|

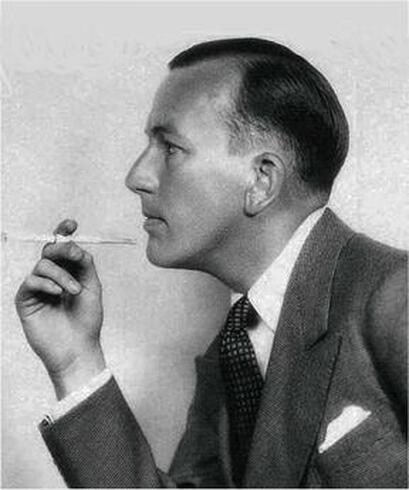

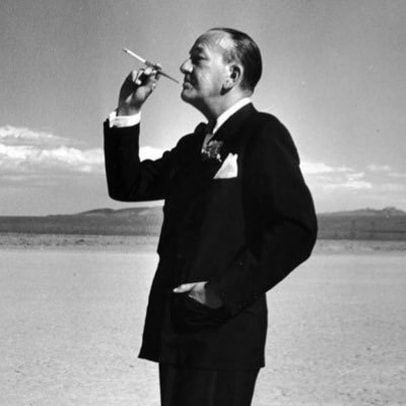

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 1899 – 26 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what Time magazine called "a sense of personal style, a combination of cheek and chic, pose and poise". Coward attended a dance academy in London as a child, making his professional stage début at the age of eleven. As a teenager he was introduced into the high society in which most of his plays would be set. Coward achieved enduring success as a playwright, publishing more than 50 plays from his teens onwards. Many of his works, such as Hay Fever, Private Lives, Design for Living, Present Laughter and Blithe Spirit, have remained in the regular theatre repertoire. He composed hundreds of songs, in addition to well over a dozen musical theatre works (including the operetta Bitter Sweet and comic revues), screenplays, poetry, several volumes of short stories, the novel Pomp and Circumstance, and a three-volume autobiography. Coward's stage and film acting and directing career spanned six decades, during which he starred in many of his own works, as well as those of others. At the outbreak of the Second World War Coward volunteered for war work, running the British propaganda office in Paris. He also worked with the Secret Service, seeking to use his influence to persuade the American public and government to help Britain. Coward won an Academy Honorary Award in 1943 for his naval film drama In Which We Serve and was knighted in 1969. In the 1950s he achieved fresh success as a cabaret performer, performing his own songs, such as "Mad Dogs and Englishmen", "London Pride" and "I Went to a Marvellous Party". Coward's plays and songs achieved new popularity in the 1960s and 1970s, and his work and style continue to influence popular culture. He did not publicly acknowledge his homosexuality, but it was discussed candidly after his death by biographers including Graham Payn, his long-time partner, and in Coward's diaries and letters, published posthumously. The former Albery Theatre (originally the New Theatre) in London was renamed the Noël Coward Theatre in his honour in 2006. BiographyNoel Coward was born in 1899 in Teddington, Middlesex, a south-western suburb of London. His parents were Arthur Sabin Coward (1856–1937), a piano salesman, and Violet Agnes Coward (1863–1954), daughter of Henry Gordon Veitch, a captain and surveyor in the Royal Navy. Noël Coward was the second of their three sons. Coward's father lacked ambition and industry, and family finances were often poor. Coward was bitten by the performing bug early and appeared in amateur concerts by the age of seven. He attended the Chapel Royal Choir School as a young child. He had little formal schooling but was a voracious reader. Encouraged by his ambitious mother, who sent him to a dance academy in London, Coward's first professional engagement was in January 1911 as Prince Mussel in the children's play The Goldfish. In 1912 Coward was cast as the Lost Boy Slightly in Peter Pan. He reappeared in Peter Pan the following year. He worked with other child actors in this period, including Gertrude Lawrence who, Coward wrote in his memoirs, "gave me an orange and told me a few mildly dirty stories, and I loved her from then onwards." In 1914, when Coward was fourteen, he became the protégé and probably the lover of Philip Streatfeild, a society painter. Streatfeild introduced him to Mrs Astley Cooper and her high society friends. Streatfeild died from tuberculosis in 1915, but Mrs Astley Cooper continued to encourage her late friend's protégé, who remained a frequent guest at her estate, Hambleton Hall in Rutland. Coward continued to perform during most of the First World War. In 1918, Coward was conscripted into the Artists Rifles but was assessed as unfit for active service because of a tubercular tendency, and he was discharged on health grounds after nine months. That year he appeared in the D. W. Griffith film Hearts of the World in an uncredited role. He sold short stories to several magazines to help his family financially. He also began writing plays. His first solo effort as a playwright was The Rat Trap (1918) which was eventually produced at the Everyman Theatre, Hampstead, in October 1926. During these years, he met Lorn McNaughtan, who became his private secretary and served in that capacity for more than forty years, until her death. In 1920, at the age of 20, Coward starred in his own play, the light comedy I'll Leave It to You. After a three-week run in Manchester it opened in London at the New Theatre (renamed the Noël Coward Theatre in 2006), his first full-length play in the West End. The play ran for a month