais fell in love, and Effie left Ruskin, causing a public scandal. In April 1854, Effie filed her suit of nullity, on grounds of "non-consummation" owing to his "incurable impotency", a charge Ruskin later disputed. The annulment was granted in July. Ruskin did not even mention it in his diary. Effie married Millais the following year. The complex reasons for the non-consummation and ultimate failure of the Ruskin marriage are a matter of enduring speculation and debate. Ruskin continued to support Hunt and Rossetti as well as his wife Elizabeth to encourage her art. Other artists influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites also received both critical and financial support from Ruskin, including John Brett, John William Inchbold, and Edward Burne-Jones, who became a good friend. Ruskin had been in Venice when he heard about Turner's death in 1851. Being named an executor to Turner's will was an honour that Ruskin respectfully declined, but later took up. Ruskin's book in celebration of the sea, The Harbours of England, revolving around Turner's drawings, was published in 1856. In January 1857, Ruskin's Notes on the Turner Gallery at Marlborough House, 1856 was published. He persuaded the National Gallery to allow him to work on the Turner Bequest of nearly 20,000 individual artworks left to the nation by the artist. Starting from the 1850s Ruskin was involved in teaching and became an increasingly popular public lecturer. His first public lectures were given in Edinburgh, in November 1853, on architecture and painting. Both volumes III and IV of Modern Painters were published in 1856. During this period Ruskin wrote regular reviews of the annual exhibitions at the Royal Academy under the title Academy Notes (1855–59, 1875). They were highly influential, capable of making or breaking reputations. Following his crisis of faith, and influenced in part by his friend Thomas Carlyle (whom he had first met in 1850), Ruskin shifted his emphasis in the late 1850s from art towards social issues. Nevertheless, he continued to lecture on and write about a wide range of subjects including art. Ruskin was an art-philanthropist: in March 1861 he gave 48 Turner drawings to the Ashmolean in Oxford, and a further 25 to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge in May. On his father's death in 1864, Ruskin inherited a considerable fortune of between £120,000 and £157,000 This considerable fortune gave him the means to engage in personal philanthropy and practical schemes of social amelioration. Ruskin was unanimously appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University in August 1869. In Oxford, Ruskin's lectures were often so popular that they had to be given twice—once for the students, and again for the public. Most of them were eventually published. He lectured on a wide range of subjects at Oxford, his interpretation of "Art" encompassing almost every conceivable area of study. In 1871, John Ruskin founded his own art school at Oxford, The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. Ruskin endowed the drawing mastership with £5000 of his own money. He also established a large collection of drawings, watercolours and other materials (over 800 frames) that he used to illustrate his lectures. That same year, Ruskin also founded his utopian society, the Guild of St George. A communitarian protest against nineteenth-century industrial capitalism, it had a hierarchical structure, with Ruskin as its Master, and dedicated members called "Companions". Ruskin wished to show that contemporary life could still be enjoyed in the countryside, with land being farmed by traditional means, in harmony with the environment, and with the minimum of mechanical assistance. He also sought to educate and enrich the lives of industrial workers by inspiring them with beautiful objects. As such, with a tithe (or personal donation) of £7,000, Ruskin acquired land and a collection of art treasures. Donations of land from wealthy and dedicated Companions eventually placed land and property in the Guild's care. In principle, Ruskin worked out a scheme for different grades of "Companion", wrote codes of practice, described styles of dress and even designed the Guild's own coins. In reality, the Guild, which still exists today as a charitable education trust, has only ever operated on a small scale. The Guild's most conspicuous and enduring achievement was the creation of a remarkable collection of art, minerals, books, medieval manuscripts, architectural casts, coins and other precious and beautiful objects. In August 1871, Ruskin purchased the then somewhat dilapidated Brantwood house, on the shores of Coniston Water, in the English Lake District, paying £1500 for it. Brantwood was Ruskin's main home from 1872 until his death. His estate provided a site for more of his practical schemes and experiments: he had an ice house built, and the gardens comprehensively rearranged. He oversaw the construction of a larger harbour (from where he rowed his boat, the Jumping Jenny), and he altered the house (adding a dining room, a turret to his bedroom to give him a panoramic view of the lake, and he later extended the property to accommodate his relatives). He built a reservoir, and redirected the waterfall down the hills, adding a slate seat that faced the tumbling stream and craggy rocks rather than the lake, so that he could closely observe the fauna and flora of the hillside. Ruskin had been introduced to the wealthy Irish La Touche family by Louisa, Marchioness of Waterford. Maria La Touche, a minor Irish poet and novelist, asked Ruskin to teach her daughters drawing and painting in 1858. Rose La Touche was ten. His first meeting came at a time when Ruskin's own religious faith was under strain. La Touche family prevented the two from meeting. A chance meeting at the Royal Academy in 1869 was one of the few occasions they came into personal contact. After a long illness, she died on 25 May 1875, at the age of 27. These events plunged Ruskin into despair and led to increasingly severe bouts of mental illness involving a number of breakdowns and delirious visions. Ruskin turned to spiritualism. He attended seances at Broadlands. Ruskin's increasing need to believe in a meaningful universe and a life after death, both for himself and his loved ones, helped to revive his Christian faith in the 1870s. In 1879, Ruskin resigned from Oxford, but resumed his Professorship in 1883, only to resign again in 1884. In the 1880s, Ruskin returned to some literature and themes that had been among his favourites since childhood. He wrote about Scott, Byron and Wordsworth in Fiction, Fair and Foul (1880). His last great work was his autobiography, Praeterita (1885–89) (meaning, 'Of Past Things'), a highly personalised, selective, eloquent but incomplete account of aspects of his life. The period from the late 1880s was one of steady and inexorable decline. Gradually it became too difficult for him to travel to Europe. He suffered a complete mental collapse on his final tour, which included Beauvais, Sallanches and Venice, in 1888. The emergence and dominance of the Aesthetic movement and Impressionism distanced Ruskin from the modern art world, his ideas on the social utility of art contrasting with the doctrine of "l'art pour l'art" or "art for art's sake" that was beginning to dominate. Although Ruskin's 80th birthday was widely celebrated in 1899, Ruskin was scarcely aware of it. He died at Brantwood from influenza on 20 January 1900 at the age of 80. He was buried five days later in the churchyard at Coniston, according to his wishes. The contents of Ruskin's home were dispersed in a series of sales at auction, and Brantwood itself was bought in 1932 by the educationist and Ruskin enthusiast, collector and memorialist, John Howard Whitehouse who opened in 1934 as a memorial to Ruskin and it remains open to the public today. The Guild of St George continues to thrive as an educational charity, and has an international membership. Ruskin's influence reached across the world. Tolstoy described him as "one of the most remarkable men not only of England and of our generation, but of all countries and times" and quoted extensively from him, rendering his ideas into Russian. Proust not only admired Ruskin but helped translate his works into French. Gandhi wrote of the "magic spell" cast on him by Unto This Last and paraphrased the work in Gujarati, calling it Sarvodaya, "The Advancement of All". Theorists and practitioners in a broad range of disciplines acknowledged their debt to Ruskin. Architects including Le Corbusier, Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Gropius incorporated his ideas in their work. Writers as diverse as Oscar Wilde, G. K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, T. S. Eliot, W. B. Yeats and Ezra Pound felt Ruskin's influence.

William Morris and C. R. Ashbee (of the Guild of Handicraft) were keen disciples, and through them Ruskin's legacy can be traced in the arts and crafts movement.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|