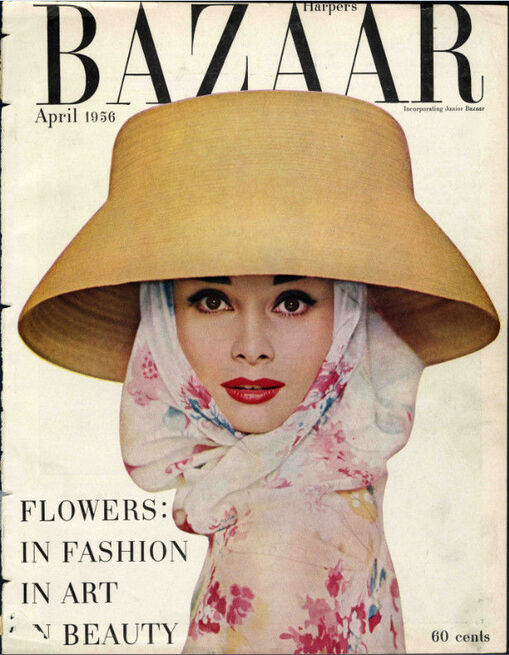

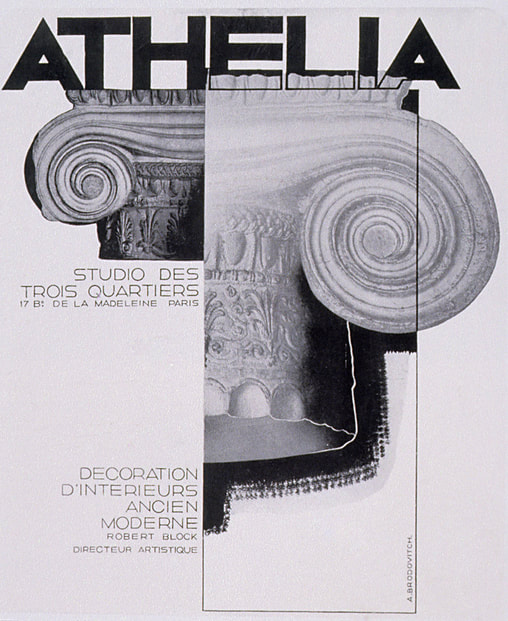

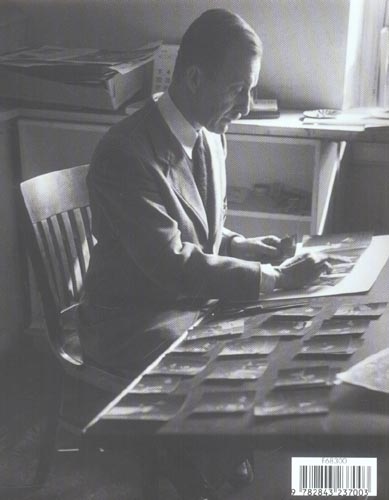

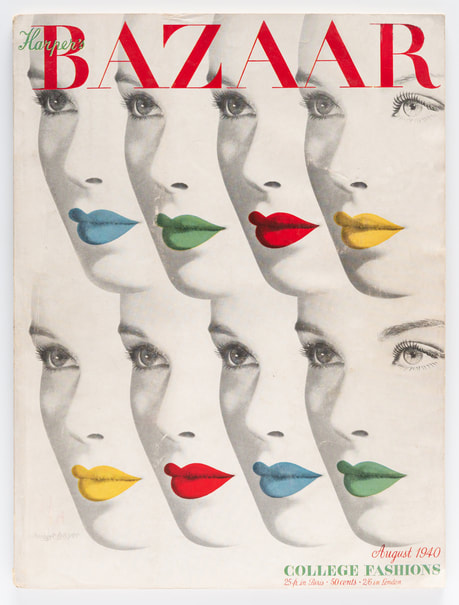

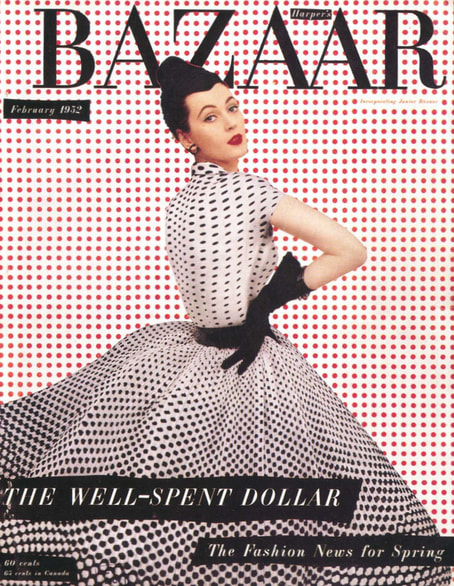

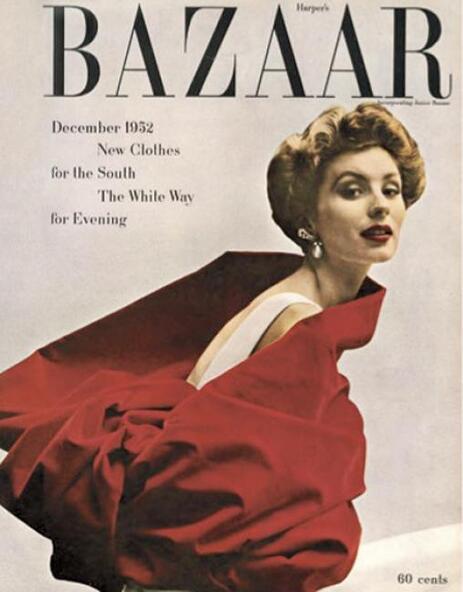

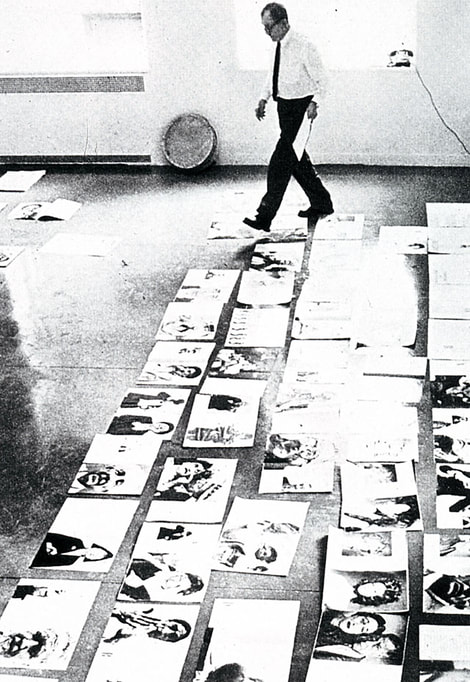

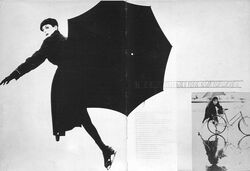

ProfileAlexey Vyacheslavovich Brodovitch/Brodovich(1898 – April 15, 1971) was an Russian-born American photographer, designer and instructor who is most famous for his art direction of fashion magazine Harper's Bazaar from 1934 to 1958. BiographyAlexey Brodovitch was born in Ogolichi, Оголичи Aholičy, Russian Empire (now Belarus) to a wealthy Polish family in May 1898. His father was a respected physician, psychiatrist and huntsman. His mother was an amateur painter. During the Russo-Japanese War, his family moved to Moscow, where Alexey was sent to study at the Prince Tenisheff School, a prestigious institution in Saint Petersburg, with the intentions of eventually enrolling in the Imperial Art Academy. He had no formal training in art through his childhood, but often sketched noble profiles in the audience at concerts in the city. At the start of World War I at the young age of 16, Brodovitch abandoned his dream of entering the Imperial Art Academy and ran away from home to join the Russian army. Not long after, his father had him brought home and hired a private tutor to help Alexey finish school. Upon graduating, Brodovitch ran away again on several occasions. He recalls: After a week or so I ran away to the front line to kill Germans. But my father, now a military general at the head of a Red Cross hospital train, had plenty of influence, and I was soon brought back to him. On the train back I was employed as a nurses' aid. In East Prussia I ran away again and joined a nearby regiment. Once again I was caught, and this time I was sent to an officers' school, the Corps de Pages. During the Russian Civil War, Brodovitch served with the White Army. While fighting against the Bolsheviks in Odessa, he was badly wounded and was hospitalized for a time in Kislovodsk, in the Caucasus. In 1918, the town was surrounded by the Bolsheviks, forcing Brodovitch into exile. It was during this retreat to the south through Caucasus and Turkey that he met his future wife, Nina. By good fortune, Alexey's brother Nicolas turned out to be one of the soldiers guarding the refugees in Novorossiysk. Not long after, their father, who had been imprisoned in Saint Petersburg by the Bolsheviks, managed to flee to Novorossiysk in hopes of finding his family. The three were once again together, and arranged for Brodovitch's mother and other relations to join them in Constantinople. Finally reunited, the Brodovitchs made their way to France. Upon arriving in Paris, Brodovitch wanted to be a painter. A Russian white émigré in Paris, Brodovitch found himself poor and having to work for the first time in his life. He took a job painting houses, while his wife Nina worked as a seamstress. They lived in a cheap, small apartment in the area of Montparnasse, among Russian artists who had settled in Paris at the end of the 19th century. This group of artists, including Archipenko, Chagall, and Nathan Altman, would meet at the inexpensive Académie Vassilieff, which offered painting and sculpting classes without an instructor. His connections with these young Russian artists led to more artistic work as a painter of backdrops for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Paris was a cosmopolitan city through which many artists and art movements passed. Brodovitch was exposed to everything from Dadaism from Zurich and Berlin, Suprematism and Constructivism from Moscow, Bauhaus design from Germany, Futurism from Italy, De Stijl from the Netherlands, and the native strains of Cubism, Fauvism, Purism and Surrealism. Among these various artistic influences, Brodovitch found his beginnings as