|

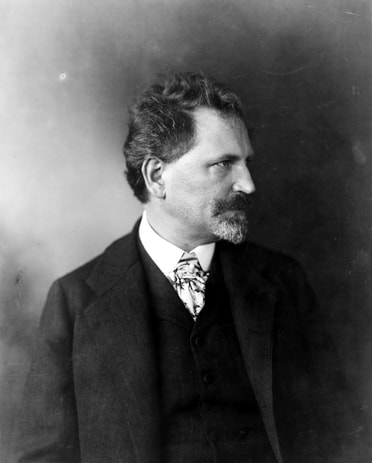

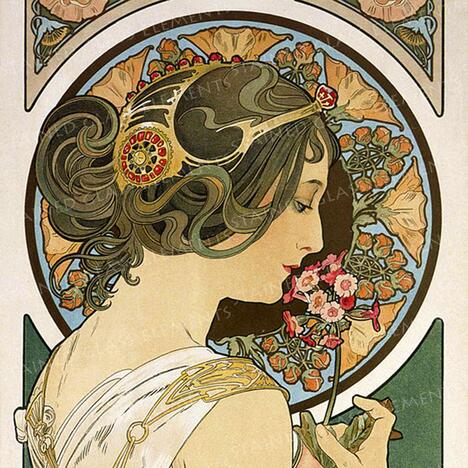

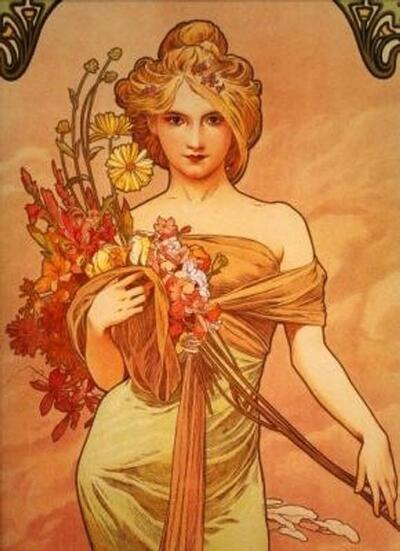

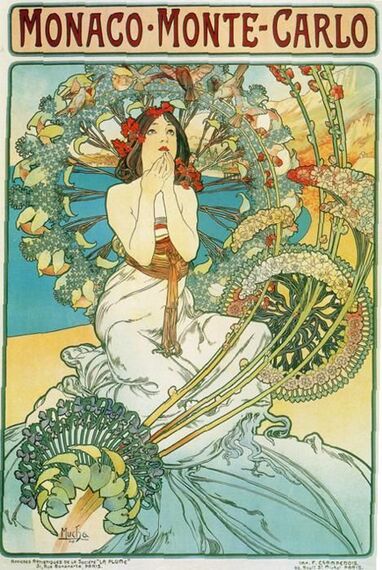

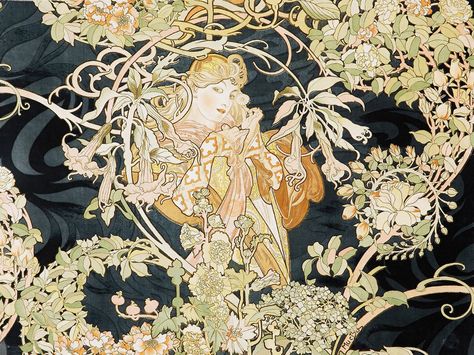

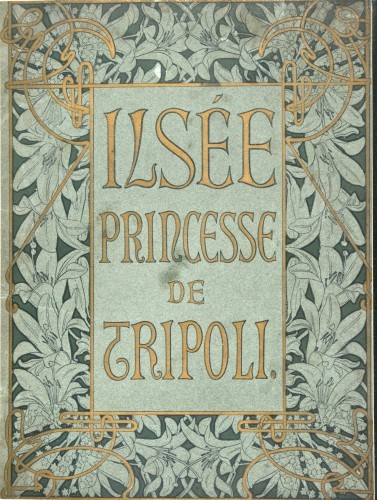

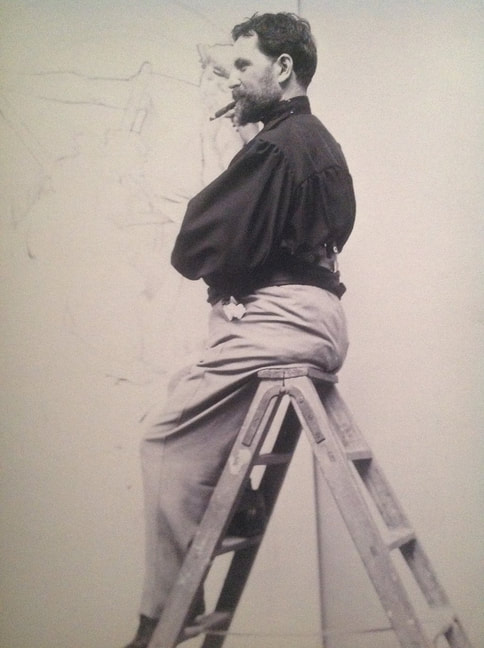

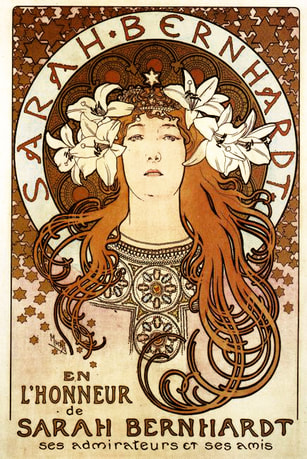

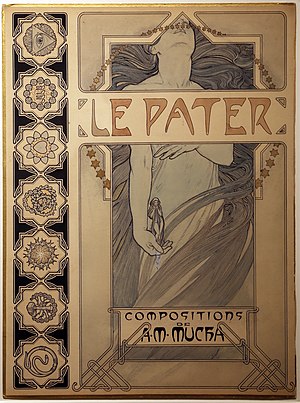

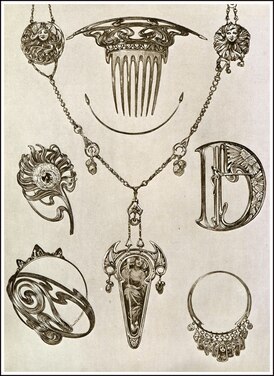

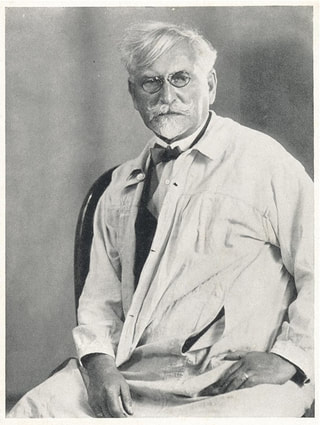

Name: Alphonse Mucha original name: Alfons Maria Mucha birth place: Ivancice, Moravia, Austria Empire birth date: 24 July 1860 zodiac sign: Leo death place: Praque, Czechoslovakia death date: 14 July 1939 Profile of Alphonse Mucha Alfons Maria Mucha (24 July 1860 – 14 July 1939), known internationally as Alphonse Mucha, was a Czech painter, illustrator and graphic artist, living in Paris during the Art Nouveau period, best known for his distinctly stylized and decorative theatrical posters, particularly those of Sarah Bernhardt. He produced illustrations, advertisements, decorative panels, and designs, which became among the best-known images of the period. In the second part of his career, at the age of 43, he returned to his homeland of Bohemia-Moravia region in Austria and devoted himself to painting a series of twenty monumental canvases known as The Slav Epic, depicting the history of all the Slavic peoples of the world, which he painted between 1912 and 1926. In 1928, on the 10th anniversary of the independence of Czechoslovakia, he presented the series to the Czech nation. He considered it his most important work. It is now on display in Brno. Biography of Alphonse Mucha Brno Alphonse Mucha was born on 24 July 1860 in the small town of Ivančice in southern Moravia, then a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, (currently a region of the Czech Republic). His father was a court usher, and his mother was a miller's daughter. Alphonse Mucha showed an early talent for drawing; a local merchant who was impressed by his work provided him free paper, a luxury at time. In 1871, Mucha became a chorister at the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul, Brno, where he received his secondary school education. He became devoutly religious, and wrote later, "For me, the notions of painting, going to church, and music are so closely knit that often I cannot decide whether I like church for its music, or music for its place in the mystery which it accompanies." Mucha grew up in an environment of intense Czech nationalism in all the arts, from music to literature and painting and designed flyers and posters for patriotic rallies. His singing abilities allowed him to continue his musical education at the Gymnázium Brno in the Moravian capital of Brno, but his true ambition was to become an artist. He found some employment designing theatrical scenery and other decorations. In 1878 he applied without success to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, but was rejected and advised "to find a different career". Vienna In 1880, at the age of 19, he traveled to Vienna, the political and cultural capital of the Empire, and found employment as an apprentice scenery painter for a company which made sets for Vienna theaters. While in Vienna, he discovered the museums, churches, palaces and especially theaters, for which he received free tickets from his employer. He also discovered Hans Makart, a very prominent academic painter, who created murals for many of the palaces and government buildings in Vienna, and was a master of portraits and historical paintings in grand format. His style turned Mucha in that artistic direction and influenced his later work. He also began experimenting with photography, which became an important tool in his later work. To his misfortune, a terrible fire in 1881 destroyed the Ringtheater, the major client of his firm. Later in 1881, almost without funds, he took a