|

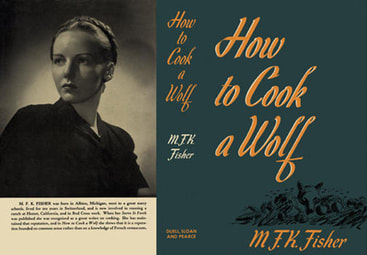

Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher (July 3, 1908 – June 22, 1992) was an American food writer. She was a founder of the Napa Valley Wine Library. Over her lifetime she wrote 27 books, including a translation of The Physiology of Taste by Brillat-Savarin. Fisher believed that eating well was just one of the "arts of life" and explored this in her writing. W. H. Auden once remarked, "I do not know of anyone in the United States who writes better prose." BiographyFisher was born Mary Frances Kennedy on July 3, 1908, at 202 Irwin Avenue, Albion, Michigan. Rex was a co-owner (with his brother Walter) and editor of the Albion Evening Recorder newspaper. In 1919, her father Rex purchased a large white house outside the city limits on South Painter Avenue. The house sat on thirteen acres, with an orange grove; it was referred to by the family as "The Ranch." Although Whittier was primarily a Quaker community at that time, Mary Frances was brought up within the Episcopal Church. Mary enjoyed reading as a child, and began writing poetry at the age of five. The Kennedys had a vast home library, and her mother provided her access to many other books. Later, her father used her as stringer on his paper, and she would draft as many as fifteen stories a day. Mary received a formal education; however, she was an indifferent student who often skipped classes throughout her academic career. She attended Illinois College, but left after only one semester. In 1928, she enrolled in summer school at UCLA in order to obtain enough credits to transfer to Occidental College. While there, she met her future first husband: Alfred Fisher ("Al"). She attended Occidental College for one year then married Al on September 5, 1929, and moved with him to Dijon, France. Food became an early passion in her life. An early food influence was "Aunt" Gwen. Aunt Gwen was not family, but the daughter of friends — the Nettleship family. Mary recalled cooking outdoors with Gwen: steaming mussels on fresh seaweed over hot coals; catching and frying rock bass; skinning and cooking eel; and, making fried egg sandwiches to carry on hikes. Mary wrote of her meals with Gwen and Gwen's brothers: "I decided at the age of nine that one of the best ways to grow up is to eat and talk quietly with good people." Mary liked to cook meals in the kitchen at home, and "easily fell into the role of the cook's helper." In September 1929, newlyweds Mary and Al sailed on the RMS Berengaria to Cherbourg (now Cherbourg-Octeville), France. They traveled to Paris for a brief stay, before continuing south to Dijon. Al attended the Faculté des Lettres at the University of Dijon where he was working on his doctorate; when not in class, he worked on his epic poem, The Ghosts in the Underblows. The poem was based on the Bible and was analogous to James Joyce's Ulysses. Mary attended night classes at the École des Beaux-Arts where she spent three years studying painting and sculpture. They lodged at 14 Rue du Petit-Potet in a home owned by the Ollangnier family. The Ollangniers served good food at home, although Madame Ollangnier was "extremely penurious and stingy." Mary remembered big salads made at the table, deep-fried Jerusalem artichokes, and "reject cheese" that was always good. To celebrate their three-month anniversary, Al and Mary went to the Aux Trois Faisans restaurant — their first of many visits. There, Mary received her education in fine wine from a sommelier named Charles. The Fishers visited all the restaurants in town, where in Mary's words: We ate terrines of pate ten years old under their tight crusts of mildewed fat. We tied napkins under our chins and splashed in great odorous bowls of ecrevisses a la nage. We addled our palates with snipes hung so long they fell from their hooks, to be roasted then on cushions of toast softened with the paste of their rotted innards and fine brandy. By 1931, Fisher had finished the first twelve books of the poem, which he ultimately expected to contain sixty books. That year, Mary and Al moved to their own apartment, above a pastry shop at 26 Rue Monge. It was Mary's first kitchen. It was only five feet by three feet and contained a two-burner hotplate. Despite the kitchen's limitations, or perhaps because of it, Mary began developing her own personal cuisine, with the goal of "cooking meals that would 'shake [her guests] from their routines, not only of meat-potatoes-gravy, but of thought, of behavior.'" In The Gastronomical Me she describes one such meal: There in Dijon, the cauliflowers were very small and succulent, grown in that ancient soil. I separated the flowerlets and dropped them in boiling water for just a few minutes. Then I drained them and put them in a wide shallow casserole, and covered them with heavy cream, and a thick sprinkling of freshly grated Gruyere, the nice rubbery kind that didn't come from Switzerland at all, but from the Jura. It was called râpé in the market, and was grated while you watched, in a soft cloudy pile, onto your piece of paper. After Al was awarded his doctorate, they moved briefly to Strasbourg, France, then a tiny French fishing village, Le