|

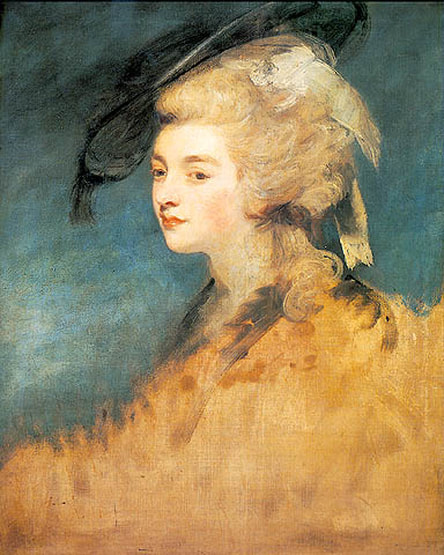

Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (née Spencer; 7 June 1757 – 30 March 1806), was an English socialite, political organiser, style icon, author, and activist. Of noble birth from the Spencer family, married into the Cavendish family, she was the first wife of William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, and the mother of the 6th Duke of Devonshire. As the Duchess of Devonshire, she garnered much attention and fame in society during her lifetime. With a pre-eminent position in the peerage of England, the duchess was famous for her charisma, political influence, beauty, unusual marital arrangement, love affairs, socializing, and gambling. She was the great-great-great-great aunt of Diana, Princess of Wales. Their lives, centuries apart, have been compared in tragedy. BiographyThe Duchess was born Miss Georgiana Spencer, on 7 June 1757, as the first child of John Spencer (great-grandson of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, and later Earl Spencer) and his wife, Georgiana (née Poyntz, later Countess Spencer), at the Spencer family home, Althorp. After her daughter's birth, her mother Lady Spencer wrote that "I will own I feel so partial to my Dear little Gee, that I think I never shall love another so well." Two younger siblings followed: Henrietta ("Harriet") and George. (The daughter of her sister Henrietta, Lady Caroline Lamb, would become a writer and lover of Lord Byron). When her father assumed the title of Viscount Spencer in 1761, she became The Honourable Georgiana Spencer. In 1765, her father became Earl Spencer, and she Lady Georgiana Spencer. On her seventeenth birthday, 7 June 1774, Lady Georgiana Spencer was married to society's most eligible bachelor, William Cavendish, the 5th Duke of Devonshire (aged 25). The wedding took place at Wimbledon Parish Church. It was a small ceremony. Her parents were emotionally reluctant to let their daughter go, but she was wed to one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in the land. Her father, who had always shown affection to his children, wrote to her, "My Dearest Georgiana, I did not know till lately how much I loved you; I miss you more every day and every hour". Mother and daughter continued to correspond throughout their lives, and many of their letters survive. From the beginning of the marriage, the Duke of Devonshire proved to be an emotionally reserved man who was quite unlike the Duchess's father and who did not meet the Duchess' emotional needs. The spouses also had little in common. He would seldom be at her side and would spend nights at Brooks's playing cards. The Duke continued with adulterous behaviours throughout their married life, and discord followed pregnancies that ended in miscarriage or failure to produce a male heir. Before their marriage, the Duke had fathered an illegitimate daughter, Charlotte Williams. This was unknown to the Duchess until years after her marriage to the Duke. After the death of the child's mother, the Duchess was compelled to raise Charlotte herself. The Duchess was "very pleased" with Charlotte, although her own mother Lady Spencer expressed disapproval. In 1782, while on a retreat from London with the Duke, the Duchess met Lady Elizabeth Foster (widely known as "Bess") in the City of Bath, with whom she became close friends. With the Duke's acquiescence, Lady Elizabeth, who had become destitute after separating from her husband and two sons, went to live with The Duke and the Duchess. The Duchess had been desperately lonely since her marriage to the Duke, and finally having found what she believed to be the ideal friend, she became emotionally dependent on Lady Elizabeth. When the Duke began a sexual relationship with Lady Elizabeth, a ménage à trois was established. Having no alternative, the Duchess became complicit in her best friend's affair with her husband the Duke, and it was arranged that Lady Elizabeth live with them permanently. While it was common for male members of the upper class to have mistresses, it was not common or generally acceptable for a mistress to live so openly with a married couple, and the love triangle was a notorious topic. Lady Elizabeth's affair with the Duke resulted in two illegitimate children: a daughter, Caroline Rosalie St Jules, and a son, Augustus Clifford. Lady Elizabeth also engaged in well documented sexual relations with other men while she was in the "love triangle" with the Duke and Duchess. Despite her unhappiness with her detached and philandering husband and volatile marriage, the duchess, as contemporary norms dictated, was not socially permitted to take a lover without producing an heir. The first successful pregnancy resulted in the birth of Lady Georgiana Dorothy Cavendish on 12 July 1783. Called "Little G," she would become the Countess of Carlisle and have her own issue. On 29 August 1785, a second successful pregnancy resulted in another daughter: Lady Harriet Elizabeth Cavendish, called "Harryo," who would become Countess Granville and also have children of her own. Finally, on 21 May 1790, the Duchess gave birth to a male heir to the dukedom: William George Spencer Cavendish, who took the title of Marquess of Hartington at birth, and was called "Hart." He would never marry and became known as "the bachelor duke." The Duchess had developed a strong mothering sentiment since raising Charlotte, and she insisted on nursing her own children (contrary to the aristocratic custom of having a wet nurse). With the birth of the Marquess of Hartington, the Duchess was able to take a lover. In 1791 she became pregnant by her lover Charles Grey (later Earl Grey). Sent off to France, the Duchess believed she