train as far north as his money would take him. He arrived in Mikulov in southern Moravia, and began making portraits, decorative art and lettering for tombstones. His work was appreciated, and he was commissioned by Count Eduard Khuen Belasi, a local landlord and nobleman, to paint a series of murals for his residence at Emmahof Castle, and then at his ancestral home in the Tyrol, Gandegg Caste. (The paintings at Emmahof were destroyed by fire in 1948, but his early versions in small format exist and are now on display at the museum in Brno.) Mucha showed his skill at mythological themes, the female form, and lush vegetal decoration. Count Belasi, who was also an amateur painter, took Mucha on expeditions to see art in Venice, Florence and Milan, and introduced him to many artists, including the famous Bavarian romantic painter, Wilhelm Kray, who lived in Munich. Munich Count Belasi decided to bring Mucha to Munich for formal training, and paid his tuition and cost of living at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. Mucha moved there in September, 1885. It is not clear how Mucha actually studied at the Munich Academy, but he did become friends with a number of notable Slavic artists there, including the Czechs Karel Vítězslav Mašek, Ludek Marold and the Russian Leonid Pasternak, father of the famous novelist Boris Pasternak. He founded a Czech students' club, and contributed political illustrations to nationalist publications in Prague. In 1886 he received a notable commission for a painting of the Czech patron saints Cyril and Methodius, from a group of Czech emigrants, including some of his relatives, who had founded a Roman Catholic church in the town of Pisek, North Dakota. He was very happy with the artistic environment of Munich: he wrote to friends, "Here I am in my new element, painting. I cross all sorts of currents, but without effort, and even with joy. Here, for the first time, I can find the objectives to reach which used to seem inaccessible." However, he found he could not remain forever in Munich; the Bavarian authorities imposed increasing restrictions upon foreign students and residents. Count Belasi suggested that he travel either to Rome or Paris. With Belasi's financial support, he decided in 1887 to move to Paris. Paris Mucha moved to Paris in 1888 where he enrolled in the Académie Julian and the following year, 1889, Académie Colarossi. The two schools taught a wide variety of different styles. His first professors at the Academie Julien were Jules Lefebvre who specialized in female nudes and allegorical paintings, and Jean-Paul Laurens, whose specialties were historical and religious paintings in a realistic and dramatic style. At the end of 1889, as he approached the age of thirty, his patron, Count Belasi, decided that Mucha had received enough education and ended his subsidies. When he arrived in Paris, Mucha found shelter with the help of the large Slavic community. He lived in a boarding house called the Crémerie at 13 rue de la Grand Chaumerie, whose owner, Charlotte Caron, was famous for sheltering struggling artists; when needed she accepted paintings or drawings in place of rent. Mucha decided to follow the path of another Czech painter he knew from Munich, Ludek Marold, who had made a successful career as an illustrator for magazines. In 1890 and 1891, he began providing illustrations for the weekly magazine La Vie popular, which published novels in weekly segments. His illustration for a novel by Guy de Maupassant, called The Useless Beauty, was on the cover of the 22 May 1890 edition. He also made illustrations for Le Petit Français Illustré, which published stories for young people in both magazine and book form. For this magazine he provided dramatic scenes of battles and other historic events, including a cover illustration of a scene from the Franco-Prussian War which was on the 23 January 1892 edition. His illustrations