after which Coward returned to acting in works by other writers. In 1921, Coward made his first trip to America, hoping to interest producers there in his plays. Although he had little luck, he found the Broadway theatre stimulating. He absorbed its smartness and pace into his own work, which brought him his first real success as a playwright with The Young Idea. The play opened in London in 1923, after a provincial tour, with Coward in one of the leading roles. The play ran in London from 1 February to 24 March 1923, after which Coward turned to revue. In 1924, Coward achieved his first great critical and financial success as a playwright with The Vortex. The story is about a nymphomaniac socialite and her cocaine-addicted son (played by Coward). The Vortex was considered shocking in its day for its depiction of sexual vanity and drug abuse among the upper classes. Its notoriety and fiery performances attracted large audiences, justifying a move from a small suburban theatre to a larger one in the West End. Coward, still having trouble finding producers, raised the money to produce the play himself. During the run of The Vortex, Coward met Jack Wilson, an American stockbroker (later a director and producer), who became his business manager and lover. Wilson abused his position to steal from Coward, but the playwright was in love and accepted both the larceny and Wilson's heavy drinking. The success of The Vortex in both London and America caused a great demand for new Coward plays. Hay Fever, the first of Coward's plays to gain an enduring place in the mainstream theatrical repertoire, appeared in 1925. It is a comedy about four egocentric members of an artistic family who casually invite acquaintances to their country house for the weekend and bemuse and enrage each other's guests. By the 1970s the play was recognised as a classic. By June 1925 Coward had four shows running in the West End: The Vortex, Fallen Angels, Hay Fever and On with the Dance. Coward was turning out numerous plays and acting in his own works and others'. Soon, his frantic pace caught up with him, and he collapsed on stage in 1926 while starring in a stage adaptation of The Constant Nymph and had to take an extended rest, recuperating in Hawaii. Other Coward works produced in the mid-to-late 1920s included the plays such as Easy Virtue (1926), a drama about a divorcée's clash with her snobbish in-laws; The Marquise (1927), an eighteenth-century costume drama; His biggest failure in this period was the play Sirocco (1927), which concerns free love among the wealthy. In 1926, Coward acquired Goldenhurst Farm, in Aldington, Kent, making it his home for most of the next thirty years, except when the military used it during the Second World War. It is a Grade II listed building. By 1929 Coward was one of the world's highest-earning writers, with an annual income of £50,000, more than £2,800,000 in terms of 2018 values. Coward thrived during the Great Depression, writing a succession of popular hits. They ranged from large-scale spectaculars to intimate comedies. His historical extravaganza Cavalcade (1931) about thirty years in the lives of two families, was adapted into a film and won the Academy Award for best picture in 1933. Coward's intimate-scale hits of the period included Private Lives (1930) and Design for Living (1932). In Private Lives, Coward starred alongside his most famous stage partner, Gertrude Lawrence, together with the young Laurence Olivier. It was a highlight of both Coward's and Lawrence's career, selling out in both London and New York. Coward disliked long runs, and after this he made a rule of starring in a play for no more than three months at any venue. Design for Living, written for Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, was so risqué, with its theme of bisexuality and a ménage à trois, that Coward premiered it in New York, knowing that it would not survive the censor in London. In 1936 Coward wrote, directed and co-starred with Lawrence in Tonight at 8.30 (1936), a cycle of ten short plays. One of these plays, Still Life, was expanded into the 1945 David Lean film Brief Encounter. Coward's last pre-war plays were This Happy Breed, a drama about a working-class family, and Present Laughter, a comic self-caricature with an egomaniac actor as the central character. These were first performed in 1942, although they were both written in 1939. With the outbreak of the Second World War Coward abandoned the theatre and sought official war work. After running the British propaganda office in Paris, he worked on behalf of British intelligence. His task was to use his celebrity to influence American public and political opinion in favour of helping Britain. He was frustrated by