a designer. On nights and weekends away from the Ballets Russes, Brodovitch began sketching designs for textiles, china, and jewelry. By the time his work for the ballet had finished, he had already compiled an extensive portfolio of these side projects and was selling his designs to fashionable shops. He worked part-time doing layouts for Cahiers d'Art, an important art journal, and Arts et Métiers Graphiques, an influential design magazine. While working on layouts, Brodovitch was responsible for fitting together type, photographs, and illustrations on the pages of the magazines. He had the rare opportunity of having influence over the look of the magazine as there was no art director. He gained public recognition for his work in the commercial arts by winning first prize in a poster competition for an artists' soiree called Le Bal Banal on March 24, 1924. The poster was exhibited on walls all over Montparnasse along with a drawing by Picasso, who took second place. Brodovitch remained proud of this poster throughout his career, always keeping a copy of it pinned to his studio wall. The graphic, light-to-dark inversion of its mask shape, type, and background suggest not only the process of photography, but also represents the process of trading one's identity for another when wearing a mask. It is the oldest surviving work by Brodovitch. He continued to gain recognition as an applied artist due to his success at the Paris International Exhibit of the Decorative Arts in 1925. He received five medals: three gold medals for kiosk design and jewelry, two silver medals for fabrics, and the top award for the Beck Fils pavilion "Amour de l'Art." After these wins, Brodovitch's career as an applied artist took off. In 1928 he was hired by Athélia, the design studio of the Parisian department store Aux Trois Quartiers, to design and illustrate catalogues and advertisements for their luxury men's boutique, Madelios. Brodovitch was aware that many of the customers were fairly traditional in their tastes, so he balanced out his modern designs with classical Greek references. Although employed full-time by Athélia, Brodovitch offered his service as a freelance designer on the side. He started his own studio, L'Atelier A.B., where he produced posters for various clients, including Union Radio Paris and the Cunard shipping company. He was also commissioned by the Parisian publishing house La Pléiade to illustrate three books: Nouvelles by Alexander Pushkin, Contes Fantastiques by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and Monsieur de Bougrelon by Jean Lorrain. Brodovitch embraced technical developments from the spheres of industrial design, photography, and contemporary painting. His broad curiosity began to assimilate the most interesting aspects of all these fields into his work, eventually making them his own. He later instilled this same curiosity in his students, encouraging them to use new techniques like the airbrush, industrial lacquers, flexible steel needles, and surgical knives. By the age of 32, Brodovitch had dabbled in producing posters, china, jewelry, textiles, advertisements, and paintings. Eventually specializing in advertising and graphic design, he had become one of the most respected designers of commercial art in Paris. By 1930, however, Paris had lost its luster for Brodovitch. The once-flourishing spirit of adventure and experimentation was fading away. Although he was offered many design positions, Brodovitch turned them down, presumably looking for new locales to advance his designs. While still living in Paris, Brodovitch was offered a job by John Story Jenks, a trustee of the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art (currently the University of the Arts), who was overwhelmed by Brodovitch's talents and asked him to head the school's Advertising Design Department. In September 1930, Brodovitch moved to Philadelphia with his wife and son to take the