began to give him a regular income. He was able to buy a harmonium to continue his musical interests and his first camera, which used glass-plate negatives. He took pictures of himself and his friends, and also regularly used it to compose his drawings. He became friends with Paul Gauguin, and shared a studio with him for a time when Gauguin returned from Tahiti in the summer of 1893. In late autumn 1894 he also became friends with the playwright August Strindberg, with whom he had a common interest in philosophy and mysticism. His magazine illustrations led to book illustration; he was commissioned to provide illustrations for Scenes and Episodes of German History by historian Charles Seignobos. Four of his illustrations, including one depicting the death of Frederic Barbarossa, were chosen for display at the 1894 Paris Salon of Artists. He received a medal of honor, his first official recognition. Mucha added another important client in the early 1890s; the Central Library of Fine Arts, which specialized in the publication of books about art, architecture and the decorative arts. It later launched a new magazine in 1897 called Art et Decoration, which played an early and important role in publicizing the Art Nouveau style. He continued to publish illustrations for his other clients, including illustrating a children's book of poetry by Eugène Manuel, and illustrations for a magazine of the theater arts, called La Costume au théâtre. At the end of 1894 his career took a dramatic and unexpected turn when he began to work for French stage actress Sarah Bernhardt. As Mucha later described it, on 26 December 1894 Bernhardt made a telephone call to Maurice de Brunhoff, the manager of the publishing firm Lemercier which printed her theatrical posters, ordering a new poster for the continuation of the play Gismonda. The play, by Victorien Sardou, had already opened with great success on 31 October 1894 at the Théâtre de la Renaissance on the Boulevard Saint-Martin. Bernardt decided to have a poster made to advertise the prolongation of the theatrical run after the Christmas break and insisting it be ready by 1 January 1897. Because of the holidays, none of the regular Lemercier artists were available. When Bernhardt called, Mucha happened to be at the publishing house correcting proofs. He already had experience painting Bernhardt; he had made a series of illustrations of her performing in Cleopatra for Costume au Théâtre in 1890. When Gismonda opened in October 1894, Mucha had been commissioned by the magazine Le Gaulois to make a series of illustrations of Bernhardt in the role for a special Christmas supplement, which was published at Christmas 1894, for the high price of fifty centimes a copy. Brunhoff asked Mucha to quickly design the new poster for Bernhardt. The poster was more than life-size; a little more than two meters high, with Bernhardt in the costume of a Byzantine noblewoman, dressed in an orchid headdress and floral stole, and holding a palm branch in the Easter procession near the end of the play. One of the innovative features of the posters was the ornate rainbow-shaped arch behind the head, almost like a halo, which focused attention on her face; this feature appeared in all of his future theater posters. Probably because of a shortage of time, some areas of the background were left blank instead of his usual decoration. The only background decoration were the Byzantine mosaic tiles behind her head. The poster featured extremely fine draftsmanship and delicate pastel colors, unlike the typical brightly-colored posters of the time. The top of the poster, with the title, was richly composed and ornamented, and balanced the bottom, where the essential information was given in the shortest possible form; just the name of the theater. The poster appeared on the streets of Paris on 1 January 1895 and caused an immediate sensation. Bernhardt was pleased by