would die in childbirth. On 20 February 1792, Eliza Courtney was born without complications to mother and child and Duchess was forced to give away the illegitimate daughter to Charles Grey's family. The Duchess would later be allowed to pay visits to her daughter, providing her with presents and affection. While in exile in France, the Duchess of Devonshire suffered from isolation and felt her separation from her children. To return to England and her children, she conceded to her husband's demands and renounced her love for Charles Grey. From childhood, Georgiana showed a characteristic need to please others and a need for attention. Her mother Lady Spencer, Georgiana Spencer, Countess Spencer raised her to behave as if she were a courtier always on show, and this training only augmented her people pleasing tendencies. Georgiana was generous, charismatic, good-humored, and intelligent. Kindhearted, Georgiana instinctively wanted to help others and from a young age, happily gave her money to poor children or her friends as well as animals. She also lacked the condescending airs of the aristocracy; she made people of all classes feel valued and at ease in her company. Despite being extremely self-conscious and making strenuous effort to appear perfect, Georgiana "always appeared natural, even when she was called upon to open a ball in front of 800 people. She could engage in friendly chatter with several people simultaneously" and still made each person feel special. Widely described as almost impossible to dislike, Georgiana captured the hearts of almost everyone she met. While the Duchess of Devonshire coped with the marital arrangements on the surface throughout her marriage, she nevertheless suffered emotional and psychological distress. She sought further personal consolation from a "dissipated existence" in passions (socialising, fashion, politics, writing), addictions (gambling, drinking, and drugs), and affairs (with several men, not just Grey, possibly including the bachelor Duke of Dorset). With her renowned unconventional beauty and kind character, alongside her marriage to the affluent and powerful Duke of Devonshire, the Duchess of Devonshire enjoyed preeminence in society. She was a high emblem of the era. Georgiana was arguably the Princess Diana of her time, as her celebrity and her popularity with the press and public can be compared to what her ancestor experienced and became more two hundred years later. Like Diana, Princess of Wales, every move Georgiana made was watched by spies around her and then reported on by the press, her every mistake made mockery of the next day in the papers. On a personal note, Georgiana shared with Diana, Princess of Wales a famously unhappy marriage, a binging eating disorder, a passionate personality, and a mutual love for her children. Like her dear friend Marie Antoinette, the Duchess of Devonshire was one of the fashion icons of her time, and her keen sense made her the leader of fashion in England. Every outfit the Duchess wore, including her hairstyle, was immediately copied by the masses. The fashionable styling of her hair alone reached literally extraordinary heights above her exuberant costumes. Using her influence as a leading socialite and fashion icon, the Duchess of Devonshire contributed to politics, science, and literature. As part of her illustrious social engagements, the Duchess would gather around her a large salon of literary and political figures. Among her major acquaintances were the most influential figures of her time, including the Prince of Wales (later King George IV); Marie Antoinette of France and her favourite in court, the Duchess of Polignac; Charles Grey (later Earl Grey and British Prime Minister); and Lady Melbourne (lover of the Prince of Wales), as well as Samuel Johnson, a famed writer of the era. Newspapers chronicled her every appearance and activity. She was called a "phenomenon" by Horace Walpole who proclaimed, "[she] effaces all without being a beauty; but her youthful figure, flowing good nature, sense and lively modesty, and modest familiarity make her a phenomenon". The Spencer family, from which she derived, was an ardent supporter of the Whig party as were she and the House of Cavendish. However, because the duke's high position in the peerage disallowed him from participating so commonly in politics, the Duchess took it as a positive outlet for herself. In an age when the realisation of women's rights and suffrage were still more than a century away, the duchess became a political activist as the first woman to make active and influential front line appearances on the political scene. She relished Enlightenment and Whig party ideals. Her friend, The Prince of Wales, who always relished going against the grain with his father King George III (who detested the Whigs)joined the Whig party when the the duchess became involved. She was renowned for hosting dinners that became political meetings, and she took joy in cultivating the company of brilliant radicals. During the general election of 1784, the Duchess was instrumental in the success of Whig party, but retired, after the win. In 1788, she returned to political activism though behind the scenes. Even in the last years of her life, she pushed ahead in the field and attempted to help rebuild the Whig party, which had become fragmented; her efforts were to no avail, and the political party would eventually come to dissolve decades after her death. Georgiana composed poetry as a young girl to her father, and some of it later circulated in manuscript. In her life, the Duchess was an avid writer and composed several works, of both prose and poetry, of which some were published. The first of her published literary works