|

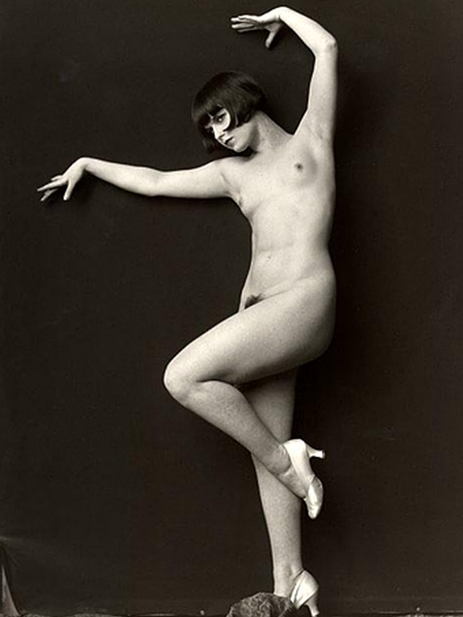

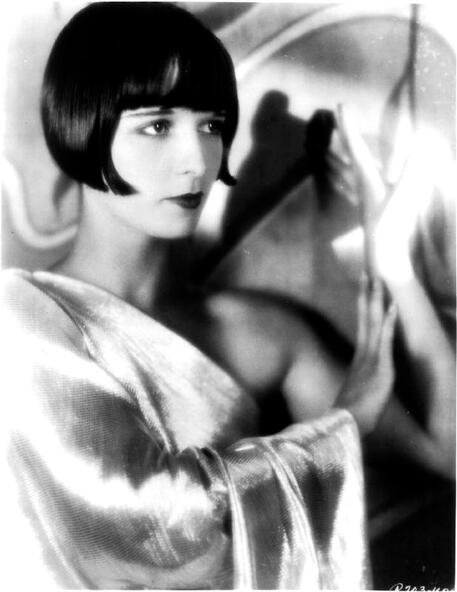

Mary Louise Brooks (November 14, 1906 – August 8, 1985), known professionally as Louise Brooks, was an American film actress and dancer during the 1920s and 1930s. She is regarded today as a Jazz Age icon and as a flapper sex symbol due to her bob hairstyle that she helped popularize during the prime of her career. At the age of fifteen, Brooks began her career as a dancer and toured with the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts. After being fired, she found employment as a semi-nude dancer in the Ziegfeld Follies in New York City. While dancing in the Follies, Brooks came to the attention of Walter Wanger, a producer at Paramount Pictures, and was signed to a five-year contract with the studio. She appeared in supporting roles in various Paramount films before taking the heroine's role in Beggars of Life (1928). During this time, she became an intimate friend of actress Marion Davies and joined the elite social circle of press baron William Randolph Hearst at Hearst Castle in San Simeon. Dissatisfied with her mediocre roles in Hollywood films, Brooks went to Germany in 1929 and starred in three feature films which launched her to international stardom: Pandora's Box (1929), Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), and Miss Europe (1930). By 1938, she had starred in seventeen silent films and eight sound films. After retiring from acting, she fell upon financial hardship and became a paid escort. For the next two decades, she struggled with alcoholism and suicidal tendencies. Following the rediscovery of her films by cinephiles in the 1950s, a reclusive Brooks began writing articles about her film career; her insightful essays drew considerable acclaim. She published her memoir, Lulu in Hollywood, in 1982. Three years later, she died of a heart attack at age 78. BiographyBorn in Cherryvale, Kansas, Louise Brooks was the daughter of Leonard Porter Brooks, a lawyer and Myra Rude, a talented pianist who played the latest Debussy and Ravel for her children, inspiring them with a love of books and music. Brooks described the hometown of her childhood as a typical Midwestern community where the inhabitants "prayed in the parlor and practiced incest in the barn." When Louise was nine years old, a neighborhood man sexually abused her. Beyond the physical trauma at the time, the event continued to have damaging psychological effects on her personal life as an adult and on her career. That early abuse caused her later to acknowledge that she was incapable of real love. Brooks began her entertainment career as a dancer, joining the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts modern dance company in Los Angeles at the age of 15 in 1922. The company included founders Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, as well as a young Martha Graham. However, a long-simmering personal conflict between Brooks and St. Denis boiled over one day, and St. Denis abruptly fired Brooks from the troupe in the spring of 1924. Brooks was 17 years old at the time of her dismissal. She soon worked as a semi-nude dancer in the 1925 edition of the Ziegfeld Follies. That same year she sued the New York glamour photographer John de Mirjian to prevent publication of his risque studio portraits of her; the lawsuit made him notorious. As a result of her work in the Follies, Brooks came to the attention of Walter Wanger, a producer at Paramount Pictures. An infatuated Wanger signed her to a five-year contract with the studio in 1925. Soon after, Brooks met movie star Charlie Chaplin with whom she had a two-month affair while Chaplin was married to Lita Grey. When their affair ended, Chaplin sent her a check. Brooks made her screen debut in the silent The Street of Forgotten Men, in an uncredited role in 1925. Soon, however, she was playing the female lead in a number of silent light comedies and flapper films over the next few years. In the summer of 1926, Brooks married Eddie Sutherland, the director of the film she made with W. C. Fields, but by 1927 had become infatuated with George Preston Marshall, owner of a chain of laundries and future owner of the Washington Redskins football team, following a chance meeting with him that she later referred to as "the most fateful encounter of my life". She divorced Sutherland, mainly due to her