the reaction; she ordered four thousand copies of the poster in 1895 and 1896, and gave Mucha a six-year contract to produce more. With his posters all over the city, Mucha found himself quite suddenly famous. Following Gismonda, Bernardt switched to a different printer, F. Champenois, who, like Mucha, was put under contract to work for Bernhardt for six years. Champenois had a large printing house on Boulevard Saint Michel which employed three hundred workers, with twenty steam presses. He gave Mucha a generous monthly salary in exchange for the rights to publish all his works. With his increased income, Mucha was able to move to a three-bedroom apartment with a large studio inside a large historic house at 6 rue du Val-de-Grâce originally built by François Mansart. Mucha designed posters for each successive Bernhardt play, beginning with a reprise of one of her early great successes, La Dame aux Camelias (September 1896), followed by Lorenzaccio (1896); Medea (1898); La Tosca (1898) and Hamlet (1899). He sometimes worked from photographs of Bernhardt, as he did for La Tosca. In addition to posters, he designed theatrical programs, sets, costumes, and jewelry for Bernhardt. The enterprising Bernhardt set aside a certain number of printed posters of each play to sell to collectors. The success of the Bernhardt posters brought Mucha commissions for advertising posters. He designed posters for JOB cigarette papers, Ruinart Champagne, Lefèvre-Utile biscuits, Nestlé baby food, Idéal Chocolate, the Beers of the Meuse, Moët-Chandon champagne, Trappestine brandy, and Waverly and Perfect bicycles. With Champenois, he also created a new kind of product, a decorative panel, a poster without text, purely for decoration. They were published in large print runs for a modest price. The first series was The Seasons, published in 1896, depicting four different women in extremely decorative floral settings representing the seasons of the year. In 1897 he produced an individual decorative panel of a young woman in a floral setting, called Reverie, for Champenois. He also designed a calendar with a woman's head surrounded by the signs of the zodiac, The rights were resold to Léon Deschamps, the editor of the arts review La Plume, who brought it out with great success in 1897. The Seasons series was followed by The Flowers The Arts (1898), The Times of Day (1899), Precious Stones (1900), and The Moon and the Stars (1902).Between 1896 and 1904 Mucha created over one hundred poster designs for Champenois. These were sold in various formats, ranging from expensive versions printed on Japanese paper or vellum, to less expensive versions which combined multiple images, to calendars and postcards. His posters focused almost entirely on beautiful women in lavish settings with their hair usually curling in arabesque forms and filling the frame. His poster for the railway line between Paris and Monaco-Monte-Carlo (1897) did not show a train or any identifiable scene of Monaco or Monte-Carlo; it showed a beautiful young woman in a kind of reverie, surrounded by swirling floral images, which suggested the turning wheels of a train. The fame of his posters led to success in the art world; he was invited by Deschamps to show his work in the Salon des Cent exhibition in 1896, and then, in 1897, to have a major retrospective in the same gallery showing 448 works. The magazine La Plume made a special edition devoted to his work, and his exhibition traveled to Vienna, Prague, Munich, Brussels, London, and New York, giving him an international reputation "I had not found any real satisfaction in my old kind of work. I saw that my way was to be found elsewhere, little bit higher. I sought a way to spread the light which reached further into even the darkest corners. I didn't have to look for very long. The Pater Noster (Lord's Prayer): why not give the words a pictorial expression?" Alphonse Mucha made a