|

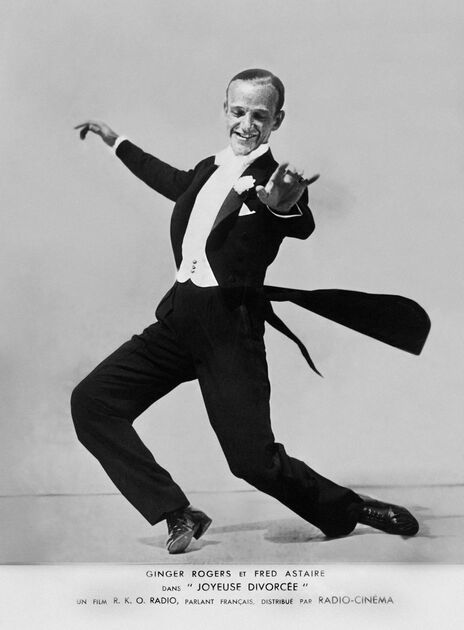

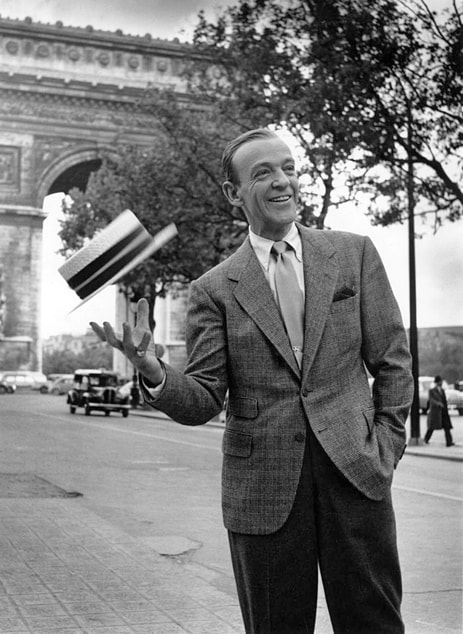

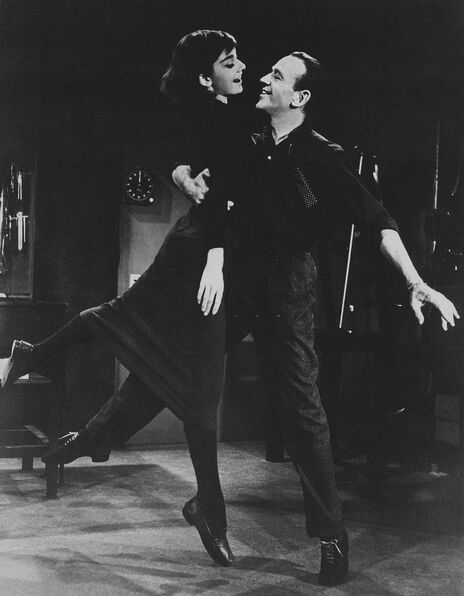

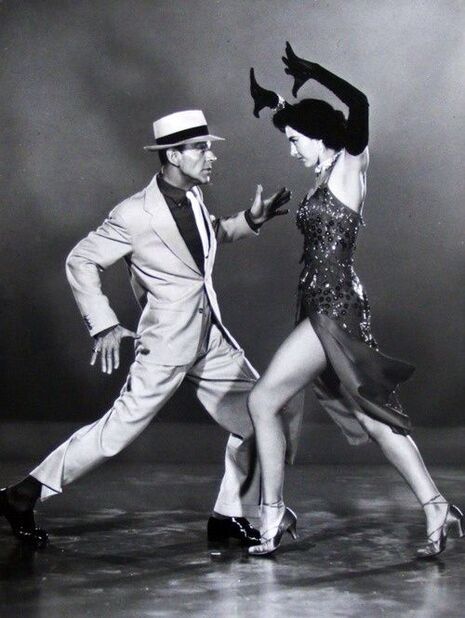

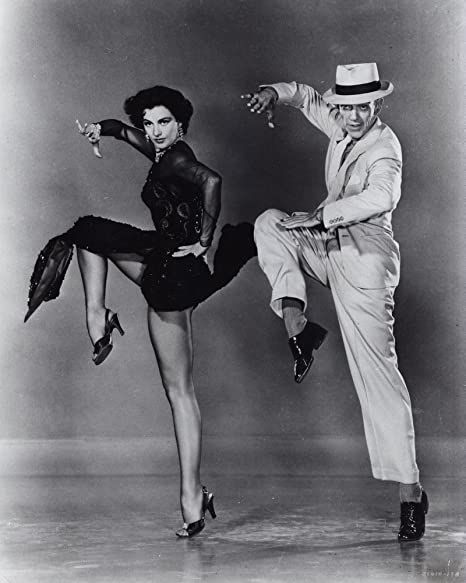

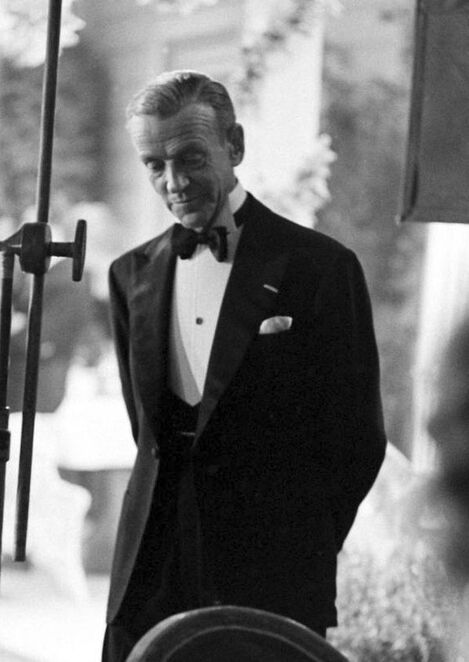

Fred Astaire (born Frederick Austerlitz; May 10, 1899 – June 22, 1987) was an American actor, dancer, singer, choreographer, and television presenter. He is widely considered the greatest dancer in film history. His stage and subsequent film and television careers spanned a total of 76 years. He starred in more than 10 Broadway and West End musicals, made 31 musical films, four television specials, and numerous recordings. As a dancer, his outstanding traits were an uncanny sense of rhythm, perfectionism, and innovation. His most memorable dancing partnership was with Ginger Rogers, with whom he co-starred in a series of ten Hollywood musicals during the age of Classical Hollywood cinema, including Top Hat (1935), Swing Time (1936), and Shall We Dance (1937). Among the other notable films in which Astaire gained further popularity and took the genre of tap dancing to a new level were Holiday Inn (1942), Easter Parade (1948), The Band Wagon (1953), Funny Face (1957), and Silk Stockings (1957). The American Film Institute named Astaire the fifth-greatest male star of Classic Hollywood cinema in 100 Years... 100 Stars. BiographyFred Astaire was born Frederick Austerlitz on May 10, 1899, in Omaha, Nebraska, the son of Johanna "Ann" (née Geilus; 1878–1975) and Friedrich "Fritz" Emanuel Austerlitz, later Frederic Austerlitz (1868–1923). Astaire's mother's family was originally from East Prussia and Alsace. Astaire's father was born in Linz, Austria to Roman Catholic parents who had converted from Judaism. Astaire's father, Fritz Austerlitz, arrived in New York City at the age of 25 and moved to Omaha, Nebraska, where he was employed by the Storz Brewing Company. Astaire's mother dreamed of escaping Omaha by her children's talents. Astaire's older sister, Adele, was an instinctive dancer and singer early in her childhood. Johanna planned a "brother and sister act", common in vaudeville at the time, for her two children. Although Fred refused dance lessons at first, he easily mimicked his older sister's steps and took up piano, accordion, and clarinet When their father lost his job, the family moved to New York City in January 1905 to launch the show business careers of the children. They began training at the Alviene Master School of the Theatre and Academy of Cultural Arts. Fred and Adele's mother suggested they change their name to "Astaire," as she felt "Austerlitz" was reminiscent of the Battle of Austerlitz. Family legend attributes the name to an uncle surnamed "L'Astaire." They were taught dance, speaking, and singing in preparation for developing an act. Their first act was called Juvenile Artists Presenting an Electric Musical Toe-Dancing Novelty. In November 1905, the goofy act debuted in Keyport, New Jersey at a "tryout theater." The local paper wrote, "the Astaires are the greatest child act in vaudeville. As a result of their father's salesmanship, Fred and Adele landed a major contract and played the Orpheum Circuit in the Midwest, Western and some Southern cities in the US. Soon Adele grew to at least three inches taller than Fred, and the pair began to look incongruous. The family decided to take a two-year break from show business to let time take its course and to avoid trouble from the Gerry Society and the child labor laws of the time. The career of the Astaire siblings resumed with mixed fortunes, though with increasing skill and polish, as they began to incorporate tap dancing into their routines. Astaire's dancing was inspired by Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and John "Bubbles" Sublett. From vaudeville dancer Aurelio Coccia, they learned the tango, waltz, and other ballroom dances popularized by Vernon and Irene Castle. By age 14, Fred had taken on the musical responsibilities for their act. He first met George Gershwin, who was working as a song plugger for Jerome H. Remick's