British press criticism of his foreign travel while his countrymen suffered at home, but he was unable to reveal that he was acting on behalf of the Secret Service. In 1942 George VI wished to award Coward a knighthood for his efforts, but was dissuaded by Winston Churchill. Coward then followed advice of Churchill of entertaining the troops and the home front instead of continuing his intelligence work. He toured, acted and sang indefatigably in Europe, Africa, Asia and America. His London home was wrecked by German bombs in 1941, and he took up temporary residence at the Savoy Hotel. Another of Coward's wartime projects, as writer, star, composer and co-director (alongside David Lean), was the naval film drama In Which We Serve. The film was popular on both sides of the Atlantic, and he was awarded an honorary certificate of merit at the 1943 Academy Awards ceremony. Coward played a naval captain, basing the character on his friend Lord Louis Mountbatten. David Lean went on to direct and adapt film versions of several Coward plays. Coward's most enduring work from the war years was the hugely successful black comedy Blithe Spirit (1941), about a novelist who researches the occult and hires a medium. A séance brings back the ghost of his first wife, causing havoc for the novelist and his second wife. With 1,997 consecutive performances, it broke box-office records for the run of a West End comedy, and was also produced on Broadway, where its original run was 650 performances. The play was adapted into a 1945 film, directed by Lean. Coward's new plays after the war were moderately successful but failed to match the popularity of his pre-war hits. Relative Values (1951) addresses the culture clash between an aristocratic English family and a Hollywood actress with matrimonial ambitions; South Sea Bubble (1951) is a political comedy set in a British colony; Quadrille (1952) is a drama about Victorian love and elopement; Further blows in this period were the deaths of Coward's friends Charles Cochran and Gertrude Lawrence, in 1951 and 1952 respectively. Despite his disappointments, Coward maintained a high public profile. In 1955 Coward's cabaret act at Las Vegas, recorded live for the gramophone, and released as Noël Coward at Las Vegas, was so successful that CBS engaged him to write and direct a series of three 90-minute television specials for the 1955–56 season. including productions of Blithe Spirit in which he starred with Claudette Colbert and Lauren Bacall. In the 1950s, Coward left the UK for tax reasons, receiving harsh criticism in the press. He first settled in Bermuda but later bought houses in Jamaica and Switzerland (in the village of Les Avants, near Montreux), which remained his homes for the rest of his life. His expatriate neighbours and friends included Joan Sutherland, David Niven, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, and Julie Andrews and Blake Edwards in Switzerland and Ian Fleming and his wife Ann in Jamaica. Coward was a witness at the Flemings' wedding, but his diaries record his exasperation with their constant bickering. During the 1950s and 1960s Coward continued to write musicals and plays. Sail Away (1961), set on a luxury cruise liner, was Coward's most successful post-war musical, with productions in America, Britain and Australia. He directed the successful 1964 Broadway musical adaptation of Blithe Spirit, called High Spirits. Coward's final stage success came with Suite in Three Keys (1966), a trilogy set in a hotel penthouse suite. He wrote it as his swan song as a stage actor. In one of the three plays, A Song at Twilight, Coward abandoned his customary reticence on the subject and played an explicitly homosexual character. The daring piece earned Coward new critical praise. Coward won new popularity in several notable films later in his career, such as Around the World in 80 Days (1956), Our Man in Havana (1959), Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965), Boom! (1968) and The Italian Job (1969). He refused to play the title role in the 1962 film Dr. No, and the role of Colonel Nicholson in the film The Bridge on the River Kwai, as well as the role of the king in the original stage production of The King and I. He also refused to compose a musical version of Pygmalion (two years before My Fair Lady was written). By the end of the 1960s, Coward suffered from arteriosclerosis and, during the run of Suite in Three Keys, he struggled with bouts of memory loss. This also affected his work in The Italian Job, and he retired from acting immediately afterwards. Coward was knighted in 1970, and was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. That same year he also received a Tony Award for lifetime achievement. Coward