considerable income from his theatrical and advertising work, but he wished even more to be recognized as a serious artist and philosopher. He was a devoted Catholic, but also was interested in mysticism. Le Pater was published on 20 December 1899, only 510 copies were printed. The original watercolor paintings of the page were displayed in the Austrian pavilion at the 1900 Exposition. He considered Le Pater to be his printed masterpiece, and referred to it in the New York Sun of 5 January 1900 as a work into which he had "put his soul". In 1899 Alphonse Mucha also collaborated with the jeweler Georges Fouquet to make a bracelet for Sarah Bernhardt in the form of a serpent, made of gold and enamel, similar to the costume jewelry Bernhardt wore in Medea. The Cascade pendant designed for Fouquet by Mucha (1900) is in the form of a waterfall. After the 1900 Exposition, Fouquet decided to open a new shop and asked Mucha to design the interior. The centerpieces of the design were two peacocks, the traditional symbol of luxury, made of bronze and wood with colored glass decoration. To the side was a shell-shaped fountain, with three gargoyles spouting water into basins, surrounding the statue of a nude woman. The salon was further decorated with carved moldings and stained glass, thin columents with vegetal designs, and a ceiling with molded floral and vegetal elements. It marked a summit of Art Nouveau decoration. (The Salon opened in 1901, just as tastes were beginning to change, moving away from Art Nouveau to more naturalistic patterns. It was taken apart in 1923, and a replaced by a more traditional shop design. Fortunately most of the original decoration was preserved, and was donated in 1914 and 1949 to the Carnavalet Museum in Paris, where it can be seen today.) 1900, Universal Exposition, Paris The Paris Universal Exposition of 1900, famous as the first grand showcase of the Art Nouveau, gave Mucha an opportunity to move in an entirely different direction, toward the large-scale historical paintings which he had admired in Vienna. It also allowed him to express his Czech patriotism. His work appeared in many forms at the Exposition. He designed the posters, menus, displays for the jeweler and perfume maker, with statuettes and panels of women depicting the scents of rose, orange blossom, violet and buttercup. His more serious art works, including his drawings for Le Pater, were shown in the Austrian Pavilion and in the Austrian section of the Grand Palais. His work at the Exposition earned him the title of Knight of the Order of Franz Joseph I from the Austrian government, the Legion of Honor from the French Government. During the course of the Exposition, Mucha proposed another unusual project. The Government of France planned to take down the Eiffel Tower, built especially for the Exposition, as soon as the Exposition ended. Mucha proposed that, after the Exposition, the top of the tower should be replaced by a sculptural monument to humanity be constructed on the pedestal. The tower proved to be popular with both tourists and Parisians, and the Eiffel Tower remained after the Exhibit ended. Mucha's next project was a series of seventy-two printed plates of watercolors of designs, titled Documents Decoratifs, which were published in 1902 by the Librarie central des beaux-arts. They represented ways that floral, vegetal and natural forms could be used in decoration and decorative objects, featuring plates of elaborate jewel designs for brooches and other pieces, with swirling arabesques and vegetal forms, with incrustations of enamel and colored stones. "You must have been very surprised by my decision to come to America, perhaps even amazed. But in fact I had been preparing to come here for some time. It had become clear to me that that I would never have time to do the things I wanted to do if I did not get away from the treadmill of Paris, I would be constantly bound