music publishing company, in 1916. Their chance meeting was to affect the careers of both artists profoundly. Astaire was always on the lookout for new steps on the circuit and was starting to demonstrate his ceaseless quest for novelty and perfection. The Astaires broke into Broadway in 1917 with Over the Top, a patriotic revue, and performed for U.S. and Allied troops at this time as well. They followed up with several more shows. Adele's sparkle and humor drew much of the attention, owing in part to Fred's careful preparation and sharp supporting choreography. She still set the tone of their act. But by this time, Astaire's dancing skill was beginning to outshine his sister's. During the 1920s, Fred and Adele appeared on Broadway and the London stage. They won popular acclaim with the theater crowd on both sides of the Atlantic in shows such as Jerome Kern's The Bunch and Judy (1922), George and Ira Gershwin's Lady, Be Good (1924), Funny Face (1927) and later in The Band Wagon (1931). Astaire's tap dancing was recognized by then as among the best. For example, Robert Benchley wrote in 1930, "I don't think that I will plunge the nation into war by stating that Fred is the greatest tap-dancer in the world." Whilst in London, Fred studied piano at the Guildhall School of Music alongside his friend and colleague Noël Coward. After the close of Funny Face, the Astaires went to Hollywood for a screen test at Paramount Pictures, but Paramount deemed them unsuitable for films. They split in 1932 when Adele married her first husband, Lord Charles Cavendish, the second son of the 9th Duke of Devonshire. In 1933, Fred Astaire married 25-year-old Phyllis Potter (formerly Phyllis Livingston Baker [1908–1954]), a Boston-born New York socialite and former wife of Eliphalet Nott Potter III (1906–1981), despite his mother's and sister's objections. After the end of the partnership with his sister, Fred Astaire went on to achieve success on his own on Broadway and in London with Gay Divorce (later made into the film The Gay Divorcee) while considering offers from Hollywood. Then after a screen test with RKO, Fred Astaire got a contract. David O. Selznick, who had signed Astaire to RKO and commissioned the test, stated in a memo, "I am uncertain about the man, but I feel, in spite of his enormous ears and bad chin line, that his charm is so tremendous that it comes through even on this wretched test." According to Hollywood folklore, a screen test report on Astaire for RKO Radio Pictures, now lost along with the test, is reported to have read: "Can't sing. Can't act. Balding. Can dance a little." Astaire later clarified, insisting that the report had read: "Can't act. Slightly bald. Also dances." RKO lent Astaire for a few days to MGM in 1933 for his significant Hollywood debut in the successful musical film Dancing Lady. In the movie, he appeared as himself dancing with Joan Crawford. On his return to RKO, he got fifth billing after fourth billed Ginger Rogers in the 1933 Dolores del Río vehicle Flying Down to Rio. In a review, Variety magazine attributed its massive success to Astaire's presence: The main point of Flying Down to Rio is the screen promise of Fred Astaire ... He's assuredly a bet after this one, for he's distinctly likable on the screen, the mike is kind to his voice and as a dancer, he remains in a class by himself. The latter observation will be no news to the profession, which has long admitted that Astaire starts dancing where the others stop hoofing. When the idea of partnering with Ginger Rogers was brought to Fred Astaire, he was initially very reluctant. He wrote his agent, "I don't mind making another picture with her, but as for this 'team' idea, it's 'out!' I've just managed to live down one partnership and I don't want to be bothered with anymore." However, he was persuaded by the apparent public appeal of the Astaire-Rogers pairing. The partnership, and the choreography of Astaire and Hermes Pan, helped make dancing an important element of the Hollywood film musical. Astaire and Rogers made nine films together at RKO. These included The Gay Divorcee (1934), Roberta (1935), Top Hat (1935), Follow the Fleet (1936), Swing Time (1936), Shall We Dance (1937), and Carefree (1938). Six out of the nine Astaire–Rogers musicals became the biggest moneymakers for RKO; Astaire received a percentage of the films' profits, something scarce in actors' contracts at that time. Despite their success, Astaire was unwilling to have his career tied exclusively to any partnership. He negotiated with RKO to strike out on his own with A Damsel in Distress in 1937 with an inexperienced, non-dancing Joan Fontaine, unsuccessfully as it turned out. He returned to make two more films with Rogers, Carefree (1938) and The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939). While both films earned respectable gross incomes, they both lost money because of increased production costs, and Astaire left RKO, after being labeled "box office poison" by the Independent Theatre Owners of America. Astaire was reunited with Rogers in 1949 at MGM for their final outing, The Barkleys of Broadway, the only one of their films together to be shot in Technicolor. Their partnership elevated them both to stardom, and all of the films brought a certain prestige and artistry that all studios coveted at the time. as Katharine Hepburn reportedly said, "He gives her class and she gives him sex appeal." According to Astaire, "Ginger had never danced with a partner before Flying Down to Rio. She faked it an awful lot. She couldn't tap and she couldn't do this and that ... but Ginger had style and talent and improved as she went along. She got so that after a while everyone else who danced with me looked wrong." In 1976, British talk-show host Sir Michael Parkinson asked Astaire who his favorite dancing partner was on Parkinson. At first, Astaire refused to answer. But, ultimately, he said "Excuse me, I must say Ginger was certainly, uh, uh, the one. You know, the most effective partner I had. Everyone knows. Astaire left RKO in 1939 to freelance and pursue new film opportunities, with mixed though generally successful outcomes. Throughout this period, Astaire continued to value the input of choreographic collaborators. Unlike the 1930s when he worked almost exclusively with Hermes Pan, he tapped the talents of other choreographers to innovate continually. His first post-Ginger dance partner was the redoubtable Eleanor Powell, considered the most exceptional female tap-dancer of her generation. They starred in Broadway Melody of 1940, in which they performed a celebrated extended dance routine to Cole Porter's "Begin the Beguine." In his autobiography Steps in Time, Astaire remarked, "She 'put 'em down' like a man, no ricky-ticky-sissy stuff with Ellie. She really knocked out a tap dance in a class by herself." He played alongside Bing Crosby in Holiday Inn (1942) and later Blue Skies (1946). But, in spite of the enormous financial success of both, he was reportedly dissatisfied with roles where he lost the girl to Crosby. The former film is memorable for his virtuoso solo dance to "Let's Say it with Firecrackers". The latter film featured "Puttin' On the Ritz", an innovative song-and-dance routine indelibly associated with him. Other partners during this period included Paulette Goddard in Second Chorus (1940), in which he dance-conducted the Artie Shaw orchestra. He made two pictures with Rita Hayworth. The first film, You'll Never Get Rich (1941), catapulted Hayworth to stardom. In the movie, Astaire integrated for the third time Latin American dance idioms into his style. His second film with Hayworth, You Were Never Lovelier (1942), was equally successful. It featured a duet to Kern's "I'm Old Fashioned," which became the centerpiece of Jerome Robbins's 1983 New York City Ballet tribute to Astaire. He next appeared opposite the seventeen-year-old Joan Leslie in the wartime drama The Sky's the Limit (1943). In it, he introduced Arlen and Mercer's "One for My Baby" while dancing on a bar counter in a dark and troubled routine. Astaire choreographed this film alone and achieved modest box office success. It represented a notable departure for Astaire from