budding relationship with Marshall, in June 1928. Sutherland was purportedly extremely distraught when Brooks divorced him and, on the first night after their separation, he attempted to take his life with an overdose of sleeping pills. Throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, Brooks continued her on-again, off-again relationship with George Preston Marshall which she later described as abusive. By the late1920s, she was socializing with wealthy and famous persons. She was a frequent house guest of the media magnate William Randolph Hearst and his mistress Marion Davies(who also used to be a Ziegfeld Follies girl ) at Hearst Castle in San Simeon. Brooks gained a cult following in Europe for her pivotal vamp role in the 1928 Howard Hawks silent buddy film A Girl in Every Port. Her distinctive bob haircut helped start a trend, and many women styled their hair the same way. She refused to stay on at Paramount after being denied a promised raise. Her friend and lover George Preston Marshall suggested that she travel to Europe to make films with the prominent Austrian Expressionist director G.W. Pabst. On the last day of filming The Canary Murder Case Brooks departed Paramount Pictures to leave Hollywood for Berlin. Brooks traveled to Europe accompanied by her paramour George Preston Marshall and his English valet. The German film industry was Hollywood's only major rival at the time, and the film industry based in Berlin was known as the Filmwelt ("film world") reflecting its own self-image as a highly glamorous "exclusive club". After their arrival in Weimar Germany, she starred in the 1929 silent film Pandora's Box, directed by Pabst in his New Objectivity period. Pabst was one of the leading directors of the filmwelt, known for his refined, elegant films that represented the filmwelt "...at the height of its creative powers". The film Pandora's Box is notable for its frank treatment of modern sexual mores, including one of the first overt on-screen portrayals of a lesbian. Brooks' performance in Pandora's Box made her into a star. In looking for the right actress to play Lulu, the central figure of the film, Pabst had rejected Marlene Dietrich as "too old" and too obvious." Dissatisfied with Europe, Brooks returned to New York in December 1929. When Brooks returned to Hollywood in 1931, she was cast in two mainstream films, God's Gift to Women (1931) and It Pays to Advertise (1931), but her performances in these films were largely ignored by critics, and few other job offers were forthcoming. After being offered of a $500 per week salary from Columbia Pictures, She returned to Hollywood, but after refusing to do a screen test for a Western film, the contract offer was withdrawn. Brooks declared bankruptcy in 1932, and she began dancing in nightclubs to earn a living. In 1933, she married Chicago millionaire Deering Davis, a son of Nathan Smith Davis Jr., but abruptly left him in March 1934 after only five months of marriage, "without a good-bye... and leaving only a note of her intentions" behind her. The couple officially divorced in 1938. She attempted a film comeback in 1936 and did a bit part in Empty Saddles, a Western that led Columbia to offer her a screen test. In 1937, Brooks managed to obtain a bit part in the film King of Gamblers. Unfortunately, after filming, Brooks' scenes were deleted. Brooks made two more films after that, including the 1938 Western Overland Stage Raiders in which she plays the romantic lead, opposite John Wayne, with a long hairstyle that renders her all but unrecognizable from her Lulu days. Brooks' career prospects as a film actress had significantly declined by 1940. According to the federal census in May that year, she was living in a $55-a-month apartment in West Hollywood and was working as a copywriter for a magazine. Soon, however, she found herself unemployed and increasingly desperate for a steady income. Her longtime friend Paramount executive Walter Wanger warned her that she would likely "become a call girl" if she remained in Hollywood. Upon hearing Wanger's warning, Brooks purportedly also remembered Pabst's earlier predictions about the dire circumstances to which she would be driven if her career stalled in Hollywood: "I heard his [Pabst's] words again — hissing back to me. And listening this time, I packed my trunks and went home to Kansas." Heeding Wanger's warning, Brooks