was Emma; Or, The Unfortunate Attachment: A Sentimental Novel in 1773. In 1778, the epistolary novel The Sylph was released. Published anonymously, it had autobiographical elements, centering on a fictional aristocratic bride who had been corrupted, and as "a novel-cum-exposé of [the duchess's] aristocratic cohorts, depicted as libertines, blackmailers, and alcoholics." The duchess is said to have at least privately admitted to her authorship. The Sylph was a success and underwent four reprintings. The Passage of the Mountain of Saint Gothard, was first published in an unauthorised version in the 'Morning Chronicle' and 'Morning Post' of 20 and 21 December 1799, then in a privately printed edition in 1800. A poem dedicated to her children, The Passage of the Mountain of Saint Gothard was based on her passage of the Saint Gotthard Pass, with Bess, between 10 and 15 August 1793 on returning to England. The thirty-stanza poem, together with 28 extended notes, were furthermore translated into some of the main languages of Western Europe such as French, Italian, German. English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge published a glowing response to the poem, 'Ode to Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire' in the 'Morning Post' on 24 December 1799. The Duchess had a small laboratory where she conducted chemistry experiments and studied geology, natural history and was most passionate for mineralogy. In pursuit of her interest, she hiked to the summit of Mount Vesuvius to observe and study the active crater and later began the Devonshire Mineral Collection at Chatsworth (the main seat of the dukedom of Devonshire). In addition to her scientific curiosity, the Duchess wanted to contribute to her children's education. She frequently engaged in scientific dialogue with prominent scientists of the era and her knowledge of chemistry and mineralogy was regarded as genius. The Duchess played a key role in formulating, with Thomas Beddoes, the idea of establishing the Pneumatic Institution in Bristol. Her efforts to establish the Pneumatic Institute which advanced the study of factitious airs is an important event that provided framework for modern anesthesia as well as modern biomedical research in gasotransmitters. As was common among the aristocracy of her time, the Duchess routinely gambled for leisure and amusement. Her gaming spiraled into a ruinous addiction, however, made worse by her emotional instability. In the first years of her marriage, she accumulated debts that surpassed the 4,000 pounds that the Duke provided her annually as pin money. The duke found out later and repaid them. For the rest of her life, the Duchess continued to amass an immense, ever-escalating debt that she always tried to keep hidden from her husband (even though he was among the richest men in the land). While she would admit to some amount, it was always less than the total, which even she could not keep up with. In confidence, she would ask for loans from the Prince of Wales. In 1796, the Duchess of Devonshire succumbed to illness in one eye; the medical treatment resulted in a scarring of her face. However, "Those scars released her from her fears. During her early forties, the Duchess of Devonshire devoted her time to the coming out of her eldest daughter, Lady Georgiana Dorothy Cavendish. The debutante was presented in 1800, and the duchess saw her daughter wed Lord Morpeth, the heir apparent of the Earl of Carlisle, in 1801; it was the first and only time the Duchess of Devonshire saw one of her issue marry. Her health continued to decline well into her forties, and her gambling addiction continued. Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, died on 30 March 1806, at 3:30, at the age of 48. She was surrounded by her husband, the 5th Duke of Devonshire; her mother, Countess Spencer; her sister, the Countess of Bessborough; her eldest daughter, Lady Morpeth (who was eight months pregnant); and Lady Elizabeth Foster. They were all said to have been inconsolable over her death. The Prince of Wales himself lamented, "The best natured and the best-bred woman in England is gone." Thousands of the people of London congregated at Piccadilly, where the Cavendish home in the city was located, to mourn her. She was buried at the family vault at All Saints Parish Church (now Derby Cathedral) in Derby. Immediately after her death, the Duke of Devonshire discovered the extent of her debts. He soon enough married Lady Elizabeth Foster, who became Duchess of Devonshire as his second wife. Georgiana's children were discontented with the marriage as they never liked Lady Elizabeth at all. When William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, died on 29 July 1811, the Marquess of Hartington became 6th Duke of Devonshire. He sought to liquidate his late mother's entire debts, and dismissed Lady Elizabeth by paying her off. Over 1,000 personal letters written by the Duchess of Devonshire remain in existence. Chatsworth, the duke of Devonshire's seat, houses a majority of her letters in historical archives. Artwork representing the Duchess of Devonshire by reputable painters of the Georgian era remain, including a 1787 portrait by the famed Thomas Gainsborough which was once thought lost. The legacy of the life of Georgiana Cavendish, 5th Duchess of Devonshire, has remained a topic of study and intrigue in cultural and historical spheres centuries after her death. In 1786, Susanna Rowson, who went on to become a bestselling author, dedicated her first published work, Victoria, to the Duchess of Devonshire. Since early 20th century, many films have been made inspired by Georigiana's story, such as:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|