his usual charming, happy-go-lucky screen persona, and confused contemporary critics. His next partner, Lucille Bremer, was featured in two lavish vehicles, both directed by Vincente Minnelli. The fantasy Yolanda and the Thief (1945) featured an avant-garde surrealistic ballet. In the musical revue Ziegfeld Follies (1945), Astaire danced with Gene Kelly to the Gershwin song "The Babbit and the Bromide," a song Astaire had introduced with his sister Adele back in 1927. Always insecure and believing his career was beginning to falter, Astaire surprised his audiences by announcing his retirement during the production of his next film Blue Skies (1946). He nominated "Puttin' on the Ritz" as his farewell dance. After announcing his retirement in 1946, Astaire concentrated on his horse-racing interests and in 1947 founded the Fred Astaire Dance Studios, which he subsequently sold in 1966. Astaire's retirement did not last long. Astaire returned to the big screen to replace an injured Kelly in Easter Parade (1948) opposite Judy Garland, Ann Miller, and Peter Lawford. He followed up with a final reunion with Rogers (replacing Judy Garland) in The Barkleys of Broadway (1949). Both of these films revived Astaire's popularity and in 1950 he starred in more musicals including Three Little Words with Vera-Ellen, Royal Wedding (1951) with Jane Powell and Peter Lawford, The Belle of New York (1952) with Vera-Ellen, The Band Wagon (1953). Soon after, Astaire, like the other remaining stars at MGM, was let go from his contract because of the advent of television and the downsizing of film production. In 1954, Astaire was about to start work on a new musical, Daddy Long Legs (1955) with Leslie Caron at 20th Century Fox. Then, his wife Phyllis became ill and suddenly died of lung cancer at the age of 46, ending their twenty-one years of blissful marriage and left Astaire devastated. He wanted to shut down the picture and offered to pay the production costs out of his pocket. However, Johnny Mercer, the film's composer and Fox studio executives convinced him that work would be the best thing for him. Daddy Long Legs only did moderately well at the box office. His next film for Paramount, Funny Face (1957), teamed him with Audrey Hepburn and Kay Thompson. Despite the sumptuousness of the production and the good reviews from critics, it failed to make back its cost. Similarly, Astaire's next project – his final musical at MGM, Silk Stockings (1957), in which he co-starred with Cyd Charisse, also lost money at the box office. The music for "Dancing in the dark" in film Silk Stockings(1957) Afterward, Astaire announced that he was retiring from dancing in the film. His legacy at this point was 30 musical films in 25 years. Astaire did not retire from dancing altogether. He made a series of four highly-rated Emmy Award-winning musical specials for television in 1958, 1959, 1960, and 1968. Each featured Barrie Chase, with whom Astaire enjoyed a renewed period of dance creativity. The first of these programs, 1958's An Evening with Fred Astaire, won nine Emmy Awards, including "Best Single Performance by an Actor" and "Most Outstanding Single Program of the Year." It was also noteworthy for being the first major broadcast to be prerecorded on color videotape. Astaire won the Emmy for Best Single Performance by an Actor. Astaire played Julian Osborne, a non-dancing character, in the nuclear war drama On the Beach (1959). He was nominated for a Golden Globe Best Supporting Actor award for his performance. Astaire appeared in non-dancing roles in three other films and several television series from 1957 to 1969. Astaire's last major musical film was Finian's Rainbow (1968), directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Astaire shed his white tie and tails to play an Irish rogue who believes that if he buries a crock of gold in the shadows of Fort Knox the gold will multiply. Astaire's dance partner was Petula Clark, who played his character's skeptical daughter. Astaire continued to act in the 1970s. In the movie The Towering Inferno (1974), he danced with Jennifer Jones and received