job. Brodovitch began teaching advertising design, creating a special department devoted to the subject. Brodovitch's task was to bring American advertising design up to the level of Europe's, which was thought to have a far more modern spirit. Before his arrival, advertising students were simply copying the magazine styles of N. C. Wyeth and Howard Pyle. The illustrations were beautiful, but had evolved from the tradition of 19th-century romantic realism, a thing of the past. Brodovitch's teaching technique, on the other hand, was unlike any other the students had been exposed to. He would always teach with a visual aid. Brodovitch would bring into class French and German magazines to examine the pages with his students, explaining the artist's work or technique. He would raise questions like, "Could this line be better? Could it be like, for example, Cocteau?" When not in the classroom, Brodovitch would take the class on outings around Philadelphia to see factories, laboratories, shopping centers, housing projects, dumps, and the zoo. The students were then told to make a "graphic impression" of what they had seen, whether a photographic interpretation, a drawing, or an abstraction. Brodovitch did not teach in the conventional sense, but rather compelled his students to discover one's inner, creative resources. "Brodovitch said "astonish me" many times, and he said we must enter the future and constantly change the old and seek the new. My own BREAKING THE LIGHT images reinvent the art of photography for the digital age, just as he urged all his students and all who worked with him to do. He despised imitation of the past and said long ago that we must be like the Russian Astronaut Gagarin and rocked into the future with daring and passion. He was a giant ahead of his time and he planted seeds of creativity that like the dragon seeds sprung up fully armored, and ready to astonish him." In 1933, Brodovitch added the Design Laboratory to the classes he offered. It was meant to be a workshop for his advanced students who wanted to experiment with all aspects of design. Brodovitch shared the Bauhaus belief that you needed to educate the whole individual by directing his or her attention to a variety of modern solutions in their graphic projects. His course description for the Design Laboratory read: The aim of the course is to help the student to discover his individuality, crystallize his taste, and develop his feeling for the contemporary trend by stimulating his sense of invention and perfecting his technical ability. The course is conducted as an experimental laboratory, inspired by the ever-changing tempo of life, discovery of new techniques, new fields of operation ... in close contact with current problems of leading magazines, department stores, advertising agencies and manufactures. Subjects include design, layout, type, poster, reportage, illustration, magazine make-up, package and product design, display, styling, art directing. "The Alexey Brodovitch course ... really changed the direction of my life. It was not anything that Brodovitch taught specifically, it was an ambiance that he created, a connection that he would make with particular students. He'd try to get them to move in directions that they were already discovering." The lab was split into two sections per week, one for design and one for photography. The workshops were immensely popular, and it was not unusual for more than sixty people to show up to his class on the first night. Among the photographers who attended his classes were Diane Arbus, Eve Arnold, David Attie, Richard Avedon, Harvey Lloyd, Hiro, Lisette Model, Garry Winogrand, Joel Meyerowitz and Tony Ray-Jones. "I learned from him that if, when you look in your camera, you see an image you have ever seen before, don't click the shutter." Graduates of these early courses went on to prominent careers in the field. Brodovitch's department came to be known as a 