to publishers and their whims...in America, I don't expect to find wealth, comfort, or fame for myself, only the opportunity to do some more useful work." In March 1904 Mucha sailed for New York with letters of introduction from Baroness Salomon de Rothschild. He intended to find funding for his grand project, The Slav Epic, which he had conceived during the 1900 Exposition. At one Pan-Slavic banquet in New York City, he met Charles Richard Crane, a wealthy businessman and philanthropist, who was a passionate Slavophile and became Mucha's most important patron. He made a few trips to USA between 1904 and 1910, usually staying for five to six months. In 1906, he returned to New York with his new wife, (Marie/Maria) Chytilová, and they remained in the U.S. until 1909 and their first child, Jaroslava, was born in New York in 1909. His principal income in the United States came from teaching, and artistically, the trip was not a success; His finest work in America is often considered to be his portrait of Josephine Crane Bradley, the daughter of his patron, in the character of Slavia, in Slavic costume and surrounded by symbols from Slavic folklore and art. During his long stay in Paris, Mucha had never given up his dream of being a history painter, and to illustrate accomplishments of the Slavic peoples of Europe. He made the decision to return to his old country, still then part of the Austrian Empire. His first project in 1910 was the decoration of the reception room of the mayor of Prague. He designed and created a series of large-scale murals for the domed ceiling and walls with athletic figures in heroic poses, depicting the contributions of Slavs to European history over the centuries, and the theme of Slavic unity. These paintings on the ceiling and walls were in sharp contrast to his Parisian work, and were designed to send a patriotic message. The Lord Mayor's Hall was finished in 1911, and Mucha was able to devote his attention to what he considered his most important work; The Slav Epic, a series of large painting illustrating the achievements of the Slavic peoples over history. The series had twenty paintings, half devoted to the history of the Czechs, and ten to other Slavic peoples. The canvases were enormous; the finished works measured six by eight meters. He created the twenty canvases between 1912 and 1926. He worked throughout the First World War, when the Austrian Empire was at war with France, despite wartime restrictions, which made canvas hard to obtain. He continued his work after the war ended, when the new Republic of Czechoslovkia was created. The cycle was completed in 1928 in time for the tenth anniversary of the proclamation of the Czechoslovak Republic In the political turmoil of the 1930s, Mucha's work received little attention in Czechoslovakia. However, in 1936 a major retrospective was held in Paris at the Jeu de Paume museum, with 139 works, including three canvases from the Slav Epic. Hitler and Nazi Germany began to threaten Czechoslovakia in the 1930s. Mucha began work on a new series, a triptych depicting the Age of Reason, the Age of Wisdom and the Age of Love, which he worked on from 1936 to 1938, but never completed. On 15 March 1939, the German army paraded through Prague, and Hitler, at Prague castle, declared lands of the former Czechoslovakia to be part of the Greater German Reich as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Mucha's role as a Slav nationalist and Freemason made him a prime target. He was arrested, interrogated for several days, and released. By then his health was broken. He contracted pneumonia and died on 14 July 1939, a few weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War. Though public gatherings were banned, a huge crowd attended his interment in the Slavín Monument of Vyšehrad cemetery, reserved for notable figures in Czech culture.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|