his only Academy Award nomination, in the category of Best Supporting Actor. Astaire also appeared in the first two That's Entertainment! documentaries, in the mid-1970s. In the second compilation, aged seventy-six, he performed brief dance linking sequences with Kelly, his last dance performances in a musical film. In 1979, He made a well publicized guest appearance on the science-fiction television series Battlestar Galactica, because of his grandchildren's interest in the series and the producers created an entire episode to feature him. This episode marked the final time that he danced on screen. His final film was the 1981 adaptation of Peter Straub's novel Ghost Story. This horror film was also the last for two of his most prominent castmates, Melvyn Douglas and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Astaire revolutionized dance on film by having complete autonomy over its presentation. He is credited with two important innovations in early film musicals. First, he insisted that a closely tracking dolly camera film a dance routine in as few shots as possible, typically with just four to eight cuts, while holding the dancers in full view at all times. This gave the illusion of an almost stationary camera filming an entire dance in a single shot. Astaire's style of dance sequences allowed the viewer to follow the dancers and choreography in their entirety. Astaire maintained this policy from The Gay Divorcee in 1934 until his last film musical Finian's Rainbow in 1968, when director Francis Ford Coppola overruled him. Astaire's second innovation involved the context of the dance; he was adamant that all song and dance routines be integral to the plotlines of the film. Instead of using dance as a spectacle as Busby Berkeley did, Astaire used it to move the plot along. Typically, an Astaire picture would include at least three standard dances. One would be a solo performance by Astaire, which he termed his "sock solo." Another would be a partnered comedy dance routine. Finally, he would include a partnered romantic dance routine. Although Astaire was the primary choreographer of all his dance routines, he welcomed the input of collaborators and notably his principal collaborator Hermes Pan. Occasionally Astaire took joint screen credit for choreography or dance direction, but he usually left the screen credit to his collaborator. This can lead to the completely misleading impression that Astaire merely performed the choreography of others. Later in life, he admitted, "I had to do most of it myself." Astaire was a virtuoso dancer, able when called for to convey light-hearted venturesomeness or deep emotion. His technical control and sense of rhythm were astonishing. Long after the photography for the solo dance number "I Want to Be a Dancin' Man" was completed for the 1952 feature The Belle of New York, it was decided that Astaire's humble costume and the threadbare stage set were inadequate and the entire sequence was reshot. The 1994 documentary That's Entertainment! III shows the two performances side by side in split-screen. Frame for frame, the two performances are identical, down to the subtlest gesture. Astaire's execution of a dance routine was prized for its elegance, grace, originality, and precision. He drew from a variety of influences, including tap and other black rhythms, classical dance, and the elevated style of Vernon and Irene Castle. His was a uniquely recognizable dance style that greatly influenced the American Smooth style of ballroom dance and set standards against which subsequent film dance musicals would be judged. He termed his eclectic approach "outlaw style," an unpredictable and instinctive blending of personal artistry. His dances are economical yet endlessly nuanced. As Jerome Robbins stated, "Astaire's dancing looks so simple, so disarming, so easy, yet the understructure, the way he sets the steps on, over or against the music, is so surprising and inventive." According to Astaire himself: “Working out the steps is a very complicated process—something like writing music. You have to think of some step that flows