died at his home, Firefly Estate, in Jamaica on 26 March 1973 of heart failure and was buried three days later on the brow of Firefly Hill, overlooking the north coast of the island. A memorial service was held in St Martin-in-the-Fields in London on 29 May 1973. John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier read verse and Yehudi Menuhin played Bach. There are probably greater painters than Noël, greater novelists than Noël, greater librettists, greater composers of music, greater singers, greater dancers, greater comedians, greater tragedians, greater stage producers, greater film directors, greater cabaret artists, greater TV stars. If there are, they are fourteen different people. Only one man combined all fourteen different labels – The Master." Coward was homosexual but, following the convention of his times, this was never publicly mentioned. Even in the 1960s, Coward refused to acknowledge his sexual orientation publicly. Despite this reticence, he encouraged his secretary Cole Lesley to write a frank biography once Coward was safely dead. Coward's most important relationship, which began in the mid-1940s and lasted until his death, was with the South African stage and film actor Graham Payn. Coward featured Payn in several of his London productions. Payn later co-edited with Sheridan Morley a collection of Coward's diaries, published in 1982. Coward's other relationships included the playwright Keith Winter, actors Louis Hayward and Alan Webb, his manager Jack Wilson and the composer Ned Rorem, who published details of their relationship in his diaries. Coward had a 19-year friendship with Prince George, Duke of Kent, but biographers differ on whether it was platonic. Payn believed that it was, although Coward reportedly admitted to the historian Michael Thornton that there had been "a little dalliance". Coward maintained close friendships with many women, including the actress and author Esmé Wynne-Tyson, his first collaborator and constant correspondent; Gladys Calthrop, who designed sets and costumes for many of his works; his secretary and close confidante Lorn Loraine; the actresses Gertrude Lawrence, Joyce Carey and Judy Campbell; and "his loyal and lifelong amitié amoureuse", Marlene Dietrich. In his profession, Coward was widely admired and loved for his generosity and kindness to those who fell on hard times. Stories are told of the unobtrusive way in which he relieved the needs or paid the debts of old theatrical acquaintances who had no claim on him. As soon as he achieved success he began polishing the Coward image: an early press photograph showed him sitting up in bed holding a cigarette holder: "I looked like an advanced Chinese decadent in the last phases of dope."[147] Soon after that, Coward wrote, "I took to wearing coloured turtle-necked jerseys, actually more for comfort than for effect, and soon I was informed by my evening paper that I had started a fashion. I believe that to a certain extent this was true; at any rate, during the ensuing months I noticed more and more of our seedier West-End chorus boys parading about London in them." He soon became more cautious about overdoing the flamboyance, advising Cecil Beaton to tone down his outfits: "It is important not to let the public have a loophole to lampoon you." However, Coward was happy to generate publicity from his lifestyle. In 1969 he told Time magazine, "I acted up like crazy. I did everything that was expected of me. Part of the job." Time concluded, "Coward's greatest single gift has not been writing or composing, not acting or directing, but projecting a sense of personal style, a combination of cheek and chic, pose and poise." A symposium published in 1999 to mark the centenary of Coward's birth listed some of his major productions scheduled for the year in Britain and North America, including Ace of Clubs, After the Ball, Blithe Spirit, Cavalcade, Easy Virtue, Hay Fever, Present Laughter, Private Lives, Sail Away, A Song at Twilight, The Young Idea and Waiting in the Wings. In another tribute, Tim Rice said of Coward's songs: "The wit and wisdom of Noël Coward's lyrics will be as lively and contemporary in 100 years' time as they are today". Coward's music, writings, characteristic voice and style have been widely parodied and imitated. Coward has frequently been depicted as a character in plays, films, television and radio shows. The Noël Coward Theatre in St Martin's Lane, originally opened in 1903 as the New Theatre and later called the Albery, was renamed in his honour after extensive refurbishment, re-opening on 1 June 2006. In 2008 an exhibition devoted to Coward was mounted at the National Theatre in London.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|