'prep school' for agencies and magazines around the country. "He taught me to be intolerant of mediocrity. He taught me to worship the unknown." I saw a fresh, new conception of layout technique that struck me like a revelation: pages that "bled" beautifully cropped photographs, typography and design that were bold and arresting. Within ten minutes I had asked Brodovitch to have cocktails with me, and that evening I signed him to a provisional contract as art director." In spring of 1934, the Art Directors Club of New York asked Brodovitch to design their "13th Annual Art Directors Exhibition" at the Rockefeller Center, New York. It was there that Carmel Snow, the recently appointed editor-in-chief of Harper's Bazaar, saw Brodovitch's work for the first time. She knew right away that Brodovitch would be the one to transform the magazine into a real revival of Vogue, where she had started her career. The offer was, of course, dependent on the approval of the owner of Harper's Bazaar, William Randolph Hearst. Brodovitch eagerly returned to Philadelphia and assigned his students apprenticing at his Van Pelt Street studio to make two dummy issues of the magazine. He insisted that each page have a "shock value" of its own to set the magazine apart, "cutting paper dolls out of patterned paper, or illustration perfume bottles to look like high key photography - whatever was unlike other fashion magazines was tried." Although preferring more conservative design, Hearst put his trust in Carmel Snow and allowed her to take on Brodovitch as art director where he remained for 24 years. The new look of Harper's Bazaar emphasized culture for its own sake. Taking advantage of Brodovitch's contacts in Europe and his wide knowledge of photography, the magazine introduced the work of many artists and photographers to its American audience. Before starting at Harper's Bazaar, Brodovitch organized a return trip to France, hoping to convince old friends to work with him at the magazine. Each summer he would return to offer commissions to artists and photographers until 1939 when the start of World War II made it impossible. By continually bringing in creative forces from overseas, he kept the magazine permanently fresh and cutting-edge. Among the artists that worked for Bazaar were Jean Cocteau, Raoul Dufy, Leonor Fini, Marc Chagall, Man Ray and A. M. Cassandre, the most eminent poster artist in France at the time, replacing the former cover favorite, Erté. Between 1935 and 1937, Brodovitch photographed several ballet companies, including the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, during their visits to New York on world tours. Although at the time he claimed the photos were only meant to be souvenirs, they evolved into something greater. The style in which Brodovitch photographed deviated from the sharp, straight photography popular at the time. According to one colleague, his images "spat in the face of technique and pointed out a new way in which photographers could work." Brodovitch released a book of these photographs in 1945, titled simply Ballet, through a small New York publisher. The book contains 104 photographs of several ballets and is divided into eleven segments, one for each ballet performance. On the contents page, Brodovitch introduces each chapter in a typographic style that emulates the feel of the dance it is describing. He photographed with a Contax 35mm camera, no flash, and with a slow film speed. The blurred figures of the dancers allow the viewer to not only feel the music, but also to follow the line of the dancer's limbs mid-step. The images beautifully capture the atmosphere on-stage, the frenzied behind-the-scenes action backstage, and the magical moments of the ballet. By bleeding the blurred, grainy pictures off the pages and into the gutters, he communicated the emotional impact of the dance without words. It was a pleasure to watch him work. He was so swift and