Cros-de-Cagnes. Al had stopped work on his poem, was trying to write novels and did not want to return to the States. After running out of funds, the Fishers returned to California, sailing on the Feltre out of Marseilles. Back in California, Al and Mary initially moved in with Mary's family at "The Ranch" and later moved into the Laguna cabin. Al spent two years looking for a teaching position until he found one at Occidental College. Mary began writing and she published her first piece — "Pacific Village" — in the February 1935 issue of Westways magazine. The article was a fictional account of life in Laguna Beach Mary worked part-time in a card shop and researched old cookery books at the Los Angeles Public Library. She began writing short pieces on gastronomy. The pieces were later to become her first book: Serve It Forth. Mary next began work on a novel she never finished; it was based on the founding of Whittier. During this period, Mary's marriage with Al was beginning to fail. In 1933, Dillwyn Parrish and his wife Gigi moved next door to them, and they rapidly became friends. After Parrish divorced Gigi in 1934, Mary found herself falling in love with him. In Mary's words, she one day sat next to Parrish at the piano and told him she loved him. In 1935, with Al's permission, Mary traveled to Europe with Parrish and his mother. The Parrishes had money, and they sailed on the luxury liner Hansa. Mary revisited Dijon and ate with Parrish at Aux Trois Faisans where she was recognized and served by her old friend, the waiter Charles. She later wrote a piece on their visit — "The Standing and the Waiting" — which was to become the centerpiece of Serve It Forth. Upon her return from Europe, Mary informed Al of her developing relationship with Parrish. In 1936, Dillwyn invited the Fishers to join him in creating an artists' colony at Le Paquis — a two-story stone house that Parrish had bought with his sister north of Vevey, Switzerland. Notwithstanding the clear threat to his marriage, Al agreed. "Le Paquis" means the grazing ground. The house sat on a sloping meadow on the north shore of Lake Geneva, looking across to the snowcapped Alps. They had a large garden in which "We grew beautiful salads, a dozen different kinds, and several herbs. There were shallots and onion and garlic, and I braided them into long silky ropes and hung them over rafters in the attic." In mid-1937 Al and Mary separated. He returned to the States where he began a distinguished career as a teacher and poet at Smith College. In 1938, Mary returned home briefly to inform her parents in person of her separation and pending divorce from Al. Meanwhile, her first book, Serve It Forth, had opened to largely glowing reviews, including reviews in Harper's Monthly, The New York Times and the Chicago Tribune. Mary, however, was disappointed in the book's meager sales because she needed the money. During this same period, Mary and Parrish also co-wrote (alternating chapters) a light romance entitled Touch and Go under the pseudonym Victoria Berne. The book was published by Harper and Brothers in 1939. In September 1938, Mary and Parrish could no longer afford to live at Les Paquis and they moved to Bern, where Parrish underwent two surgeries but could not get a good diagnosis from his doctors. With the onset of World War II, and Parrish's need for medical care, Mary and Parrish returned to the States, where he ultimately was diagnosed as having Buerger's disease (Thromboangiitis obliterans) — a circulatory system malady that causes extreme thrombosis of the arteries and veins, causing severe pain, and often necessitating multiple amputations. The disease is progressive and there was (and is) no known successful treatment. They returned briefly to Switzerland to close down their apartment, and returned to California. Once in California, Mary searched for a warm dry climate that would be beneficial for Parrish's health. She found a small cabin on ninety acres of land south of Hemet, California. They bought the property and named it "Bareacres" after the character Lord Bareacres in Vanity Fair by Thackeray. Lord Bareacres was land-poor; his only asset was his estate. Although Parrish's life at Bareacres had its ups and downs, its course was a downward spiral. Ultimately, Parrish could no longer tolerate the pain and the probable need for additional amputations. On the morning of August 6, 1941, Mary was awakened by a gunshot. Venturing outside, she discovered that Parrish had committed suicide. Mary later would write, "I have never understood some (a lot of) taboos and it seems silly to me to make suicide one of them in our social life." During the period leading up to Tim's death (Parrish was often called "Tim" by family and friends, but referred to as "Chexbres" in Fisher's autobiographical books), Mary completed three books. The first was a novel entitled The Theoretical Foot. It was a fictional account of expatriates enjoying a summer romp when the protagonist, suffering great pain, ends up losing a leg. The second book was an unsuccessful attempt by her to revise a novel written by Tim, Daniel Among the Women. Third, she completed and published Consider the Oyster, which she dedicated