briefly returned to Wichita, where she was raised, but this undesired return "turned out to be another kind of hell.". After an unsuccessful attempt at operating a dance studio, she returned to New York City. Following brief stints there as a radio actor in soap operas and a gossip columnist, she worked as a salesgirl in a Saks Fifth Avenue store in Manhattan. Between 1948 and 1953, Brooks embarked upon a career as a courtesan with a few select wealthy men as clients. As her finances eroded, an impoverished Brooks began working regularly for an escort agency in New York. She spent subsequent years "drinking and escorting" while subsisting in obscurity and poverty in a small New York apartment. By this time, "all of her rich and famous friends had forgotten her." as forseen by Pabst, with perhaps the exception of William S. Paley, the founder of CBS who was one of her paramours from years before. Paley provided a small monthly stipend to Brooks for the remainder of her life, and this stipend kept her from committing suicide at one point. Angered by this ostracization, she attempted to write a tell-all memoir titled Naked on My Goat, a title drawn from Goethe's epic play, Faust. After working on that autobiography for years, she destroyed the entire manuscript by throwing it into an incinerator. As time passed, she increasingly drank more and continued to suffer from suicidal tendencies. In 1955, French film historians such as Henri Langlois rediscovered Brooks' films, proclaiming her an unparalleled actress who surpassed even Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo as a film icon. This rediscovery led to a Louise Brooks film festival in 1957 and rehabilitated her reputation in her home country. During this time, James Card, the film curator for the George Eastman House, discovered Brooks "living as a recluse" in New York City. He persuaded her in 1956 to move to Rochester, New York, to be near the George Eastman House film collection where she could study cinema and write about her past career. With Card's assistance, she became a noted film writer. Although Brooks had been a heavy drinker since the age of 14, she remained relatively sober to begin writing perceptive essays on cinema in film magazines, which became her second career. A collection of her writings, titled Lulu in Hollywood, published in 1982 and still in print, was heralded by film critic Roger Ebert as "one of the few film books that can be called indispensable." In the 1970s, she was interviewed extensively on film for the documentaries Memories of Berlin: The Twilight of Weimar Culture (1976), and Hollywood (1980), by Brownlow and David Gill. Lulu in Berlin (1984) is another rare filmed interview, released a year before her death. On August 8, 1985, after suffering from arthritis and emphysema for many years, Brooks died of a heart attack in her apartment in Rochester, New York. She had no survivors and was buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Rochester. After the filming of Pandora's Box concluded, Pabst cast Brooks again in his controversial social drama Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), based on the book by Margarete Böhme.

On the final day of shooting Diary of a Lost Girl, Pabst counseled Brooks not to return to Hollywood and stay in Germany to continue her career as a serious actress. Pabst expressed concern that Brooks' carefree approach towards her career would end in dire poverty "exactly like Lulu's". He further cautioned Brooks that her then-paramour George Marshall and her "rich American friends" would likely shun her when her career stalled. Her appearances in Pabst's two films made Brooks an international star. In an interview published in the February 1930 issue of the American monthly Motion Picture.The Austrian director said: 'Louise has a European soul. You can't get away from it. When she described Hollywood to me—I have never been there—I cry out against the absurd fate that ever put her there at all. She belongs to Europe and to Europeans. She has been a sensational hit in her German pictures. I do not have her play silly little cuties. She plays real women, and plays them marvelously." After the success of her German films, Brooks appeared in one more European film entitled Miss Europe (1930), a French film by Italian director Augusto Genina.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|