sure. In emergencies, like the time the Clipper bearing the report of the Paris Collections was held up in Bermuda, his speed was dazzling. A quick splash or two on the cutting board, a minute's juggling of the photostats, a slather of art gum, and the sixteen pages were complete. His layouts, of course, were the despair of copywriters whose cherished tone poems on girdles or minks had to be sacrificed to his sacred white space. Just before we went to press, all the layouts were laid out in sequence on Carmel Snow's floor, and there, under his eye, re-arranged until the rhythm of the magazine suited him. To those who worked with him at Bazaar, the pinnacle of Brodovitch's career as a designer was the unfailing elegance of his pages. This elegance, combined with an element of innovation was the ideal mix for a fashion magazine. The quality that guaranteed his success was his devotion to the new, unending surprise and vitality. Typically, Brodovitch would begin his layouts by designing the layouts as illustrations by hand. His assistant would receive these sketches to look over, but the photographers and freelance writers were often given little or no direction at all besides to come up with something new and unusual. When the photographs for the issue arrived, he would pick the most visually interesting and have a variety of sizes of reproductions made on a photostat machine. From these, each spread would be made one at a time, then arranged among the others to create a well-paced magazine. His style for the magazine was radically different than any of its contemporaries. Brodovitch wanted his spreads to be innovative and fresh. While other fashion magazines thought it important to show the whole garment, Brodovitch would crop images unexpectedly or off-center to bring a new dynamism to the layout. He used forms in the photographs or illustrations as a cue for how to handle the shape of the text. In his earlier layouts, he would arrange photographs like playing cards, splayed out on the page or in the shape of a fan. Later in his career, however, he abandoned this technique in favor of using only one or two images to a page. Surrealism found its way onto the pages of the magazines in various experimental forms. For example, Brodovitch once used fashion photographs sent via radio from Paris to New York in blurry forms to communicate this new way of sharing information. Designs also included torn edges on photographs, or pages made to look as they had been torn through with a woman's figure stepping out of them. The motif of isolated body parts, another common Surrealist theme, could be seen on the covers and spreads of Harper's in the form of lips, hands, and eyes. Brodovitch was sensitive to the fact that color was relatively new in magazines, with laborious preparation and high costs. By using process or second color inventively, Brodovitch was able to give the magazine an added sense of currency and luxury. He applied color to his layouts expressively, often choosing to use colors bolder than might be seen in the real world. Even after full-color reproduction became standard practice, he still used broad swaths of single colors for bold emphasis. In terms of photography, Brodovitch had a distinct feel for what the magazine needed. He favored on-location fashion photography as opposed to the studio shots normally used in other fashion publications. He urged his photographers to look for jarring juxtapositions in their images. One such spread features a woman in a full-length Christian Dior gown posed between two circus elephants. (Possible inspiration for Richard Avedon's famous "Dovima with elephants"photo). The cinematic effect, a trademark characteristic of his layouts, involved using photographs as if they were stills from a film. He would repeat a pose or a dress several times across a spread to give a narrative, temporal feeling. At times, Brodovitch would arbitrarily take a series of photographs and adopt a story line to go with them, as though recapping a movie. He was known to push this idea even further by adding film sprocket borders to photographs at times.  