to Tim. The book was humorous and informative. It contained numerous recipes incorporating oysters, mixed with musings on the history of the oyster, oyster cuisine, and the love life of the oyster. In 1942, Mary published How to Cook a Wolf. The book was published at the height of WWII food shortages. In May 1942 Mary began working in Hollywood for Paramount Studios. While there she wrote gags for Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Dorothy Lamour. Mary became pregnant in 1943, and secluded herself in a boarding house in Altadena. While there she worked on the book that would become The Gastronomical Me. On August 15, 1943, she gave birth to Anne Kennedy Parrish (later known as Anna). Mary listed a fictional father on the birth certificate, Michael Parrish. She never revealed the father's identity. In 1944, Mary broke her contract with Paramount. On a trip to New York, she met and fell in love with publisher Donald Friede. She spent the summer in Greenwich Village with Friede, working on the book that would become Let Us Feast. Her relationship with Friede gave her entree to additional publishing markets, and she wrote articles for Atlantic Monthly, Vogue, Town and Country, Today's Woman and Gourmet. In fall 1945, Friede's publishing entity failed, and Mary and Donald returned to Bareacres, both to write. On March 12, 1946, Mary gave birth to her second daughter, Kennedy Mary Friede. Mary began work on With Bold Knife and Fork. Mary's mother died in 1948. In 1949, she moved to the Ranch to take care of her father, Rex. On Christmas Eve 1949, the limited edition release of her translation of Savarin's The Physiology of Taste received rave reviews. During this period, Mary also was working on a biography of Madame Récamier for which she had received an advance. Her marriage with Donald was starting to unravel. He became ill with intestinal pains and after considerable medical treatment, it became apparent that the pain was psychosomatic, and Don began receiving psychiatric care. Mary in turn had been under considerable stress. She had been caretaker for Tim, had weathered his suicide, suffered her brother's suicide a year later, followed by the death of her mother, only to be thrust into the role of caretaker for Rex. Despite her financially successful writing career, Don lived a lifestyle that exceeded their income, leaving her $27,000 in debt. She sought psychiatric counseling for what essentially was a nervous breakdown. By 1949, Donald had become frustrated by his isolation in a small Southern California town and separated from Mary. They divorced on August 8, 1950. Her father died June 2, 1953. Mary subsequently sold the Ranch and the newspaper. She rented out Bareacres and moved to Napa Valley, renting "Red Cottage" south of St. Helena, California. Dissatisfied with the educational opportunities available to her children, Mary sailed to France in 1954. She ended up in Aix-en-Provence, France. She planned to live in Aix using the proceeds from the sale of her father's paper. Once in Aix, Mary employed a French tutor and enrolled Anna and Kennedy, then aged 11 and 8, in the École St Catherine. In Aix, her life developed a pattern. Each day she would walk across town to pick up the girls from school at noon, and in late afternoon they ate snacks or ices at the Deux Garçons or Glacière, but she never felt completely at home. Mary left Provence in July 1955, and sailed for San Francisco on the freighter Vesuvio. After living in the city for a short period, she decided that the intense urban environment did not provide the children enough freedom. She sold Bareacres and used the proceeds to buy an old Victorian house on Oak Street in St. Helena. She owned the house until 1970, using it as a base for frequent travels. During extended absences she would rent it out. In fall 1959 she moved the family to Lugano, Switzerland, where she hoped to introduce her daughters to a new language and culture. She revisited Dijon and Aix. Falling back in love with Aix, she rented the L'Harmas farmhouse outside Aix.

In July 1961, she returned to San Francisco. She contracted to write a series of cookbook reviews for The New Yorker magazine. In 1966, Time-Life hired Mary to write The Cooking of Provincial France. She traveled to Paris to research material for the book. While there, she met Paul and Julia Child, and through them James Beard. Child was hired to be a consultant on the book; Michael Field was the consulting editor. Fisher was disappointed in the book's final form; it contained restaurant recipes, without regard to regional cuisine, and much of her signature prose had been cut. In 1971, Mary's friend David Bouverie, who owned a ranch in Glen Ellen, California, offered to build Mary a house on his ranch. Mary designed it, calling it "Last House". And she spent the last twenty years of her life in "Last House". After Dillwyn Parrish's death, Fisher considered herself a "ghost" of a person, but she continued to have a long and productive life, while suffering from Parkinson's disease and arthritis. M.F.K. Fisher died at the age of 83 in Glen Ellen, California, in 1992.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

December 2023

|