into the next one, and the whole dance must have an integrated pattern. If the dance is right, there shouldn't be a single superfluous movement. It should build to a climax and stop!” His perfectionism was legendary, but his relentless insistence on rehearsals and retakes was a burden to some. When time approached for the shooting of a number, Astaire would rehearse for another two weeks and record the singing and music. With all the preparation completed, the actual shooting would go quickly, conserving costs. Astaire agonized during the process, frequently asking colleagues for acceptance for his work. As Vincente Minnelli stated, "He lacks confidence to the most enormous degree of all the people in the world. He will not even go to see his rushes... He always thinks he is no good." Although he viewed himself primarily as an entertainer, his artistry won him the admiration of twentieth-century dancers such as Gene Kelly, George Balanchine, the Nicholas Brothers, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Margot Fonteyn, Bob Fosse, Gregory Hines, Rudolf Nureyev, Michael Jackson, and Bill Robinson. Balanchine compared him to Bach, describing him as "the most interesting, the most inventive, the most elegant dancer of our times," while for Baryshnikov he was "a genius... a classical dancer like I never saw in my life." "No dancer can watch Fred Astaire and not know that we all should have been in another business," he concluded. Always immaculately turned out, he and Cary Grant were called "the best-dressed actor[s] in American movies." Astaire remained a male fashion icon even into his later years, eschewing his trademark top hat, white tie, and tails, which he hated. Instead, he favored a breezy casual style of tailored sport jackets, colored shirts, and slacks—the latter usually held up by the distinctive use of an old tie or silk scarf in place of a belt. Intensely private, Fred Astaire was rarely seen on the Hollywood social scene. Instead, he devoted his spare time to his family and his hobbies, which included horse racing, playing the drums, songwriting, and golfing. In 1946, his horse Triplicate won the Hollywood Gold Cup and San Juan Capistrano Handicap. He remained physically active well into his eighties. He took up skateboarding in his late seventies and was awarded a life membership in the National Skateboard Society. At seventy-eight, he broke his left wrist while skateboarding in his driveway. He also had an interest in boxing and true crime. He was good friends with David Niven, Randolph Scott, Clark Gable and Gregory Peck. Niven described him as "a pixie—timid, always warm-hearted, with a penchant for schoolboy jokes." On June 24, 1980, at the age of 81, he married a second time. Robyn Smith was 45 years his junior and a jockey who rode for Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt Jr. (she also dated Vanderbilt in the 1970s), and appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated on July 31, 1972. Astaire's life has never been portrayed on film. He always refused permission for such portrayals, saying, "However much they offer me—and offers come in all the time—I shall not sell." Astaire's will included a clause requesting that no such portrayal ever take place; he commented, "It is there because I have no particular desire to have my life misinterpreted, which it would be." On December 5, 2021, Tom Holland announced that he would be portraying Fred Astaire in an upcoming biopic, which attracted criticism due to the clause. Fred Astaire died of pneumonia on June 22, 1987, at the age of 88. His body was buried at Oakwood Memorial Park Cemetery in Chatsworth, California. One of his last requests was to thank his fans for their years of support.

In addition to Phyllis Potter's son, Eliphalet IV (known as Peter), the Astaires had two children. The Astaires' son Fred Jr. (1936– ), appeared with his father in the movie Midas Run and later became a charter pilot and rancher. The Astaires' daughter Ava Astaire (1942– ) remains involved in promoting her father's legacy.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|