Brodovitch also often emphasized spatial illusions, using type and photographs to create multiple perspectives within a space. The notion of mirroring and doubling also interested him, as can be seen in how he paired similar pictures on a spread or dividing halves of one image across the gutter of the page. With this goal of story-telling, Harper's Bazaar can be seen as an example of a mediascape, in that Brodovitch was trying to construct a reality for the imaginations of the readers. He would create versions of small movie stills or spreads in which women were supposed to see themselves rather than the model. For example, he would often use a model's silhouette rather than her whole form, or keep her face in shadow, so that any reader could place themselves in those fashions, leading a charmed life. The result would be a magazine of images "out of which scripts can be formed of imagined lives." He'd go through the stuff fast, really fast, and pick out always the right thing, you know, and then he would mark it up [for copying], an inch, inch and a half, two and a half inches ... But anyhow, I'd go back to see him, he'd have these dam[n] 'stats all over the floor, ankle deep in them, and he would look around, pick one up, until there were six or eight or ten and then he'd lay them out and it worked ... that was the magic of it, you know? In 1949, Brodovitch collaborated with Frank Zachary, and George S. Rosenthal whose family owned a printing company dedicated to mass-market pictorial paperbacks, in the production of the revolutionary publication Portfolio. It has been widely acknowledged as perhaps the definitive graphic design magazine of the twentieth century. The idea for the publication came from Frank Zachary who wanted to put out a magazine that focused solely on art and design, but was at the same time an outstanding example of design itself. Brodovitch was intrigued by the concept. Although he enjoyed his work at Harper's Bazaar, the limitations of space and subject matter often cramped his creative style. Portfolio freed him from the practical and aesthetic restraints to which he had grown accustomed. The pages of the publication were space for his graphic imagination to run wild. With such great capital spent on publicity, Zachary and Rosenthal decided Portfolio would have to include advertising. Upon seeing the advertisements, however, they could not bear to ruin the look and feel of the publication by running them. It was decided that Portfolio would run without the aesthetic burden of advertising, freeing up more space for the overall design. Brodovitch was responsible for sorting through the articles and illustrations to create the spreads. Inside Portfolio, Brodovitch promoted features devoted to respected artists and designers, contributed articles on vernacular design, and made wildly imaginative layouts. The magazine encompassed an array of subject matter and design styles. Works of great French poets were interspersed with off-beat articles about graffiti by hobos. It was a beautifully composed mix-up of all things art. Unfortunately, the publication lasted only three issues. The no-expense-spared ethos of the magazine, paired with the lack of advertising, caused the magazine to quickly fold. Apart from his designing his own magazine, Alexey Vyacheslavovich Brodovitch was also involved in book design in his spare times, such as Observations, a collection of photographs by Richard Avedon and commentary by Truman Capote, both regular contributors to Harper's Bazaar. Although simple and elegant, the layout of the book has an enormous amount of visual variety. Another strong example of Brodovitch's book design is Village Voice columnist Bill Manville's 1960 memoir Saloon Society, The Diary of a Year Beyond Aspirin, which artfully weaves a series of photo collages by David Attie(one of Alexey Vyacheslavovich Brodovitch's student) into and around the text of the book itself. While it has never been published or seen, Brodovitch did the design work for what would have been the very first publication of Truman Capote's novella Breakfast at Tiffany's in Harper's Bazaar. The novella was to appear in the July, 1958 issue. It was to be illustrated with a series of photo montages by David Attie. However, after the publication was scheduled, longtime Harper's editor Carmel Snow, who had wielded considerable influence, was ousted by the magazine's publisher, the Hearst Corporation, and replaced with her niece. Hearst executives then began asking for changes to the novella's tart language. By this time, Attie's montages and Brodovitch's design work had been completed, Capote agreed to change his language partly because of the layouts of the atmospheric photographs. Yet despite Capote's changes, Hearst ordered Harper's not to run the novella anyway concerned that Tiffany's, a major advertiser of the magazine would react negatively to Capote's language. An outraged Capote soon took the work to Esquire, and it appeared in the November 1958 issue with only a single full-page photo of Attie's, despite Capote's urging that more of the work be used. By now Brodovitch was already suffering ill health, and he was plunged into an acute state of depression over the death of his wife, Nina. Over the next two years, Brodovitch was sent to various hospitals on numerous occasions to cure his worsening depression and alcoholism. Throughout these hospital stays, however, Brodovitch had an incessant desire to start new projects. At one point, he began compiling an autobiography, but it was never put together. Brodovitch received a small Minox camera from an old student, Ben Rose, visiting him at Manhattan State Hospital. He slipped the camera in an old box of Pall Mall cigarettes and discreetly began to photograph his fellow patients. Brodovitch would often decide to discharge himself before the treatments had run course. He was so ill, however, that he would be back before the end of the day. With no pension or regular salary from Harper's Bazaar, Brodovitch was faced with mounting hospital bills. He often lost the little freelance work he was able to scrounge up due to his unwillingness to compromise with the clients. Poor health left him unable to show up to the Design Laboratory workshops on a regular basis. One of his students Harvey Lloyd, artist/photographer, took personal care of him and managed his Design Laboratory Workshops during his last six years in NYC to provide him with income to live on. And he said"It was the greatest privilege to do this for him and to learn from him. He loved New York and I had to make him leave to go to his brother in France, as he was wasting away. There will never be another Brodovitch." When Brodovitch stopped coming altogether, a few students halfheartedly tried to keep the class going in his honor. Without its creator, though, the Lab came to an end. In 1966, Brodovitch fell and broke his hip. Physically and financially in a poor state, he moved back to France with his son Nikita to be closer to his many relatives. Two years later, he relocated to Le Thor, a small village even closer to his family in Avignon. He died three years later at age 73. In 1971 the Doctor of Fine Arts Degree was conferred posthumously on Brodovitch by the Philadelphia College of Art. In 1972 the Philadelphia College of Art held the exhibition "Alexey Brodovitch and His Influence" and he was inducted into the Art Directors Club Hall of Fame in New York. In 1982 the exhibition "Hommage à Alexey Brodovitch" was held at Grand-Palais, Paris. In 2002 Phaidon Press published the book Alexey Brodovitch by Kerry William Purcell. Further interest

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|